When the Old Whaling Church was dedicated in October 1843, Edgartown resident Ichabod Norton, age 81, was considered the wealthiest man on the Island. The whaling ship Iris was about to set sail from New Bedford for a voyage to the Pacific. First mate Richard E. Norton of Edgartown would keep the logbook for the trip, filling the pages with accounts of gathering sperm whale oil and watercolor pictures of a whaling hunt.

When Edgartown voters gather next week in the church for their annual town meeting, preserving town history will be among the items on the agenda. Mixed in with paving roads, Fourth of July fireworks and a new fire department jet ski are funding requests to restore disparate parts of Edgartown’s past: fragile old whaling logs kept by town residents; a portrait of Ichabod Norton by an Edgartown-born painter who went on to paint President Abraham Lincoln; and the tower of the Old Whaling Church itself, an architectural reminder of the Island’s whaling heyday.

Relics from the past, just like roads and fire department equipment, need updating once in awhile. These include the white tower of the Old Whaling Church, with its four-faced town clock that chimes out the hour.

“Time is starting to take a toll,” said Chris Scott, executive director of the Martha’s Vineyard Preservation Trust, which owns the church. “It’s a big wooden box that’s way up in the sky.” Rising more than 90 feet over Main street, the tower is exposed to wind and other weather elements.

The nearly 172-year-old church tower was last repaired about a decade ago, Mr. Scott said. Restoration is expected to cost $150,000 to $200,000. The town is being asked to fund $100,000 of that with community preservation money, and the preservation trust will pay the remainder.

Trim that’s starting to show rot will be replaced, Mr. Scott said, and the entire tower will be repainted. The most work and expense comes from building scaffolding to reach the tower. “Putting it up and taking it down in that location is expensive and tricky,” he said.

As a final touch, the four golden pineapples that have adorned the corners of the tower since 1843 will be re-gilded.

“I’m always impressed by that period of our history,” Mr. Scott said. While ships were being built that could spend years traveling the world’s oceans, people in the whaling era also brought Greek revival to the U.S. “They had more money than anybody in the country and they could pretty much do whatever they wanted. They weren’t constrained by budget, so they built this beautiful temple, kind of a scale model of the Parthenon in the heart of Edgartown,” Mr. Scott said, adding:

“I think people feel very connected to it. And almost everybody I talk to loves hearing the clock chime.”

While the Whaling Church and rows of captains’ homes on North Water street are everyday reminders of Edgartown’s whaling heritage, more fragile relics of that time are housed at the Martha’s Vineyard Museum in the form of about 125 whaling logbooks. The logs were used to record the important details of a whaling voyage: how many whales were caught and how many gallons of oil were taken, the longitude and latitude on a given day, and other goings-on aboard the ship.

The books are “among our most popular objects in terms of demand from researchers,” museum curator Bonnie Stacy said this week. The museum has identified five logbooks with Edgartown connections that are in need of restoration. Town meeting voters will be asked to spend just over $30,000 in community preservation funds for the project.

The books contain information about the whaling era that can’t be found anywhere else, Ms. Stacy said. “It’s amazing when you see how far these ships went. People from Edgartown, Martha’s Vineyard, went all over the world."

Museum education coordinator Ann DuCharme said the whaling logbooks are also “a gold mine” when it comes to educational programs for Island students. Students look at the artistic and informational pieces of the logbooks, she said, including stamps that were used to indicate when a whale was harpooned, or when one got away. Students also marbleize paper to mimic the front of the logbooks.

At the museum library this week, Ms. Stacy donned gloves as she looked through the logbook of the whaling ship Iris, kept and illustrated by first mate Richard Norton of Edgartown. There are detailed watercolor illustrations of whaling scenes: ships, a whale striking a whale boat, an island with palm trees. “You can see why people want to look at these all the time,” Ms. Stacy said.

But popularity comes with a price. “The things that are the best are handled the most and they get the most damage,” the curator said.

The five logbooks were sent for an evaluation at the Northeast Document Conservation Center in Andover, and reports outline what should be done for each of the logbooks.

The document center will use complex processes to repair each one. Pages will be vacuumed to remove mold, surfaces cleaned, pages washed in filtered water and ethanol, stains reduced or eliminated, tears removed, binding removed and restored. Some damage, like a splotch on the blue ink of the logbook from the Rose Pool out of Edgartown, might go back to the whaling days.

The restoration work could lead to future projects, including transcribing the logs. Digitization, though it is not part of this project, is another future possibility. One mottled brown logbook was kept aboard the whaling ship Erie from 1857 to 1862, with Jared Jernegan of Edgartown serving as the ship’s master. The book was brought home to the Vineyard and then repurposed. While the front of the log has entries in fine penmanship, later pages have been used as a scrapbook, with pasted newspaper clippings and other mementos. “It has merit as a record of a whaling voyage and it was a scrapbook that somebody kept,” Ms. Stacy said. “To preserve one, you have to destroy the other.”

While the scraps pasted in the book will be recorded, the whaling logbook aspect has been deemed more important, Ms. Stacy said. Part of the restoration work will remove the scraps and unveil what is beneath.

The logbooks are rarely displayed because of their fragility, though sometimes facsimiles are exhibited in their place. “But there’s really nothing like the original,” Ms. Stacy said. “When you actually see the physical volume, it evokes the day.”

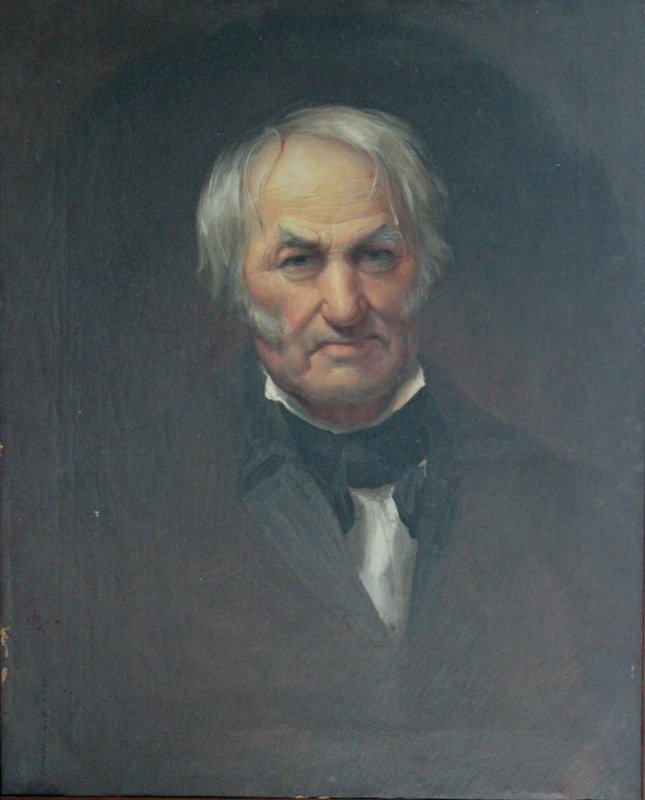

The museum also houses several paintings by Edgartown-born painter Edward Dalton Marchant. His likeness of Vineyard resident Ichabod Norton is in fragile condition, and the museum is looking for $3,400 in community preservation funds for cleaning and repair.

The painting likely dates to 1830, when Mr. Norton was about 69. The artist was about 24.

The painting will be displayed along with seven of his other works this Friday and Saturday for a mini-exhibit in the museum’s spotlight gallery. To get a look at the difference painting restoration can make, the Ichabod Norton painting will be displayed next to a Marchant painting of Dr. Daniel Fisher that was conserved a few years ago.

According to stories from Gazette archives, Ichabod Norton made most of his wealth from farming — he was said to have owned nearly 1,000 sheep — and later branched out into shipbuilding. He was a lifelong bachelor who was known as Uncle Ichabod. There was some debate after his death as to whether he was a generous man or if he had been stingy with his wealth. He died in June 1847 in Edgartown; his grave in the Westside Cemetery is marked by a large white marble monument.

Mr. Marchant, also born in Edgartown, went on to paint several famous men, including Henry Clay and President William Henry Harrison. He painted President Lincoln around 1863. But even at that moment, Edgartown was on his mind. “Seizing what seemed a few moments’ leisure one morning,” Mr. Marchant said, according to a Gazette article, “I told the president that I had a communication from the citizens of Edgartown, Martha’s Vineyard, the place of my birth, which breathed the warmest wishes for him and his administration. He requested me to read it, which I did. His gratification both in regard to the sentiments it contained, and the felicity of their expression, was most markedly evident.”

Comments (1)

Comments

Comment policy »