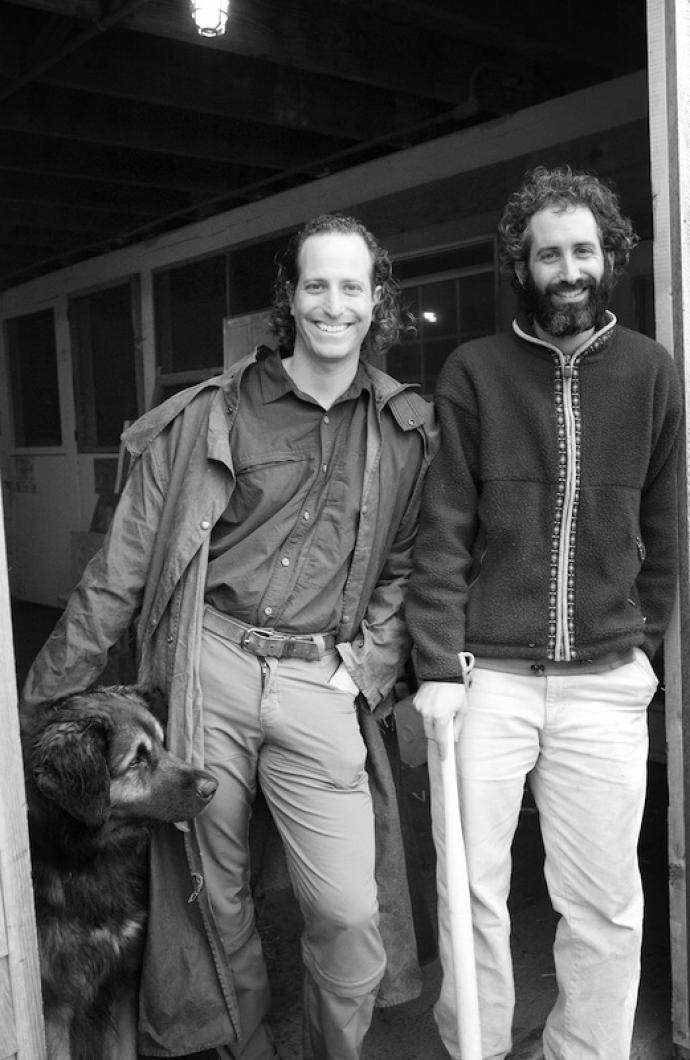

This year, the Farm Institute will lose two of its key leaders: brothers Rob and Matthew Goldfarb. Rob, development director, leaves today. Matthew, executive director, will depart at the end of this summer, after being at the reins for five years.

This week, the two sat down to talk about the Katama-based farm, its past and its future. For them, the Farm Institute is a classic community success story, with a beginning, a hardworking present and a future they feel will remain strong, well after their departure.

The two are leaving their posts for personal reasons, certainly not for a lack of love, interest or challenge. Rob wants to spend more time with his wife, Magda, a doctor from Guatemala studying in Chicago for her American medical boards, while Matthew plans to go back to school for a master’s degree.

In almost every word, the two speak passionately of the 162-acre, town-owned Katama Farm as both product and possession of the Island community. They speak of the cattle, cows, pigs, chickens and an alphabet of produce growing in the field, from apples to zebra-stripe tomatoes, and the joy of teaching thousands of children who have walked through the field — all of it made possible by the generosity of donors and the support of the larger community through the years. Throughout the conversation, they deflected attention away from themselves and on to the other ingredients in the Farm Institute soup.

But no matter how the story is cast, the Goldfarb brothers brought a gift of growth to the organization, a gift that can’t be measured in cash, soil, fertilizer, smiles or work. They brought an energy to the farm that wasn’t there before. On the eve of their departure, everyone’s hope is for that energy to remain behind, smoothing the transition to new leadership and contributing to the sustainability of the farm’s programs, both present and future.

The brothers, who have always had a close relationship, held intentions of developing a teaching farm well before either one set foot on Island soil. “We always planned to do a farm together,” said Rob.

Matthew was hired as farm manager in the summer of 2005, a time when the institute was stumbling. He’d never been to the Vineyard before. “I was at Iowa, at a Quaker boarding school teaching biology and developing a livestock farm program,” Matthew said. “I was here several weeks and the organization was going through a lot of changes, leadership changes, management changes, vision changes. I was offered the position of executive director and shortly after that, summer ended.”

By the end of the summer, Matthew was a staff of one. “I was the only employee left, and they charged me with figuring out how to run the organization and rebuild it,” Matthew said.

That first autumn, it was clear that the farm was in need of someone who could help the farm’s image, someone who could work with people and help share in the vision. It was a short-term assignment, a task that was more of a project than a job, and Matthew ended up seeking the help of his older brother. “I made a proposal to hire Rob for a one-time job, because he had done a lot of outreach and PR work,” he said.

Rob happily rose to the challenge, and his natural aptitude for the work was evident. “The board liked it. And then when I was in the process of designing new programs and staffing and pulling all that off, it was a job that Rob wanted.

And for both brothers, the opportunity was the realization of a shared dream. “The idea of working together, working with children, the land — the farm was something we had always talked about,” Rob said.

The Farm Institute is many things to many people: a school, a farm and a neighbor. When the Goldfarb brothers stepped in, the institute was a clean slate, and they saw a possibility. In terms of community programs, no one on the Vineyard was attempting anything like a teaching farm of this scale, though there were fond memories of the county-run 4H farm programs that ran in the past. The wheel that was being invented wasn’t entirely new, but it was big.

During that first season, it was clear to Matthew that, though the community could benefit from an educational agricultural center, there were obstacles. “One of the critical things in the early stages was that there wasn’t transparency. There was a lot of animosity, a lot of resentment, a lot of confusion and ambiguity. You didn’t have to be too smart about anything to pick that up. You read the papers, you look at the minutes of the conservation commission meetings and then you say: ‘How do you address that? You are never going to be successful if you don’t address that,’” he said.

In response to these circumstances, the brothers initiated a philosophical shift. “We have been very conscious about being transparent, because we believe we are a community-based organization, serving our community. They should be able to see how we work, how we serve, how we operate, how we make decisions and [that] builds a level of trust,” said Matthew.

A more positive relationship with neighbors was cultivated. Prior to the Goldfarbs, there were years of neighborly concern about smells coming off the town-owned fields and about the wellbeing of the farm animals. Between tenants, the farm often sat idle, and more than a few neighbors liked the fact that the fields were lush but not farmed; pretty but not productive.

“We still do get some of the concerns from neighbors,” Matthew said. “But we have more open dialogue. We’ve proven that we want to listen to what their concerns are. We can’t always accommodate them, but we want them to know that we will work with them, rather than take diametrically opposing sides.”

Rob said: “It really is persistence. Being able to make [the point] that this is your farm, that was the big approach in 2005.” Further, Rob said: “It is not my farm, it is our farm. It is not the town’s farm. It is everyone’s farm.”

To the credit of all involved, including the animals, Rob said, today they are hearing a different kind of concern. “Now some of those neighbors are asking, ‘Hey, we don’t see the cows any more. How come they’re moved?’ Matthew is always moving the cows. Now they are saying, ‘Where are the cows? Put them back in our field,’” said Rob.

A key ingredient for the farm’s continued success lies in fostering openness and the welcoming spirit that attracts new people. The brothers’ vision for the farm and the community spreads as more and more people came to the farm. “Our mission is to engage people in sustainable agriculture. There are a million ways to do that: write pamphlets, write books, go on lecture series. You can feed people, so many different ways. We asked, how do we get people down to the property? Maybe they will come for music, or a cooking gig, or the corn maze. But while they are here, they get exposure to this community farm. Maybe they’ll come back and have a picnic. Maybe they will come back and bring a grandchild. It was a conscious effort to expand the idea of education and engagement,” Matthew said.

Rob adds, “I think the most meaningful complement [to what Matthew just said] is the fact that it was about relationships. That is the real currency. My job is to make money and not treat donors like ATM machines, but to really treat them as people. It is relationships, and for me, it is connecting and building hundreds of relationships, whether it is with farm families, children in the programs, businesses, staff, volunteers, neighbors, the board or other farmers.”

The brothers will miss the farm, just as much as the many people they have touched and taught will miss them. Fortunately, the opportunity for a proper goodbye is on the horizon: they are both looking forward to Meals in the Meadow, the institute’s big annual fundraiser on July 17.

If the two had the opportunity to do it again, they both say about the same thing: “If I could do it over again, I would have carved out more time to be a teacher,” said Matthew.

“I ran the summer programs for two years,” said Rob. But changing responsibilities found him spending more time in the office, hearing indirectly about the children’s work out in the field. “I only got to hear about it from the staff. I’d read about it in their reports. I missed that, being out there.”

Comments

Comment policy »