The small hand of fourth grader Victoria DeMatos shot into the air. “I have a question,” she said, commanding the attention of the teacher, Shannon Carbon. “Shuns, is it, t-i-o-n-s?”

Answering in the affirmative, Ms. Carbon began to read aloud the story, The Nights of the Pufflings, which describes the efforts of Icelandic Islanders to care for the puffin chicks that get lost in their village.

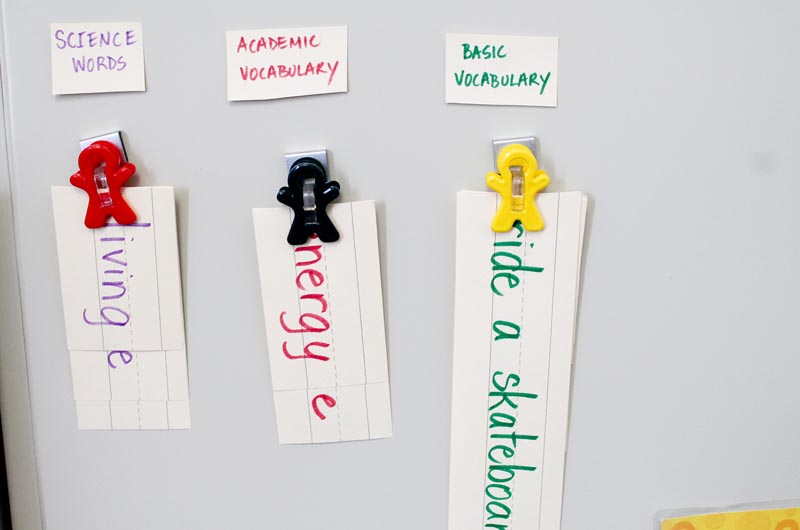

Words were discussed; hand gestures illustrated their meanings: burrows, speckled, surf, cliff.

“When I was learning about mythology, Hera threw her son off a cliff,” Emanuelly Nascimento informed her peers in clear English.

That same fourth grader did not speak three words in English last May when she entered the Tisbury School.

She’s one of 45 students at the school who speak more than one language, and one of some 140 nonnative English speakers in the public schools across the Island, the highest count in recent memory.

“We are at the highest level we have ever had,” confirmed Leah Palmer, director of the Islandwide English Language Learner (ELL) programming in the public schools.

A total of 128 students enrolled in public schools are native Portuguese speakers.

And most are second generation U.S. residents.

Their families come from Brazil, Jamaica, France, Spain, Uruguay and Thailand.

And there are more to come. Currently, 39 ELL children are enrolled in childcare centers Islandwide, and it is believed that many more spend the day in home care situations.

One of 18 ELL kids at the regional high school, Chanaporn Eksiri gladly gave up her Thai uniform for a Vineyard Basketball T-shirt and jeans when she enrolled last year.

Her biggest hurdle here is English, a language with many unfamiliar sounds.

She spends six hours per week with ESL (English as a second language) teacher Dianne Norton, who helps her in all her academic subjects.

Outside of the ESL class, Chanaporn’s other teachers also help her to keep apace with the rest of the class.

“In math class, if I don’t understand, the teacher comes and tries to explain it to me,” she said.

Soon, however, the ELL coordinators won’t be the only ones required to prepare for class with kids in mind for whom English is a second language.

For many years, the Island schools have trained educators in teaching speakers of other languages. But the Island has historically been ahead of the curve, Ms. Palmer said.

In 2011, an investigation by the U.S. Justice Department found that on the whole, schools in the commonwealth were not serving the needs of the English language learner population. Specifically, the state was not doing enough to equip teachers to teach students with limited English proficiency, and reduce the achievement gap between those and mainstream students.

In response, the state Department of Elementary and Secondary Education passed new regulations called Rethinking Equity and Teaching for English Language Learners (known as RETELL) in 2012.

The regulations dictate that by July 2016, all core academic teachers who have at least one ELL student in their classes must undergo specialized training. The regulations also mandate training for the principals, and assistant principals.

This Sheltered English Immersion (SEI) training will be offered to Island teachers and administrators beginning in the fall.

While primarily focused on helping students acquire English language skills, the ELL staff also values the linguistic heritage of the Brazilian student community.

“I made a concerted effort to call myself the teacher of children who speak two or more languages,” Ms. Carbon said after her students had scampered off to their next class. “If you have both Portuguese and English, it gives you so many more choices in this life,”

Some parents enforce the use of both languages, and some parents do not, she said.

Many take ESL classes themselves, but tend to gravitate towards people they are similar to and share common experiences with, just like any other group, Mrs. Palmer said, which can limit their English-speaking fluency.

For Ms. Carbon, nurturing her Tisbury pufflings means equipping them with the language skills they need to safely set sail.

“My goal is for them to go to college, have the opportunity to choose whatever they want their future to be,” she said.

An earlier version of this story incorrectly reported the percentage of Ell students who are second generation U.S. citizens. The story has been changed.

Comments (16)

Comments

Comment policy »