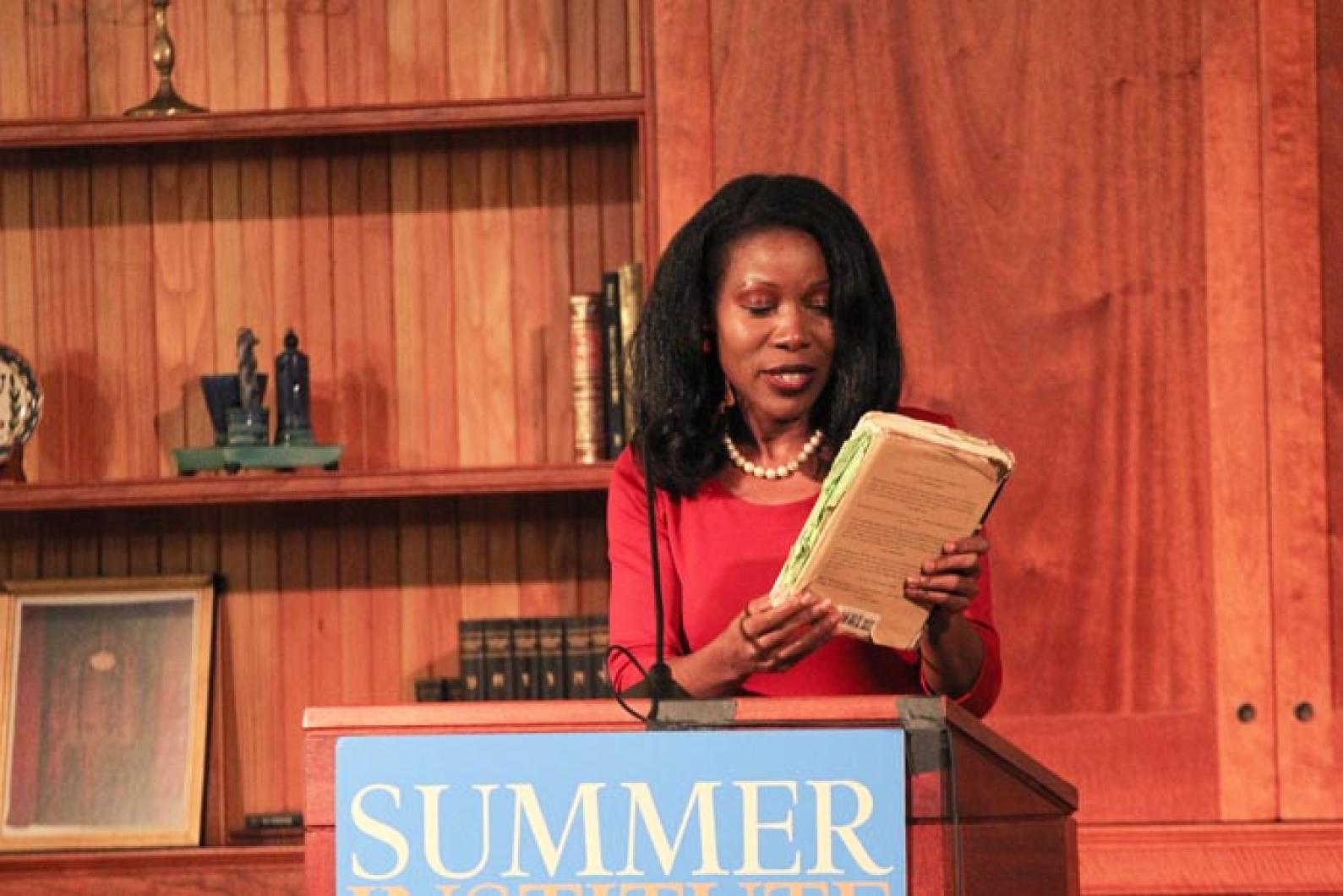

“These people did what the Emancipation Proclamation could not do, what Lincoln could not do, what the North and South alone could not do,” Pulitzer Prize-winner Isabel Wilkerson said, outlining one of many legacies of the Great Migration, which she chronicled in The Warmth of Other Suns, her epic account of this demographic seism.

“They freed themselves.”

In her lecture to a standing-room-only crowd at the Martha’s Vineyard Hebrew Center last Thursday, Ms. Wilkerson made clear the historical importance of this overlooked piece of our national narrative. “This is the greatest underreported story of the 20th century. It wasn’t in the history books. I didn’t know that much about it, and my parents were a part of it.

“This is a universal story that is the American story. It was a referendum on a place and time, and all the people who left where they lived were proxies for anyone who left the only place they’d ever known.”

A domestic migration is not the typical story that comes to mind when imagining the struggle of immigration and relocation, but these stories mirror the other migrations to America that began in the early 20th century and continue to this day.

“In some respects, this is the story of all of us,” Ms. Wilkerson said. “It is an unrecognized immigration within our borders.

“People had to leave the region of their birth in order to be recognized as citizens in their home country.”

Another thesis she offers in her book, and a central point of her lecture, offered a new perspective on the history of the American South, slavery and race relations in this country.

“In my book, I don’t refer to racism, and I could go into why. But I think you get a better idea of what life was like when you think about the structure of society and the needs of the economy that dictated social interaction.

“It was an artificial hierarchy, and the system was so arcane that it was illegal for black and white people to play checkers together. There was a black bible and a white bible for people to swear on in court. We all know about the bathrooms and the water fountains, and that might not have set off the great migration, had it only been that, but every aspect of human interaction was regulated,” she explained.

African Americans were held captive to that system until World War I created a demand for cheap, unskilled labor in the North. This simple economic issue gave six million people the opportunity to seek a better life, to find freedom.

Ms. Wilkerson was careful to hammer the point that this was not a careless migration. Rather there were three main routes that people took to find a new life.

“It wasn’t a haphazard unfurling of lost souls,” she said. “There were very specific routes, and it was an orderly way of getting out. This is the way that people migrate, and it’s a beautiful way: You can often tell where an African American person’s forebears are from, based on what northern or midwestern city they live in.”

People from Mississippi and Alabama traveled to Chicago, and other metropolises of the Midwest. From the eastern seaboard — Georgia, the Carolinas and Virginia — African Americans went north to New York, Boston or Washington, D.C. California became home to migrants from Texas and Louisiana.

In her travels to interview 1,200 participants in the Great Migration, she met several people in New York who not only had come from the same small Virginia town, Petersburg, as her father but had known him before they all sought a brighter future in the North.

“There is a wondrous predictability and continuity in any migration, and people recreate their culture wherever they go.”

And in recreating that culture, they gave America an incredible legacy in music, literature, sports, food and language.

“Every migration is for the children, and this migration created people who helped change American culture and world culture.

“Take Toni Morrison. Her talent would never have been realized in a caste system. She grew up in Alabama, and they didn’t permit African Americans to go into libraries. Her parents moved her to Ohio, and she could get into a library. If you’re going to be a Nobel laureate, you need to get a book every now and then,” she said with a laugh.

“Motown wouldn’t be here, jazz wouldn’t even exist. Miles Davis, Theolonius Monk, John Coltrane — those are gifts to the world.”

Without those individuals, and the millions more, America as we know it would not exist, both in our culture, our politics and our history.

“Ultimately,” said Ms. Wilkerson, “the story in this book is the about the power of the individual. It’s a lesson, an inspiration, and there’s a sense within all of us that here are the answers to every question we might face. If they could do what they did with nothing, there’s nothing that we can’t do, and so much that we must do, to make their sacrifice worth it.”

Comments

Comment policy »