One spring morning in 1972, while riding his motorcycle across a bridge in New Jersey on his way to class at Fairleigh Dickinson University, William Marks glanced over the side to the river below and saw dead fish. Lots of dead fish.

A sophomore studying business management on a lacrosse scholarship, he had no reason to investigate the fish kill other than his natural curiosity. He climbed off his motorcycle and headed up the bank of the river on foot, eventually coming upon some industrial buildings, out of which pipes could be seen discharging waste into the river. He paused there, considering the possibility that toxins in the discharge might be the culprit, but as he stood in the water he noticed another dead fish coming down stream. The source was farther up.

The day grew hot, and he had to stash his motorcycle helmet and jacket in the weeds. Soon he encountered a construction site. A new section of highway was being built, and the river had been diverted. A channel curved around the work area; the original riverbed was filled in with dirt and covered by tracks that traced the dance of heavy machinery. Where the channel reconnected to the river, it was shallow, and the water contained a lot of silt. He deduced that the fish native to this river were unaccustomed to such a drastic change in environment. Here was the source of the fish kill.

Having already missed his classes, he hurried back down river to his waiting bike and rode on to lacrosse practice. He did not think much of his discovery until the weekend when he picked up a local newspaper and saw headlines and a story about the fish kill. Scientists were baffled as to the cause, the newspaper reported. He followed the story for about a week. An investigation came up empty. He called the paper.

“I know what caused the fish kill,” he told the editor. “Who are you? Are you an expert?” she asked. “No. I’m a sophomore at Fairleigh Dickinson University,” he replied

A few days later, a skeptical reporter and a photographer joined Mr. Marks to retrace his steps from the week prior. His theory was verified, and the paper published the story. “Student Discovers Source of Fish Kill,” the headline read.

So began William Marks’s lifelong relationship to water.

Today the 61-year-old Katama resident has a long list of distinguished accomplishments that on their own would fill an entire newspaper story: among them, former water quality planner for the Martha’s Vineyard Commission, author, magazine founder, publisher and editor. He has been the subject of a documentary film and is accomplished on the Native American flute.

He even has legally changed his name to William Waterway.

To that end, Mr. Waterway has helped produce a water-themed event planned for this weekend sponsored by National Geographic that will include the launch of a new book, a film premiere, panel discussion, poetry reading and concert. Titled Water Is Life, the event takes place on Saturday and Sunday at the Whaling Church in Edgartown and the Katharine Cornell Theatre in Vineyard Haven; details appear in a story on Page Two-A in today’s edition, and in a paid advertisement on Page Nine.

But back to the New Jersey fish kill incident in 1972 and the man who would become William Waterway.

He returned to the river to investigate the waste products being discharged by the factories, which turned out to be owned by a paper company. He took photographs of the pipes, and took samples, despite knowing nothing about water testing. He brought the samples back to campus, to the chemistry lab there, where he learned the basics of laboratory analysis from the students and faculty. “The school probably would not have allowed it if they knew what I was doing,” he said.

After testing showed the presence of toxic pollutants in the water, he began reading environmental law and discovered an old piece of legislation: the 1899 Refuse Act, which declared any information on pollution of a navigable waterway known by a citizen would make the citizen eligible for a percentage of the fine levied against the polluters. “I supplied the information, photographs, samples and analysis to the U.S. Attorney’s office, and the grand jury worked to corroborate my results by doing additional testing on evidence that I supplied. It was solid enough that the company was indicted on 20 counts despite the fact that the local and state boards of health defended the company, saying that they always passed inspection,” he recalled.

The paper company eventually was brought to trial and convicted, and the student activist received a check for just over $3,000. One newspaper photo caption called him a “pollution bounty hunter.”

And Fairleigh Dickinson University gave him an office, to continue his work.

Looking back — he was raised in rural New Jersey on an organic farm — Mr. Waterway feels that his life has taken a natural course.

“I never saw what I was doing as a mission. I’m doing the thing that makes me feel alive, gives me purpose,” he said in an interview at his Katama home last week. “I had some pretty cool offers come my way along the trail . . . jobs in banking, precious metals. But I didn’t want it.”

After college, he continued to focus on water ecology. He became a senior environmental analyst for the city of Newark, the first ecologist in America to be hired by a city. Though the position afforded him considerable resources and power in terms of enacting policy changes and putting protections in place to improve the city’s water supply, he felt too confined.

One day, while at a meeting with the New York and New Jersey Port Authorities in the World Trade Center, he was struck by a vision of a man on horse, riding down a mountain toward a river. He decided to resign.

“I want to ride a horse across the United States,” he told his incredulous boss. He sold most of his possessions and flew to San Diego, carrying only a checkbook and a toothbrush.

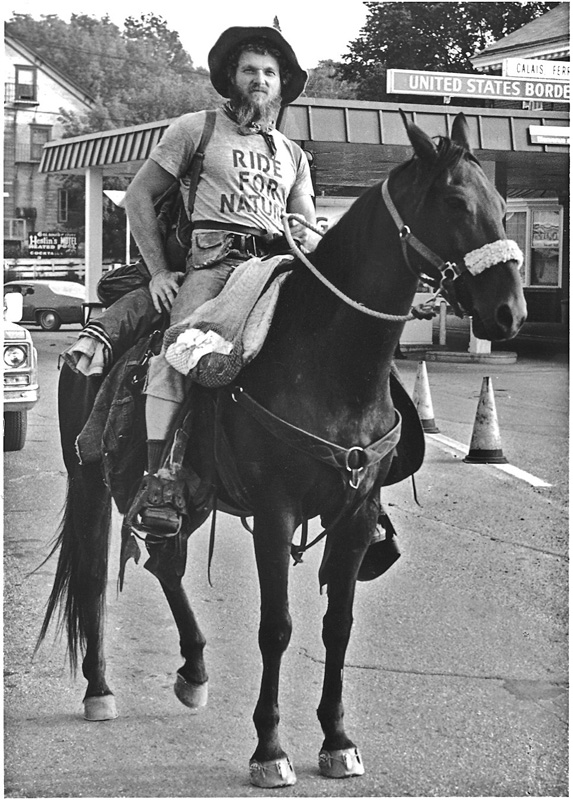

The ride covered 7,000 miles, from California to Maine, passing through thick forests, vast deserts, bustling cities and quiet suburbs. The idea was to investigate the state of the nation’s water resources at ground level, as well as focus public attention on the issue of clean water. He remembers experiencing thirst, fear, hunger, isolation and pain, and also intense gratitude for the natural world.

After the journey ended, he settled at the Warren, Conn., farm of a friend.

In 1978, he moved to a small cabin in West Tisbury without electricity or plumbing; within a year he was hired by the Martha’s Vineyard Commission as the Island’s first water quality planner. “For the most part, there was little-to-no water consciousness on the Island then,” he said.

Bureaucratic conflicts led to his being fired from the commission. Regrouping, he founded the Vineyard Environmental Research Institute, which focused on evaluating water quality, and Vineyard Environmental Protection Inc., the Island’s first state-certified water testing laboratory.

In 1984, at the age of 34, he had a heart attack. He was still living in the rustic cabin in West Tisbury at the time. The next year, he once again liquidated his savings and founded the Martha’s Vineyard Magazine and Nantucket Journal (now named Nantucket). “We came out with the first issue [of Martha’s Vineyard Magazine] in 1985. Walter Cronkite was on the cover — he wrote an awesome article about the Vineyard and his relationship with water. I published the magazine for six years before selling to the Gazette,” he said.

The sale in 1990 was a necessary move, as his heart had begun to malfunction again. Told by doctors he had no choice but to install a pacemaker and a defibrillator, he decided to return to his cabin on the Vineyard. “They told me they had to wrap my heart in wires; that was the only thing that would save my life,” he recalled. Instead he tried an ancient healing practice of applying alternating hot and cold water on his chest and back, near the heart.

His brush with mortality inspired him to write a book to record all his knowledge and experience with water. The Holy Order of Water was finally published in 2001.

And Mr. Waterway recovered. His involvement continued in a wide array of water issues, including wastewater.

Today he is frequently asked to visit conferences and join panel discussions around the world to speak on various aspects of the human relationship to water.

His recent work includes an essay he wrote for the National Geographic book Written in Water, to be released this weekend. Titled A Ride for Nature, the essay recalls his experiences during his cross-country horseback ride.

“There’s a payoff for the soul, choosing where I spend my time. People accumulate these cars and houses and all these nonliving objects and then they die and it all rots,” he said. “I had people tell me, there’s no money in ecology. But I knew I couldn’t live with all the rules, restrictions, pretensions. I wanted to be free. For me to have the freedom to go where I wanted, when I wanted. To help the other life forms that I grew up with.”

Comments (1)

Comments

Comment policy »