Emma Goldman was a woman who championed women’s rights to contraception, workers’ rights, homosexual rights, and who spoke against militarism, capitalism and religion.

These days, much of what she stood for is mainstream, or at least within the ambit of mainstream debate. But back in 1919, her views and her philosophy, anarchism, were enough to have her repeatedly jailed and, ultimately, deported from the United States to where she was born in Lithuania, then part of the Russian empire.

Along with hundreds of others, she was rounded up — in an operation overseen by a young J. Edgar Hoover — in middle-of-the-night raids. She later wrote about it, and about the irony of catching sight of the Statue of Liberty, even as her liberty was being taken.

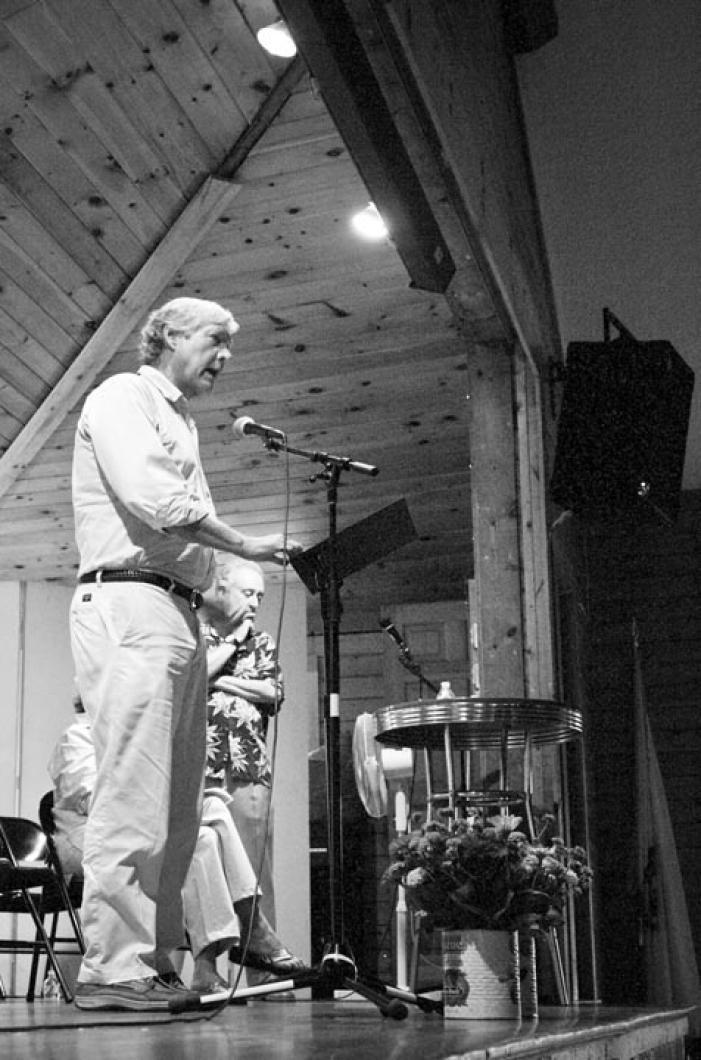

There’s no denying Emma Goldman wrote powerfully. No wonder the forces of reaction were afraid of her. It was a portion of that writing which kicked off last Thursday night’s presentation of readings by the American Civil Liberties Union, An Evening Without: Giving Voice to the Excluded, to a capacity crowd at the Chilmark Community Center.

And it was a good way to begin, not because her exclusion was the most egregious example among the 14 writers who were at various times considered a threat to this country, but because it served to show just how long is the history in this country of attempts to ban ideas by banning people. And how pointless, for ideas stand or fall on their own merits. Emma Goldman’s views on contraception prevailed; her anarchism became anachronism.

History lends perspective. The nation’s fear of anarchists in the early part of the last century seems so insubstantial now, compared with the new fears which have supplanted it.

And that was exactly the point of the evening, of course. To suggest that maybe those new paranoias are equally insubstantial.

It was driven home by 14 distinguished readers, reciting words from the 14 distinguished banned persons. After each recitation, the reader left the stage, so by the end it was symbolically empty.

And between readings, the two hosts, Carol Rose, the executive director of the ACLU in Massachusetts, and Arnie Reisman, writer, producer and performer, gave historical context.

Thus we saw how the paranoia about anarchists became fear of communists, which became fear of terrorists. And how, in each instance, it has had ridiculous and sometimes tragic consequences.

Like the banning, in 1952, of the great British novelist, journalist and World War II intelligence agent Graham Greene, barred from the U.S. in 1952 for his brief membership in the communist party. The ban was lifted after four years when the state department realized his party membership had been a joke.

Or the case of Gordon Kahn, the Oscar-winning screenwriter who helped found the Writers’ Guild, who was presumed a leftist by the House Un-American Activities Committee although he was never called to testify, lost his job with Warner Brothers as a result, and was harassed from 1947 until his death in 1962.

Or Gabriel Garcia Marquez, a Nobel laureate considered “inadmissible” from the 1960s to the 1980s, but who never found out why. Or Carlos Fuentes, denied admission through the 1950s and 1960s, who later became Mexican ambassador to France and later taught at Harvard, Columbia and Princeton.

The list goes on: Nobel laureates Doris Lessing, Pablo Neruda, Dario Fo and Czeslaw Milosz, all denied admission at various times on vague or no apparent grounds.

Most notable of all the banned persons, of course, was Nelson Mandela, banned along with other members of the African National Congress who opposed apartheid in South Africa.

The man who steered his country from institutional racism through the peace and reconciliation process was only granted a waiver from his banning in 2003; the ANC was removed from the terrorism list in 2007 as a 90th birthday present from Congress.

The writings and readings were often moving, but sometimes funny. Dario Fo’s “dear fellow actor” letter to President Reagan, was a very clever, if somewhat long piece of satire.

Even funnier was the reading about the case of Farley Mowatt, the Canadian naturalist and author whose name somehow got on the state department’s “lookout list,” preventing him from doing a book tour in this country. Mowatt’s issues are largely environmental, his politics about as left as the Canadian Green party, and his writings sometimes humorous.

Mowatt’s reading quoted some of what had been written in U.S. papers about his banning, including these:

“Farley Mowat is dangerous. He is pro-wolf, pro-seal and pro-deer. He has admitted to fear in wartime. Worse, this man is a writer. His weapons are words. They cross boundaries, evade radar and can be shut down only by better words, which are few. Sometimes they become images on film and can penetrate where even words will not go.

“If we let such a man into the country, he would probably try to save the Rockfish. He is beyond redemption.”

But it’s not really funny, this paranoia which repeatedly grips America, and the last reading of the evening drove the point painfully home.

It was a poem of surpassing beauty by Moazzam Begg, a British-born Muslim, imprisoned for three years as a suspected “enemy combatant” at Bagram air base and Guantanamo Bay before being released in January 2005. Without charge.

Comments

Comment policy »