Down a long dirt road in West Tisbury stands the Mayhew Chapel, a modest one-room building with 185 years of Island history.

In the mid 1600s, Thomas Mayhew was the first minister in New England to convert Native Americans to Christianity. According to some accounts, on the day he sailed to England for the last time, members of his congregation wept in sorrow.

His return to England was in the hope of gathering support for his continued work as a missionary. But he never returned. The ship was believed to have sunk with all on board.

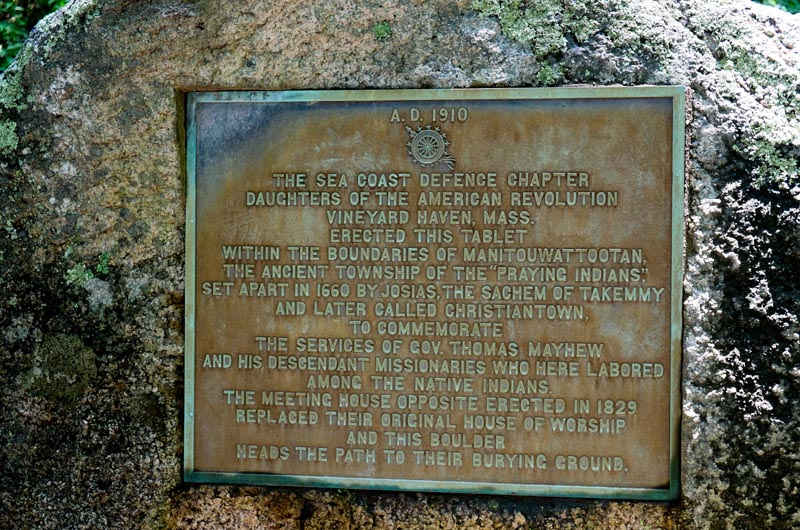

The chapel in West Tisbury was built in 1829 to replace an earlier one that had burned down. The site is where Reverend Mayhew had preached to his congregation. Across the road, a tablet commissioned by the Daughters of the American Revolution and embedded in a giant boulder commemorates Mr. Mayhew’s service to the Native Americans.

The chapel was part of Christiantown, a one-square-mile village given by the Sachem Josias in 1659 to four Christian members of the tribe, and later designated as a township for the Island’s community of Praying Indians.

In the 1980s Christiantown was awarded special place recognition by the state Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs. In 1986, the land to the northwest of the chapel was acquired by the Martha’s Vineyard Land Bank, in part so that the setting of the chapel “would not be spoiled by houses.”

At least four renovations were made to the building in the 20th century, the first being in 1908. Following several years of lobbying, the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah) assumed ownership from the Dukes County Commission in 1993 and set up a Christiantown committee to maintain the site. Further improvements were made, including a new roof, but over the years the chapel has fallen into disrepair.

Today the weight of history is more apparent than ever in its moss-covered roof, peeling white paint and crumbling ceiling. A peek through the windows reveals 15 small, tidy pews, a small wooden altar and a large pile of broken plaster.

Bettina Washington, tribal historic preservation officer for the Wampanoag tribe, said the last time the building was used was two summers ago.

Some of Ms. Washington’s family members were associated with Christiantown, and she remembers visiting the chapel as little girl. She believes the site still holds significance for the tribe, but for reasons that may be under recognized.

“Christiantown was a sacred site to begin with,” she said. “It was significant before it was a Christian place.” She said it was common for early missionaries to exert influence over native communities by destroying sites of traditional importance, or taking them over for other purposes. The site’s original name, Manitouwattootan, translates roughly to “the place of spirits.”

There are still people in Aquinnah and on the Cape whose family members lived in Christiantown, Ms. Washington said. The living connections have diminished over the years as people have moved away, “but it’s always been an Indian place.”

New efforts are underway to restore the chapel, clear out the underbrush in the burial ground and take inventory of the ancient fieldstones that mark the graves.

“To have the burial ground cleared, I would definitely say by next summer,” Ms. Washington said. “Whether the chapel will be done by then or not I can’t say for certain.” She said the goal is to obtain funding for repairing the chapel’s roof, ceiling and windows. “The pews are in pretty good shape,” she said.

The tribe has placed flags in the burial ground to mark the stones, which are almost completely overgrown. Part of the tribe’s work will involve distinguishing between headstones and footstones, because there was a period during which both were used. Ms. Washington believed that only one or two of the stones were inscribed.

In the past, the tribe had been more guarded about the site being open to visitors, she said, since the burial ground is open only to tribal members. “That was one of the issues about the burial ground — at one point we really were kind of hesitant to make it more inviting,” she said. One concern was over visitors to the chapel wandering onto the sacred site. “I wouldn’t say it happened all the time,” she said, adding that “it hasn’t been an issue for awhile.”

She believes that increased residential traffic on the road, along with traffic on the land bank trail, will help discourage people from intruding on the burial ground.

Another reason for the chapel’s gradual decline was its lack of heating and electricity. Because it was rarely used in the winter, new damage would often go unnoticed until the spring. The tribe kept putting off repairs until the following year, Ms. Washington said. “Now we can’t wait anymore.”

She continued: “Sometime between now and Cranberry Day [the second Tuesday in October] I would say we’re going to sit down and talk about how we are going to move forward on this and make it a priority,” she said.

Years ago, when the chapel was open to the public, Wenonah Madison used to lecture there about Wampanoag history. There were also small weddings from time to time, which helped fund repairs. The chapel will again be available for weddings when it reopens, Ms. Washington said. She also hopes to have someone there on weekends to greet visitors and answer questions.

“We feel we really need to do this,” she said. “It’s a piece of our history and we don’t want to just let it go by. To have the opportunity to share that with people, whether they are from on-Island or off-Island — it shouldn’t be forgotten.”

Comments (1)

Comments

Comment policy »