Nelson Bryant remembers playing marbles under a giant maple tree near the West Tisbury town hall, fishing for trout with a childhood friend in Mill Pond and trapping muskrats for his neighbors for a dollar apiece.

For Mr. Bryant, who first came to the Vineyard in 1932, his surroundings are an ever-present reminder of days gone by.

Approaching his 90th birthday two years ago, he began writing his memoir, Mill Pond Joe, which chronicles his early years on the Vineyard, his many near-death experiences during World War II, his career as a newspaper editor in New Hampshire and Massachusetts, and 30 years as outdoors columnist for the New York Times, among other experiences. The memoir was released in September.

Part of Mr. Bryant’s intention, he said, was to show what the Vineyard was like 80 years ago, when residents were far fewer and wildlife was more abundant. In West Tisbury alone, he writes, the year-round population swelled from 270 in 1930 to just over 3,000 in 2013. The Island’s year-round population increased from about 5,000 to over 17,000 in the same period.

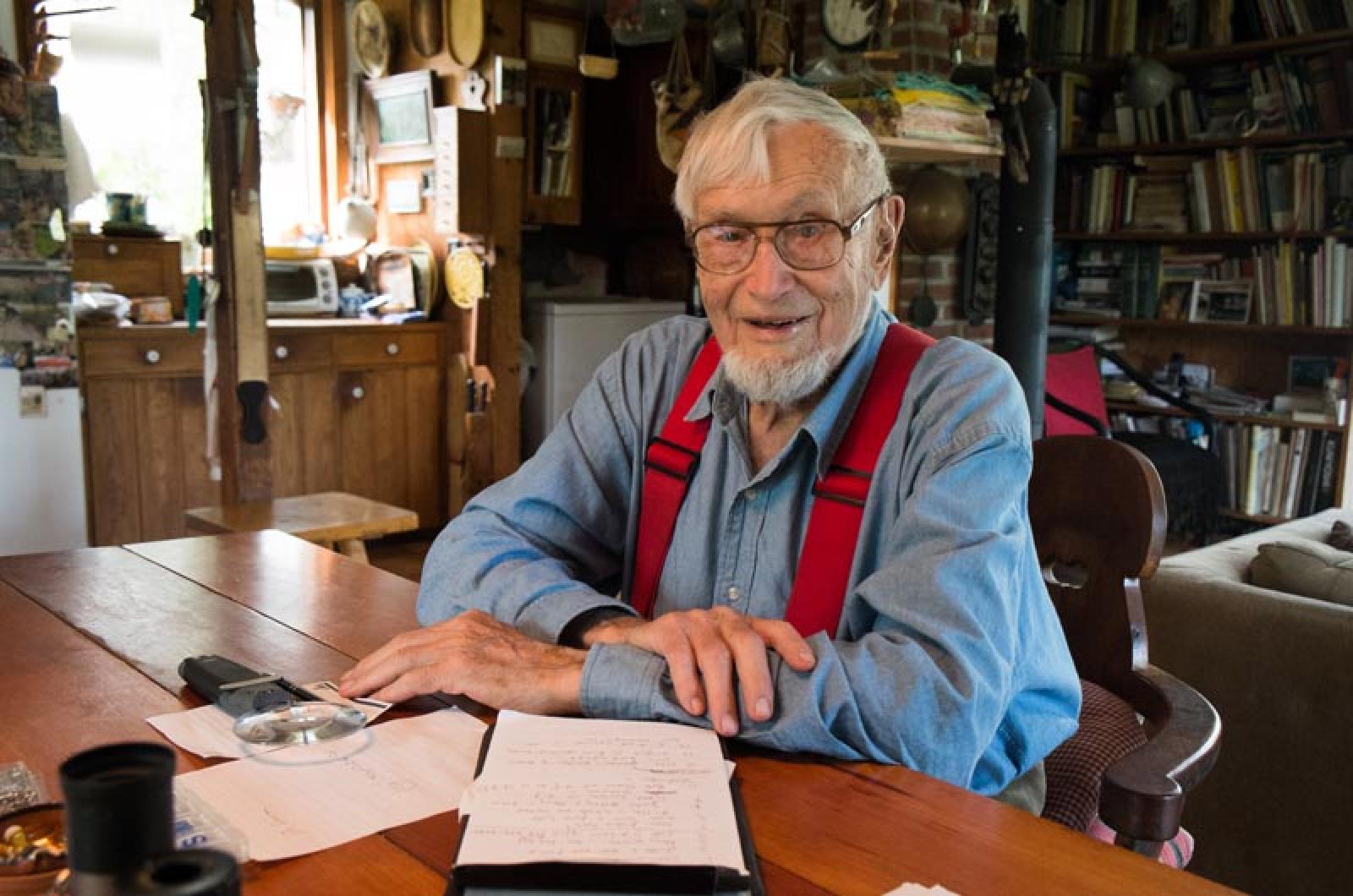

“Within five miles of here there were less than half a dozen kids,” he said on a recent morning during an interview at his home in West Tisbury. “So you had to do some walking or bike riding to find a buddy.”

Mr. Bryant’s home is nestled among beetlebung and apple trees behind the house where he grew up. Nearly every wall is covered with photographs and paintings, including woodcuts by his partner, Ruth Kirchmeier, who bought the house years ago with her former husband, Rolf Ohlhausen. A sketch by Island artist Stanley Murphy shows Mr. Bryant in a beret with arms folded and eyebrows raised, looking like a younger Marlon Brando.

A large spice rack in the kitchen betrays the couple’s love of cooking. “She does the pies and cakes and the esoteric European recipes,” Mr. Bryant said. (Ms. Kirchmeier’s parents immigrated from Bavaria.) “I cook all of the wild game and the fish.

“If there is one sin that’s created with cooking fish, it’s cooking it too much,” he added. He likes his game meat the same way. “When I cut the breast of the duck, I want blood pouring out.”

He looks forward to hunting every year, but not the “hundreds of people going through the woods screaming and yelling and shooting.” He opts instead for antique muzzle-loading season in December. “There are only a few who are willing to discipline themselves to use this type [of weapon], so I hunt during that period,” he said.

A spot on Mill Pond called Stepping Stones, where he first fished for trout with his friend Albion (Little Beanie) Alley, “has become a symbol of the birth of my rural pleasures,” he writes in his memoir. He also recalls surfcasting for bluefish and striped bass with his father in the 1930s using a long, tarred line attached to a cedar shingle stuck in the sand. He later upgraded to a simple rod and reel.

His adventures as a young boy were the subject of bedtime stories he told his children, through the eyes of a fictional character he called Mill Pond Joe. But committing the stories to print was a new experience.

While recalling simpler days, Mr. Bryant also takes a hard, honest look at his personal shortcomings over the years, revealing a life lived fully, if imperfectly. “It’s rambling, but I did that kind of deliberately,” he said. The rambling it does is the best kind, luring the reader in like a fish on a long line.

Mr. Bryant’s appetite for life runs deep. But as he admits in the memoir, it has gotten out of hand at times. He writes candidly about a 10-year love affair that contributed to the end of his first marriage after more than 43 years, and other regrets.

“A memoir is a difficult thing,” he said. “How much are you going to reveal?” In the end, he decided to change the names of his extramarital partners (there were three, in addition to shorter “flings”), although all have died.

“The hardest part was calling myself what I was — a horse’s ass — for cheating on my wife,” he said. “And the other hardest part was describing some of my family’s difficulties.”

“Alcohol has been a problem,” he said. “It was my father’s problem, it was my brother’s problem, it’s my problem.” After many years his drinking is finally under control, he said. “But Jesus Christ, it’s a little late in the day.”

The joys outnumber the sorrows in the memoir, but the sorrows are especially poignant.

He recalls the devastation caused by World War II, during which he parachuted into Normandy on D-Day, and into Holland as part of the largest airdrop in the war, despite having been shot through the chest in Normandy. He also fought in the Battle of the Bulge in the winter of 1944-45. On one occasion, a dying German soldier he encountered in the snow gave him a photograph of his sweetheart to return to her. “He watched me put the photograph in my pocket, then died,” he writes. “I lost the photo in the miserable days that followed.”

From his brushes with death during the war to his recollection of childhood antics, Mr. Bryant writes with the candor of a seasoned journalist and the imagination of a poet.

Soon after taking a small town in Germany during the Battle of the Bulge, his group came under fire from a lone machine-gunner. “Fingers of lead were plucking at my overcoat and gear,” he writes, and he dove into the snow with a fellow trooper. Miraculously, he was saved from serious injury by a metal container in his back pocket.

After the war, Mr. Bryant spent more than a decade as a managing editor — first at the Daily Eagle in New Hampshire and then at the Gloucester Times in Massachusetts. His career as outdoors columnist for the New York Times produced two published volumes — in 1971 and 1990.

The Times was a mixed blessing, he said. While it offered free travel throughout the United States and the United Kingdom, he was away from home for six months every year while his two daughters were growing up. “That’s hard on a young wife and a family,” he said. “It’s something to think about. In retrospect, I wouldn’t do it again.”

But journalism was also a great source of fulfillment.

“When I quit writing on a regular basis, I discovered that much of my emotional well-being was wrapped up in getting words on paper,” he writes. “Somewhat melancholic and guilt-ridden, I also had the notion that while assembling Mill Pond Joe’s history I might gain more understanding of his flawed and selfish, albeit life-embracing, behavior.”

In the final chapter, he writes of the comfort, in old age, of sharing his life and stories with friends and loved ones.

At age 92, Mr. Bryant still enjoys the outdoors intensely, although at a slower pace. He and Ms. Kirchmeier gather oysters in Tisbury Great Pond in the fall, or paddle along for a couple of miles, admiring the plants and birds along the shore, or stopping a while to fish for white perch.

From time to time, Mr. Bryant will get out his .22 rifle and shoot a white-tailed rabbit in his backyard, where he and Ms. Kirchmeier tend flowers, vegetables, fruit trees and other plants. He noted that one apple tree, now tall and moss-covered, was a gift from an ex-girlfriend about 20 years ago.

“This is its first good year,” he said, strolling through the yard. “They’re good apples.”

Comments (4)

Comments

Comment policy »