William Styron, the acclaimed novelist and leading literary figure of his generation whose summer home on the Vineyard Haven harbor has long been the hub of the area known colloquially as writer's row, died Wednesday at the Martha's Vineyard Hospital. He was 81.

The cause of death was pneumonia. Mr. Styron had been in failing health for a number of years.

Often called the heir to William Faulkner (although he rejected the characterization), Mr. Styron was originally from the South, and he won critical acclaim early on for his first novel, Lie Down in Darkness. A brooding meditation on a young girl's suicide, the book was published in 1951 when Mr. Styron was 26. In 1955 he published The Long March, originally a novella about his experiences in the U.S. Marine Corps. In 1954, after a year in Italy, he published his second novel, Set This House on Fire, a portrait of a group of Americans in Italy.

The Confessions of Nat Turner followed in 1967, a fictional account of a real rebellion led by the slave Nat Turner in 1831. The violent rebellion took place near where Mr. Styron had grown up in Virginia. In 1968 it won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction and in 1970 it captured the William Dean Howells Medal of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. His other works that earned acclaim included Sophie's Choice (1979), the story of a fictional Polish Catholic woman who survives internment at Auschwitz, later made into a major motion picture, and Darkness Visible: A Memoir of Madness (1990), a chronicle of his depression in 1985.

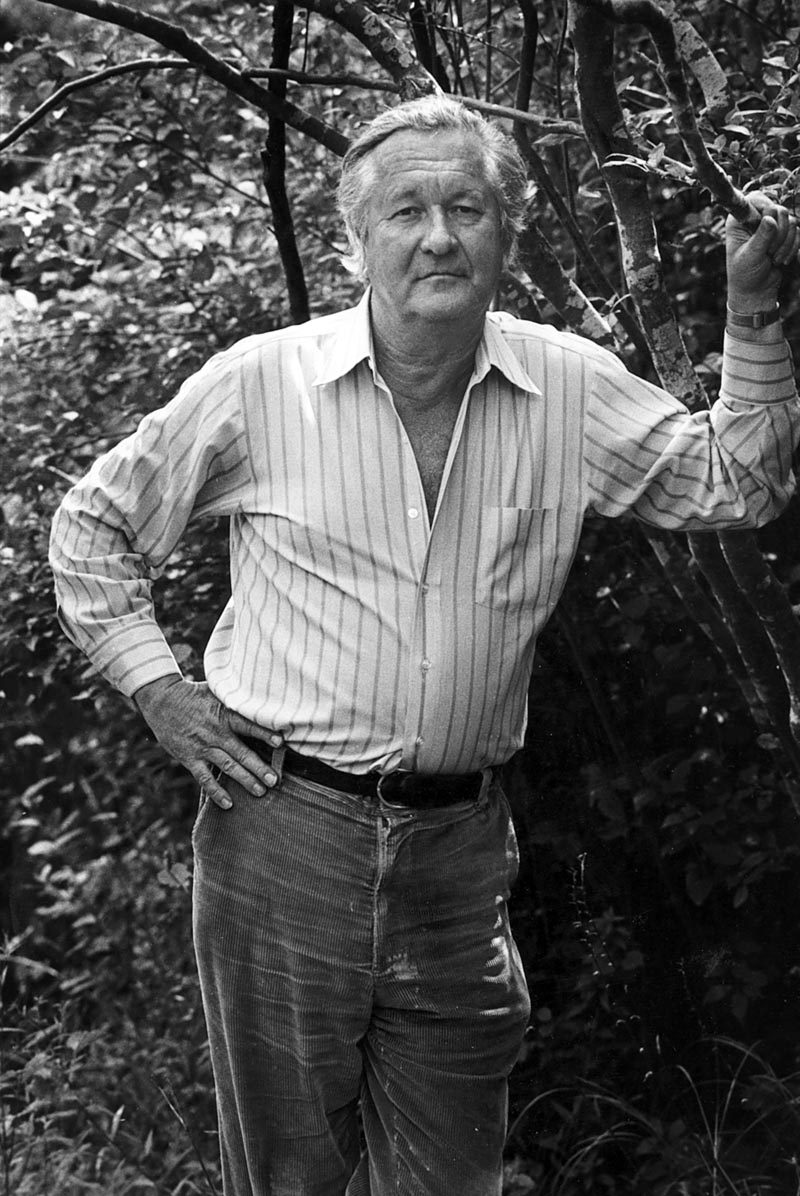

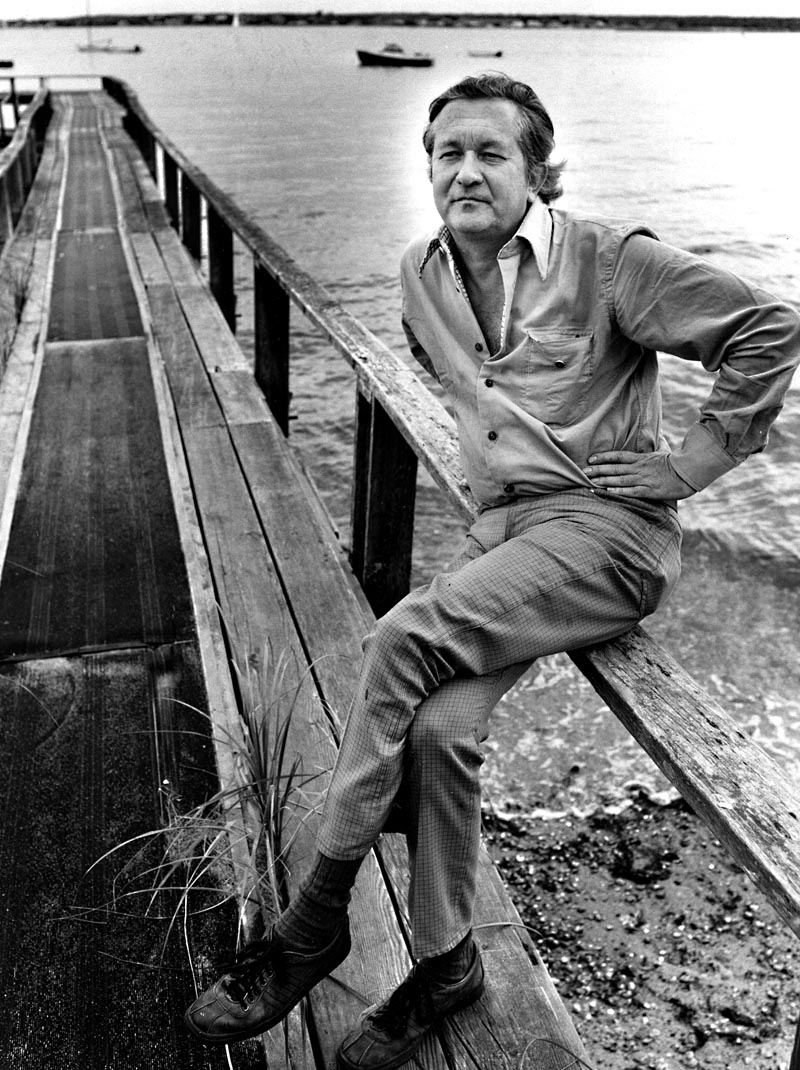

Unconventional in routine, tall and handsome with a piercing gaze, relaxed in his family and social life, Mr. Styron was one of the rare authors who was both a literary and commercial success. He had lived on the Vineyard seasonally since 1959, and his contributions to the Island were also largely literary. He spoke at library lecture series and wrote graceful book reviews, including a review that was published in the Gazette in 1991 of the memoir Deadline, by New York Times columnist James Reston.

In 1982 he told a reporter for the Gazette that he found the Vineyard a good place to work, a place where he liked to walk for miles and think. Asked how he got anything done in the summer, he showed a brief glimpse of his characteristic macabre humor.

"I hear the bump of the tennis balls," he said. "I hear the sails luffing in the harbor and I take a perverse delight in eschewing all those wonderful pleasures and hunkering down in my damp little mildewed studio in Vineyard Haven and saying, ‘I'm doing my work while they're playing.'"

He wrote in longhand on yellow legal pads, never kept a notebook and read voraciously. He liked to sleep until noon, putter at errands and daydream before settling down to work each day. On the Vineyard he wrote on an old school desk that he bought in Vineyard Haven for $15 in 1965, soon after buying his summer home. He drank heavily and smoked cigars until the summer of his 60th birthday in 1985, when he decided that alcohol no longer agreed with him and gave it up. But the abstinence triggered mood disorders which required medication, and the drugs in turn brought on a deep, enduring and suicidal depression that required him to be hospitalized for more than two months.

The experience prompted him to write Darkness Visible: a Memoir of Madness, after he had recovered.

The book earned Mr. Styron a whole new set of followers. "I think it causes people to realize two things," he told the Gazette in an interview in 2001. "That this is a pain that afflicts a lot of people; it's universal and if I could describe it in this way and people could relate to it, it meant they weren't alone; and the second thing - almost as important or more important - is stressing the truth that people can get well, and that it's not by any means fatal."

Depression continued to stalk him for the remainder of his life.

William Clark Styron Jr. was born on June 11, 1925 in Newport News, Va.; his father was a marine engineer. He had a happy childhood, was an early reader and was socially outgoing. His mother, Pauline Margaret (Abraham) Styron, died when he was 13. He later acknowledged her death as a cause of the depression that gripped him for more than two decades.

In 1940 his father sent him to Christchurch, a small Episcopal preparatory school in West Point, Va., for his last two years of high school. He graduated in 1942. Following high school he joined the reserve officer training program for the United States Marine Corps, and enrolled at Davidson College. He was unhappy there and through the Marines transferred to Duke University in June of 1943. In October of 1944 he was called to active duty and in late July 1945 was commissioned a second lieutenant. He was assigned to participate in the invasion of Japan; a month later the atomic bomb attacks forced the surrender of Japan and he was discharged.

He returned to Duke University where he was influenced and guided by his friend and writing mentor Prof. William Blackburn. Mr. Styron graduated in 1947, determined to become a novelist.

He moved to New York city, and after finishing Lie Down in Darkness, did another three-month stint in the Marines. Then Lie Down in Darkness won the Prix de Rome, which meant a year's paid expenses at the American Academy in Rome. During his year in Rome he became reacquainted with Rose Burgunder, whom he had met in Baltimore the year before and who was enrolled at the American Academy.

They were married in Rome in May of 1953, and had three daughters and one son.

The Styrons raised their family in a farmhouse in Roxbury, Conn., and spent their summers on the Vineyard, where their many friends included the Buchwalds, the Herseys, the Wallaces, the Hackneys, Lillian Hellman, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, Katharine Graham and the Clintons. The Styron home became a well-known setting for social gatherings large and small, with cocktails and fried chicken on the porch overlooking the outer harbor in the Island's main port town. At one such gathering in 1959, Mr. Styron told a Gazette reporter that he had given up television and also The New Yorker. "It seems to me that J.D. Salinger is about the only writer The New Yorker has who is allowed to write just as he wants to," he said.

Mr. Styron was an active Democrat and was involved in many political causes over the years. He felt it was a natural outgrowth for a writer and commented more than once on the power of art and writing as forces for political change. "Corrupt governments are terrified of the artist's power to expose what's wrong in society," he told the Martha's Vineyard Magazine in a 1989 interview. He also said: "Men of power in the United States have almost never given a shake for writing. I think it is accurate to say that George Bush has probably never read a book in the last four or five years."

He is survived by his wife Rose and daughters Alexandra Styron of Brooklyn, N.Y., Susanna Styron of Nyak, N.Y., and Paola Styron of Sherman, Conn; a son, Thomas Styron of New Haven, Conn., and eight grandchildren.

The funeral service is private, and memorial services will be held on the Island and in New York at a later date.

Donations may be made in his memory to the Martha's Vineyard Hospital Building Fund, P.O. Box 1477, Oak Bluffs, MA, 02557. Arrangements are under the care of Chapman, Cole and Gleason Funeral Home in Oak Bluffs.

Comments

Comment policy »