The disclaimer found at the front of political novels is generally trivial boilerplate. It implies that the novelist, or his publisher at least, is a bit chicken. Coy allusions to real people and events may be made but vaguely and behind the blast wall of imagination.

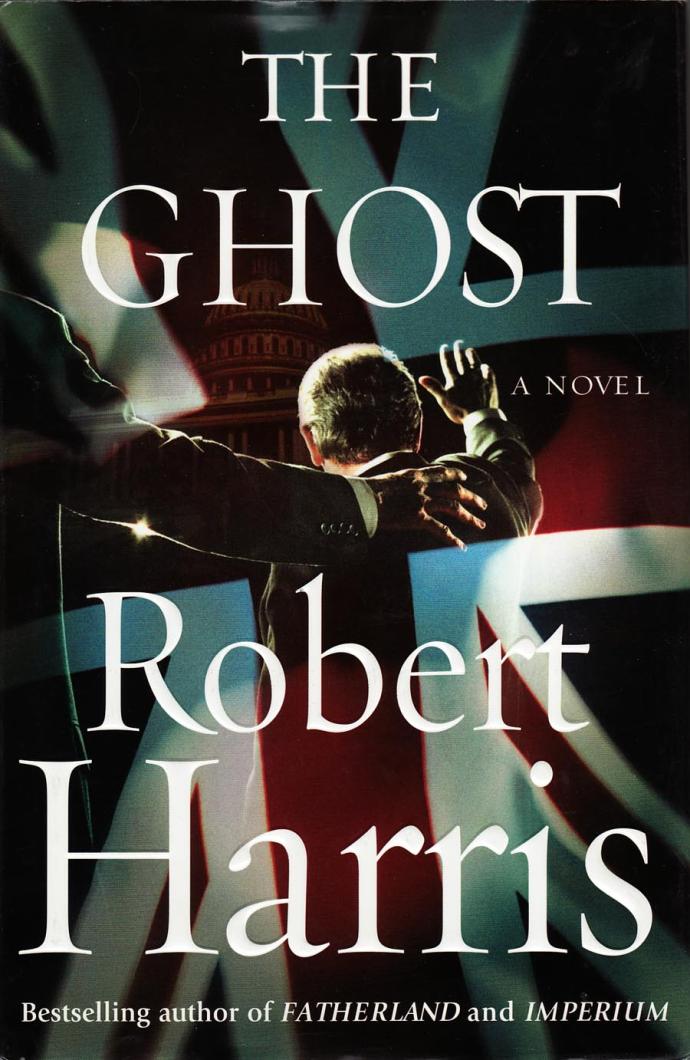

Robert Harris’s latest book, The Ghost, announces itself as “a work of fiction.” But as the story of an ex-British prime minister holed up in a rented West Tisbury mansion with a ghostwriter who is attempting to pen his memoir, it has received much attention in the U.K. from those conjecturing about just how closely it sticks to the reality of Tony Blair and his entourage.

And considering what Mr. Harris then implicates his characters in — murder, multiple affairs, collusion in state-organised torture, a global secret service conspiracy — the short caveat at the beginning of his book is probably a good idea.

The U.K. novelist and political journalist knocked out this political thriller in under a year — putting aside Imperium, his on-going trilogy based on the life of Cicero, for a rare foray into the present. The idea had been germinating in the author’s mind since the early ’90s; Mr. Harris felt that at the end of last year, with Britain’s prime minister Blair on his way out, the time was right.

“I had the idea of a prime minister whose glittering career has ended,” he says, via telephone from his home in Berkshire, U.K. “In one sense I wanted to remind myself I could do it.

“I was really happy to be writing about people who weren’t wearing togas. Plus, the physical research was much lighter.”

Much of this research was conducted on the Island the weekend after Thanksgiving last year, with the help of poet and Vineyarder Rose Styron. Mr. Harris was put in touch with Mrs. Styron through his New York literary agent, who also had represented her late husband, author William Styron, and is Mrs. Styron’s godson.

Mr. Harris’s narrator is a ghostwriter hired to write the memoirs of the (fictional) British prime minister Adam Lang. The narrator is brought in to replace another ghostwriter, the luckless Michael McAra, who plummeted into an icy grave from the Woods Hole ferry. As the action unfolds, Harris’s narrator begins to suspect that McAra was the victim of foul play, which is what begins his increasingly murky trail towards the truth. He suspects the original ghostwriter knew too much. By this time the narrator is in deep himself.

Rose Styron has just finished reading The Ghost and has a theory about the Michael McAra character.

“I had the whole afternoon planned out,” she remembers of Harris’s visit. “We were going around to Seven Gates and then on for a walk at The Trustees of Reservations.”

As they sat down for lunch, though, Mr. Harris had just one question. “Where’s McNamara’s house?”

That’s Robert McNamara, U.S. secretary of defense from 1961 to 1968 and an architect of the Vietnam War, who has a seasonal house in Chilmark.

One evening in September 1972, a Vineyard artist who was against the war reportedly spotted Mr. McNamara on the ferry and lured him onto the deck. When McNamara leaned against the railing the artist grabbed him and hoisted him over the railings. Mr. McNamara held on to the side of the boat long enough for someone to notice the struggle and pull his assailant off. Vineyard Haven police were alerted and waiting for the ferry when it docked, but the assailant had been helped off the back of the boat by a friend on the crew. In any case, Mr. McNamara declined to press the charges.

Mrs. Styron spotted the name simliarity to Harris’ character — McAra, McNamara — and detected a nod to the politician.

Mr. Harris does not confirm this specific connection but states that the political aura of Martha’s Vineyard was a deciding factor in the choice of venue. “And McNamara actually makes a cameo appearance. The old man whose house the narrator knocks on says, ‘I was working at the world bank and they tried to throw me off the ferry.’ No one’s noticed yet. I hope he won’t mind.”

Beyond McNamara, the Island is poltically resonant, Mr. Harris feels. “I was originally going to set it in Vermont because of Alexandr Solzhenitsyn, who was there in exile, like my prime minister character. But my editor at Simon & Schuster suggested Martha’s Vineyard because of the connections with the Kennedys and Clinton, and their connection to New Labor.”

Mr. Harris stuck to the facts, and got the most out of his trip material-wise, down to the satellite navigation system that was in his rental car in Boston, a device which formed the central part of a main action sequence in the novel. He stayed in the Harbor View Hotel in Edgartown; a thinly-veiled version of Edgartown’s stately old hotel is where the narrator spends his first nights on the Island.

The mid-November Vineyard Mr. Harris depicts is a ghost-island and a depressing sketch of a resort off-season. Our vegatation gets a particularly unfavorable write-up: “In winter I doubt if nature has a more depressing vista to offer that mile after mile of those twisted, dwarfish ash-colored trees,” says his narrator at one point. A trip through West Tisbury’s back roads this week will tell you that this is not a stretch, but Mr. Harris is quick to underscore that this is the narrator’s impression, not his — “I love Martha’s Vineyard,” he maintains.

“But I wanted a feeling of melancholy,” he says. “This character has ended a glittering career, and I wanted the impression of desolation.”

On his tour Mrs. Styron drove him past a house on Oyster Watcha Road and he knew he had found a setting that met these requirements.

“He said ‘You have to get me in there,’” says Mrs. Styron, who knows the owner. The search took her as far as South Africa, but she made contact and the next morning was able to introduce Mr. Harris to caretakers of the property who took the author on a tour. Mrs. Styron says the resultant portrait of the holiday house off-season is accurate.

“When he wrote about the protestors at the end of the West Tisbury Road though, I laughed,” says Mrs. Styron. She looks out from her bright white front room to the Vineyard Haven sound and reasons, “That would never happen here.”

In the book a raucous gaggle of Iraq War protestors keep vigil outside the ex-British prime minister’s West Tisbury residence, when a story begins to break around Adam Lang’s involvement in a CIA-sponsored “extraordinary rendition” torture outsourcing program.

Mrs. Styron’s argument is that the value many Vineyarders place on privacy would preclude such an invasive activity.

Readers can forgive Harris this slight melodramatic flair. After all, personal protests aren’t entirely unheard of; one Islander proudly remembers driving past Democratic presidential candidate Barack Obama’s temporary residence this past summer, blaring out the Grateful Dead from his car, “just to see what his security would do.” And during anti-Vietnam War years here in the 1960s, some protests got as far as Robert McNamara’s house in Chilmark.

But if one was heading up Harris’s legal defence team, looking for an O.J. Simpson-ill-fitting-glove clincher which would prove the book’s fictional status, one need not look further than his description of the Vineyard ferry experience. Firstly, he describes one passenger as going out onto the deck for a cigarette when this is clearly prohibited. A small factual error perhaps. But, in his drawing of Steamship Authority staff, the author dismally fails to capture their brisk — not to say terse — approach to customer relations. When he depicts a staffer as opening the narrator’s door for him and his offer of holding up the ferry, in this reporter’s opinion, he enters a Tolkeinesque realm of fantasy.

While spotting the real-life parallels and small errors of continuity is diverting, Harris’s book also works both as a thriller and as a satirical jab at a fawning British administration, intent to please the U.S. at all costs. And if Harris’s explanation as to why Britain is hopelessly in thrall to the U.S. seems to be outlandish ficton, the author has a real-world explanation ready.

“[Former British Prime Ministers] Thatcher, Major and Blair have all gone on to make fortunes in America after leaving office,” he says. “It’s the only country in the world that has this kind of post-political option. There is a relationship which has financial implications. I’m not saying that British foreign policy is run by guys simply looking at their own financials, but psychologically it’s got to be in the back of their minds — that popularity in the U.S. will translate to a lot of money. That’s worthy of reflection, I think.”

Comments

Comment policy »