Thanksgiving when I was growing up always meant a different assortment of extended family members congregating at different homes, with no traditional format in place due to the realities of a modern and quite large brood of relatives. My parents divorced when I was young (I only vaguely remember them sharing the same roof) and there were a few years, which conveniently coincided with adolescence, when we ended up having multiple meals spread out over a few days. To a young, hungry boy it was the perfect way to feed my insatiable appetite, with my parents covering all the bases of familial obligations while my brother and I just did as we were told, knowing we would be well fed wherever we ended up. Football was the one thing that never changed for us. I am not talking about what has now become our national routine, for some percentage of the family to spend a better part of the day watching the NFL on television. Football in our family was different. We played football as a family, and age, sex or skill level made no difference. At least for a while.

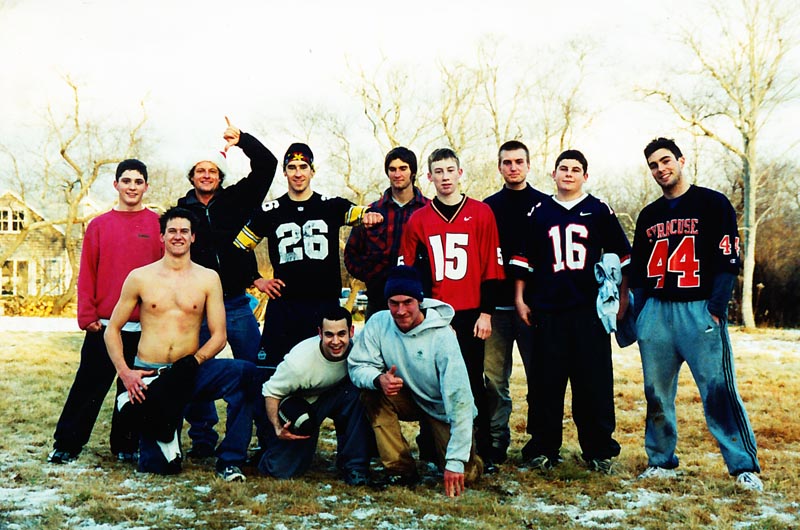

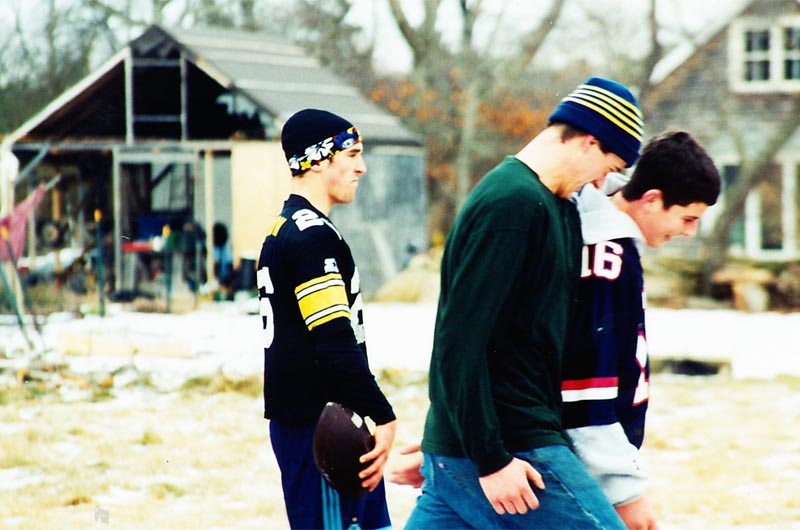

Our traditional family football games ended around the year 2000. What had started in the meadow at my Aunt Marie’s family property off of South Road as a casual and friendly way to burn a few extra calories before noon (and I believe at one point even involved a soccer match beforehand) had become an altogether different thing by the millennium. The team photo from our last game should shed some light onto how far things had gone. It shows a bunch of guys (no children) in mismatched football jerseys. Cleats are worn by all, as are tights and layers of warm clothes. We were basically one step away from holding a draft (we weren’t that far off in our system where game day captains selected teams on the spot in the style of a schoolyard), forming a players union and beginning random drug testing before reality set in about what was really happening. Before it all had ended, I had gone so far as to recruit the high school quarterback to play on my team. My siblings, cousins and I had all grown up (at least physically), and meadow football had traveled a good distance from where it began.

My first memories of the meadow are of the beehives near the far stone wall (later the back of one of the end zones, another safety infraction that was never addressed) that Marie tended during the summer season. By Thanksgiving her bees were put to bed for the winter and mostly dormant. As the football games grew and our skills developed, the hives became just another nuisance in our quest for glory, along with the piles of firewood on the far side of the opposite end zone, the bamboo grove that protruded further onto the field each season or the apple tree planted on the 20-yard line about 10 yards onto the field. The generally uneven turf filled with divots and ruts due to its nature as a meadow caused many a tweak early on, with one too many torn appendages resulting in surgery as the games continued through the years. One more catalyst to discontinue the games. The meadow would always be mowed prior to Thanksgiving, and discussion among family members leading up to the big day rivaled the ones other families have over preferred turkey cooking methods or travel plans. The meadow would be manicured to a different degree each season. Eventually the bamboo grove was eradicated, though there was a time when a team could rely on that grove for added protection from the end zone. One year my brother gave it the “twelfth man” award for its contribution to his team’s win at the awards ceremony, an event known to most other families as Thanksgiving dinner.

We eventually had to stop the madness. Testosterone and competition trumped the reason we started playing in the first place, the same reason one plays anything — and that is for fun. The bygone games we played ended up like gladiator matches, and so we no longer play. There are rumors that the next generation of our family is ready to bring the games back. Hopefully those of us who lived through the early years will be smart enough to police things a bit. I’m glad my family adapted, and now takes the time to walk on the beach or catch up with those who have travelled far and wide to get to the Island in pursuit of a hand-rolled pie crust.

And I’d like to suggest that these same principles of adaptation should be applied to Thanksgiving dinner. As Americans, we feel a sense of unity if everyone does the same thing. This is an obvious statement and powerful practice that applies to many decisions we make as a society. Having said this, Thanksgiving dinner has morphed into a cookie-cutter holiday that seems inflexible, at least on the subject of serving turkey to friends and family.

Turkey in America was first hunted, then crudely domesticated and is now produced so prolifically and quickly that supermarket chains can offer severely obese birds for as little as 50 cents a pound. With meat holding such merit on the table, symbolizing sustenance and wealth no matter how subliminally, the choice to serve turkey is basically made for us. Meanwhile, I haven’t been able to get through my day lately without another conversation about meat production or stumbling upon articles in major publications talking about our broken food systems. What am I getting at? Without boring anyone with grisly details about factory-raised birds, overuse of antibiotics or the environmental ramifications of conventionally raised poultry (information easily accessible with a simple Google search) let’s cut to the chase. You don’t have to eat turkey on Thanksgiving. It’s okay. It’s actually better than okay, it’s wise and responsible. A small number of turkeys were raised on the Island this year, their price tags making those who wouldn’t blink an eye to charter a plane to the Island question their value to me aloud, while even fewer wild birds were taken from our woods. I have never eaten a wild turkey, which makes me doubt its merit as a meal since I have eaten just about everything else growing up on this Island. Though Ben Cabot assured me this morning, as I gave him three quarts of lard from my freezer for his confit of wild turkey legs, they are far superior to store-bought birds.

This Thursday I think I will eat a squirrel, watch soccer and start a new tradition.

Comments (1)

Comments

Comment policy »