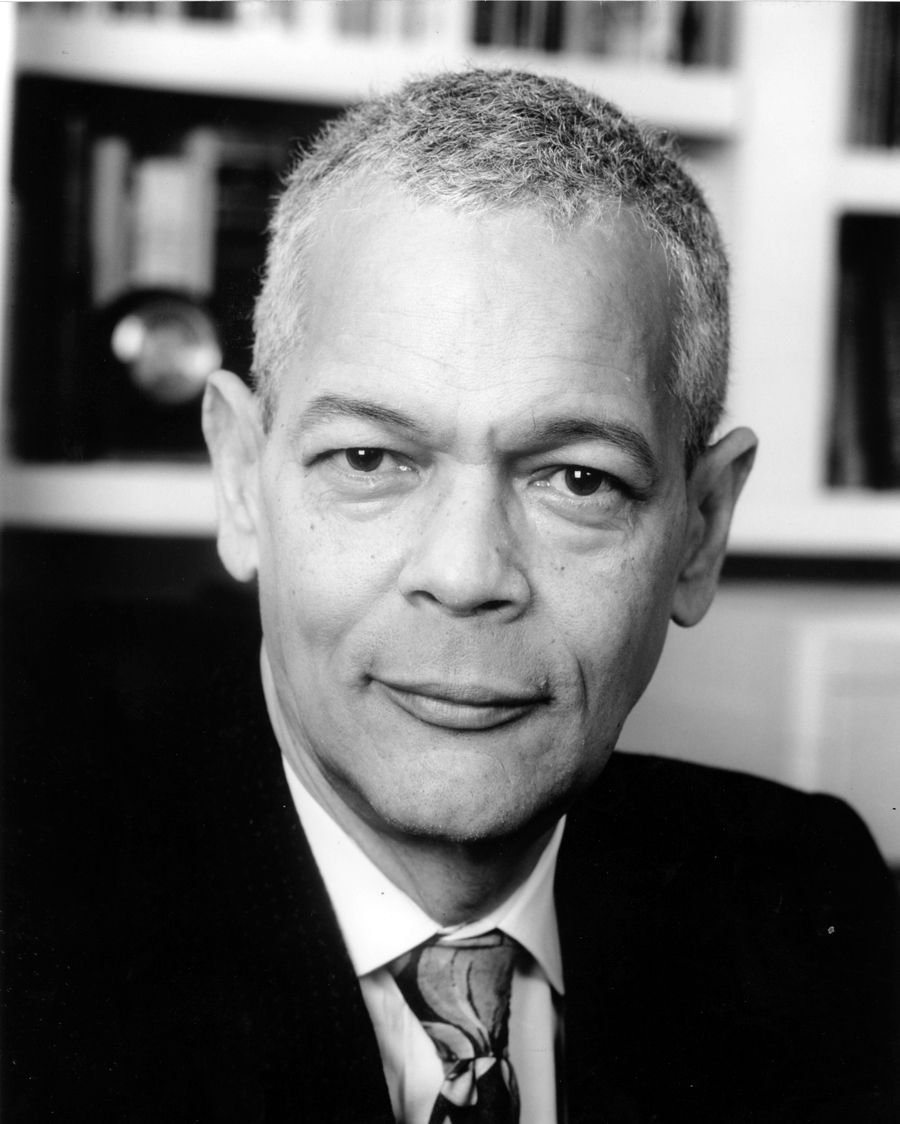

Henry Louis (Skip) Gates Jr. uses the quiet entrance, through the corridors of the Martha’s Vineyard Regional High School to a backstage area of the performing arts center, no doubt the sort of precaution he regularly takes since his arrest and high profile beer with the President last month.

But as he enters, he bellows with a theatrical gesture of his walking cane in the direction of his friend and legal counsel, Charles J. Ogletree Jr., the man he calls Tree.

As a navy-suited Mr. Ogletree directs the first speakers at today’s panel on race relations, he is grasping a nameplate for key civil rights figure William T. Coleman Jr., the lawyer who coauthored the NAACP brief for Brown vs. Board of Education, who also served as the United States secretary of transportation under Gerald Ford.

To his right is Judge Allyson Duncan, who was recently confirmed on the fourth circuit of the U.S. court of appeals, next to Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, Harvard professor of history and African and African American studies.

Behind him is Sonja Sohn, the actress who played the principled, whistle-blowing detective in the HBO series The Wire, and who is on sabbatical to run ReWired for Change, a nonprofit program for underserved communities across the country.

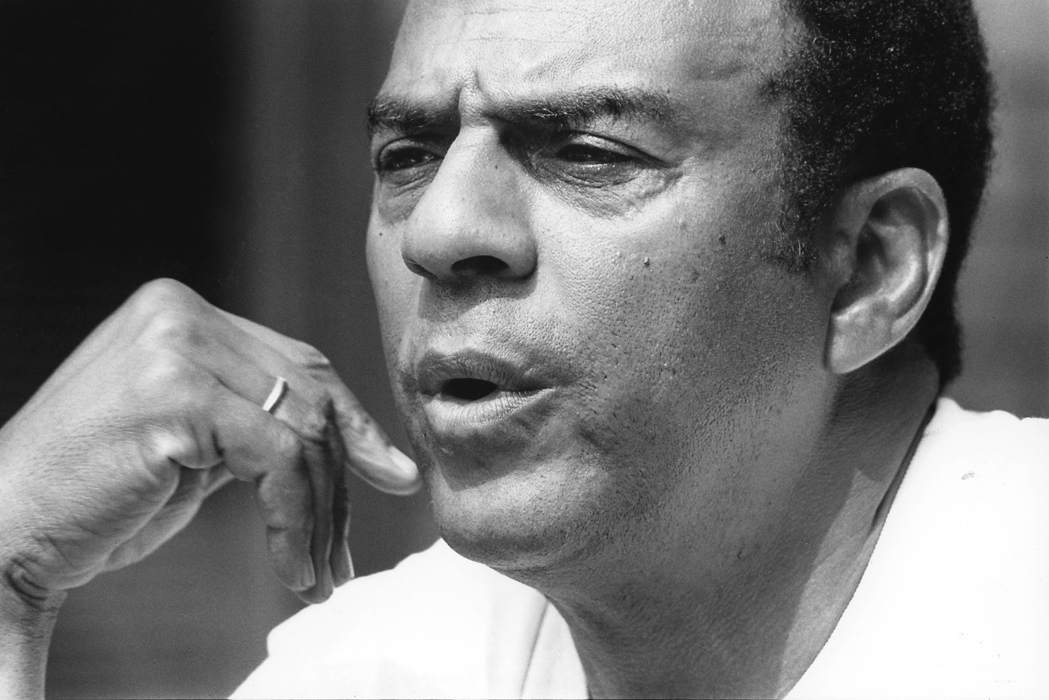

Mr. Gates, a filmmaker, writer and director of the W. E. B. Du Bois Institute for African and African American research, makes a brief detour toward a pastry table, and then with an ascetic pat of the stomach, joins the huddle around Mr. Ogletree.

The high school practice space is a makeshift green room this morning, housing some of the country’s most prominent African Americans, many of whom are drawn here on an annual basis.

The question is, why this particular 100-square-mile patch of land? What about the Island has proved inviting to generations of African Americans?

Mr. Ogletree ponders the answer, unfolding a chair in a busy hallway while the first speakers prepare to take the stage.

“This is the epicenter for intellectual and social dialogue in the country,” he says. “You look at the variety of people that are here: it’s not comparable to anywhere else in the world.”

Mr. Ogletree put on the first of these symposiums in 2006 in the wake of Hurricane Katrina — screening Spike Lee’s documentary When the Levees Broke. Now with corporate sponsorship, the event has become an annual institution. Part of the appeal for the professor is to remind vacationers of black history on the Vineyard.

“They should know about Adam Clayton Powell and Dorothy West. They should know about why President Barack Obama, Vernon Jordan, Charlayne Hunter-Gault and Skip Gates chose this over any other place.

“Intellectual discourse has always been here but it hasn’t always been documented. I can just imagine the conversations between Dorothy West and Langston Hughes in the early 1900s. The question was, will we ever overcome the issue of segregation and depredation based on race. I can imagine Vernon Jordan talking to the Clintons about the challenge of being president when confronted with the issue of the Monica Lewinsky incident and how to overcome that. I can imagine Skip Gates enjoying the ability to ride his tricycle around the Island but now forever having to remember being arrested on July 16 and what that has done to trensform his own existence here.

“I also know that a lot of young people find that this is the place where they made friendships for a lifetime.”

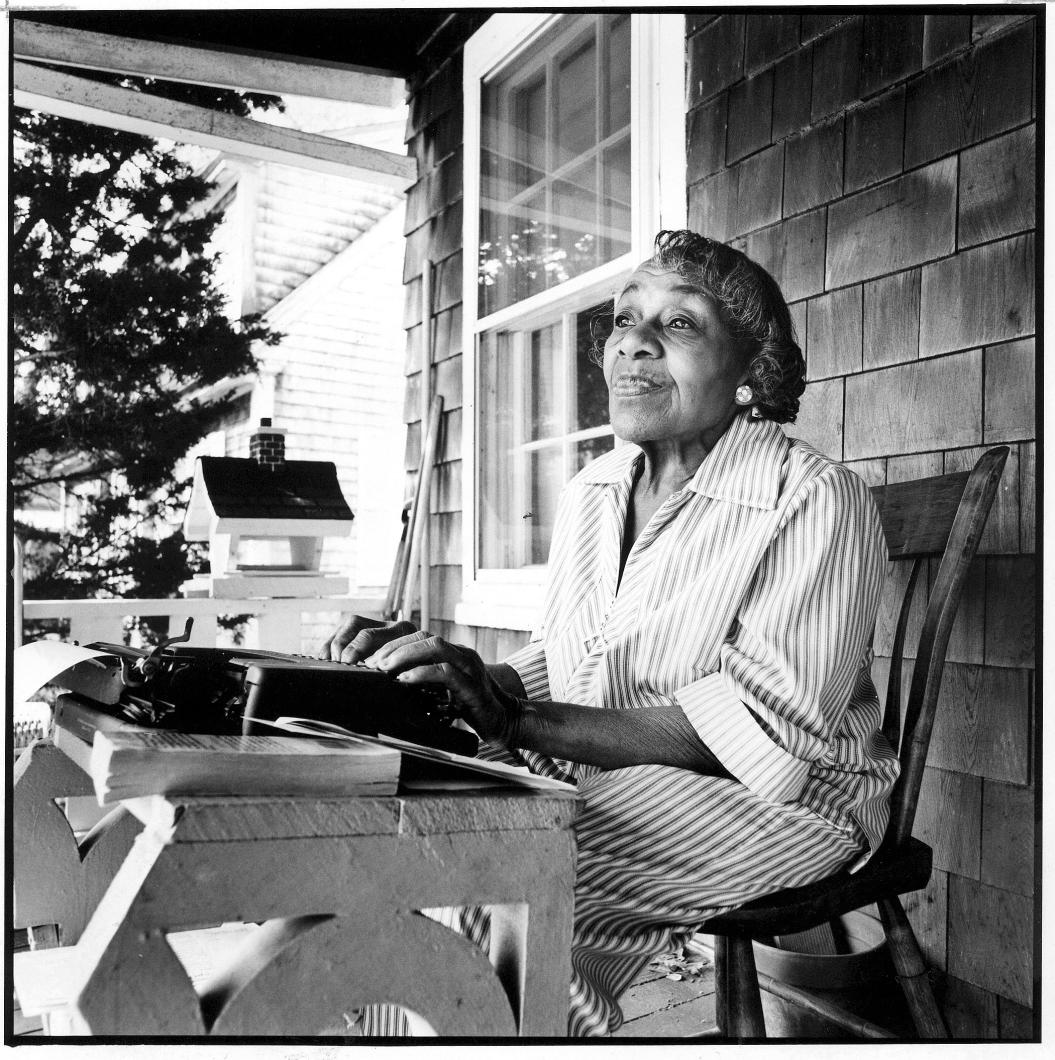

That’s how author Jill Nelson feels about it.

“It’s a place to vacation and meet people who, chances are you’ll have something in common with,” she says.

Ms. Nelson who has been a summer resident for more than 50 years and occasionally a year-round resident, said it is surprising to hear the media discover the world she found as a girl.

“I feel like it’s the starlet that gets recognized at 65, after acting for 45 years,” she says. “This surprising notion that there’s a black middle class and black people go on vacation.”

In her book Finding Martha’s Vineyard: African Americans at Home on an Island, she depicts a world in which children show respect, police are less than strict, and a leader of the Harlem Renaissance is a friendly neighbor.

“It wasn’t till I was almost grown and had known her for years and years as the tiny, birdlike woman with the thick Boston accent who talked faster than seemed humanly possible, whom I often saw around town, at the post office and occasionally on my mother’s porch, that I realized this friendly, talkative neighbor was also the famous writer Dorothy West,” she writes.

Ms. West, a longtime resident of the Vineyard, described the growth of that summer community in a 1971 Gazette article.

“Probably 12 cottages — all Bostonians . . . neither arrogant nor obsequious, they neither overacted or played ostrich . . . they were ‘cool’ — a common condition of black Bostonians.

“For some years the black Bostonians, growing in modest numbers, had this idyll to themselves . . . and then came the New Yorkers . . . [who] did not talk in low voices . . . talked in happy voices . . . carried baskets of food to the beaches . . . wore diamonds . . . dresses were cut low. They wore high-heeled shoes on sandy roads.”

Of course the racial history of Massachusetts is mirrored on the Vineyard — there are records of slaves kept long after the practice was made illegal, as was the case throughout the state, and there is a ample evidence of various practices of segregation.

Historian Elaine Weintraub, who is cofounder of the Martha’s Vineyard African American Heritage Trail, says there is also evidence of early cooperation between races.

“The Island was too small, too insular to fully commit to the racist and social class division that communities organize along the lines of. When you need personal relationships it undermines the divisions,” she says.

She uses the example of William Martin, an African American Vineyarder who in 1853 became the first black whaling captain.

“It was dirty and dangerous work and crews could be out for four years at a time. On the water, far more important than any other considerations was having someone in charge who knows what they are doing,” she says.

She also points to the example of the nearby small community of Provincetown, at the tip of Cape Cod, where in 1930s the Ku Klux Klan opened a branch of its organization.

“It began enthusiastically but it didn’t work out,” she said. “People may have believed in the myth of racism but there were just too many exceptions. The different races needed each other too much.”

For whatever reason, racism at least in recent history has played less of a prominent role on the Vineyard than elsewhere in the experience of many African Americans.

“Not to say that color’s not a difference here, but it’s not a big difference on the Vineyard,” says Robert Tankard of Vineyard Haven. “There’s more integration than anywhere else I’ve ever seen.”

Mr. Ogletree agrees, arguing that there are fewer private areas on the Vineyard (evidently forgetting the Island’s predilection for gated beaches).

“Martha’s Vineyard has been a receptive community to African Americans, particularly in the last century,” he says. “People from every walk of life look forward to seeing the absence of gated communities or having to have a pass to get from one place to another or being judged on what they wear or where they stay.”

Ms. Nelson gives a less rosy appraisal in her book.

“Certainly the Vineyard is not a racial utopia but it is and was better than most places,” she writes, adding a caveat:

“Or at least for the most part it seems that way, maybe because there has always been a finite, acceptable number of black families here.”

Indeed, the black community has always been proportionately small and seasonal, hovering between two and five percent of the total population.

Mr. Tankard first came to the Island at age 13 in 1959, one of seven lucky children — another three siblings stayed at home in New Jersey. Two years later he was living here full-time with his mother, who left Newark, N.J., in part to escape the racial tension there.

“There were kids from all over the country of African American descent,” he says. “A lot of them had professional parents — doctors, teachers, politicians coming from New Jersey; you didn’t hear much about that. I realized Bob Tankard could be anything he wanted to do be.”

To a large extent he found that the black community disappeared on the ferries on Labor Day weekend. The year-round Island population dwindled to between 5,000 and 6,000, and the vast majority of the African Americans he saw in the summer were gone.

“It was a little shocking,” he says.

But Mr. Tankard made good friends across color lines, in a way that he perceived would have been impossible in his home town.

“Chris Murphy, Allen Whiting . . . they accepted me as one of their own,” he says. “Tony daRosa’s parents didn’t say ‘. . . Bob, you have to stay outside.’ In New Jersey there were places you couldn’t even go. Meanwhile [on the Vineyard] in the summers I saw bigger and better things and I didn’t feel that limitation.”

Mr. Tankard joined the military after high school and was stationed for a so-called hardship tour in North Korea, which meant he was not reenlisted for Viet Nam. When he returned in 1968, he enrolled and went to Cape Cod Community College, later going on to the University of Massachusetts at Amherst for a master’s degree in health and physical education. Meanwhile, he became a teacher at and later principal of the West Tisbury School. A decade ago he received a doctoral degree in education leadership and change.

“If I’d grown up in New Jersey I might have been that baseball player, but coming here I realized I didn’t have to be that to succeed,” he says.

Mr. Tankard feels that the Obamas’ visit is a way for the President, who spent very little time on the Vineyard during his campaign, to thank a community for its support.

“With my background it really means a lot to me that he’s coming here,” he says. “I never thought I’d see an African American president in my lifetime. I think he’s coming to the Vineyard to say thank-you and it’s great to be around for that history to tell my grandchildren about.”

Comments

Comment policy »