REFLECTIONS ON MARTHA’S VINEYARD: A collection of weekly essays by William A. Caldwell , published by the Vineyard Gazette from 1973-1986. Edited by Tom Dunlop. Vineyard Stories, Edgartown, 2015. 144 pages. Soft cover, $19.95.

He was a semi-pro football player as well as a boyhood farmhand, and he played piano for the silent movies at his hometown theatre in Hasbrouck Heights, N.J. He was among the most well-read of men, even though the drowning of his father in Lake George, N.Y., meant he had to leave high school his sophomore year in 1922 and go to work cleaning the bathroom and pumping the organ at the neighborhood Episcopal Church. He was a self-taught newspaperman from the age of 15 who won the Pulitzer Prize for commentary at 65.

In 1972, William A. Caldwell retired to a home on the Katama waterfront with his wife Dorothy after a lifetime working as a writer, editor and columnist for The Record of Bergen County, N.J. I must have met him three winters later, when I was 14. I had taken to hanging out at the Gazette office after school, watching stories get handed from the old Royal typewriters to the editors’ desks to the composing tables to the presses.

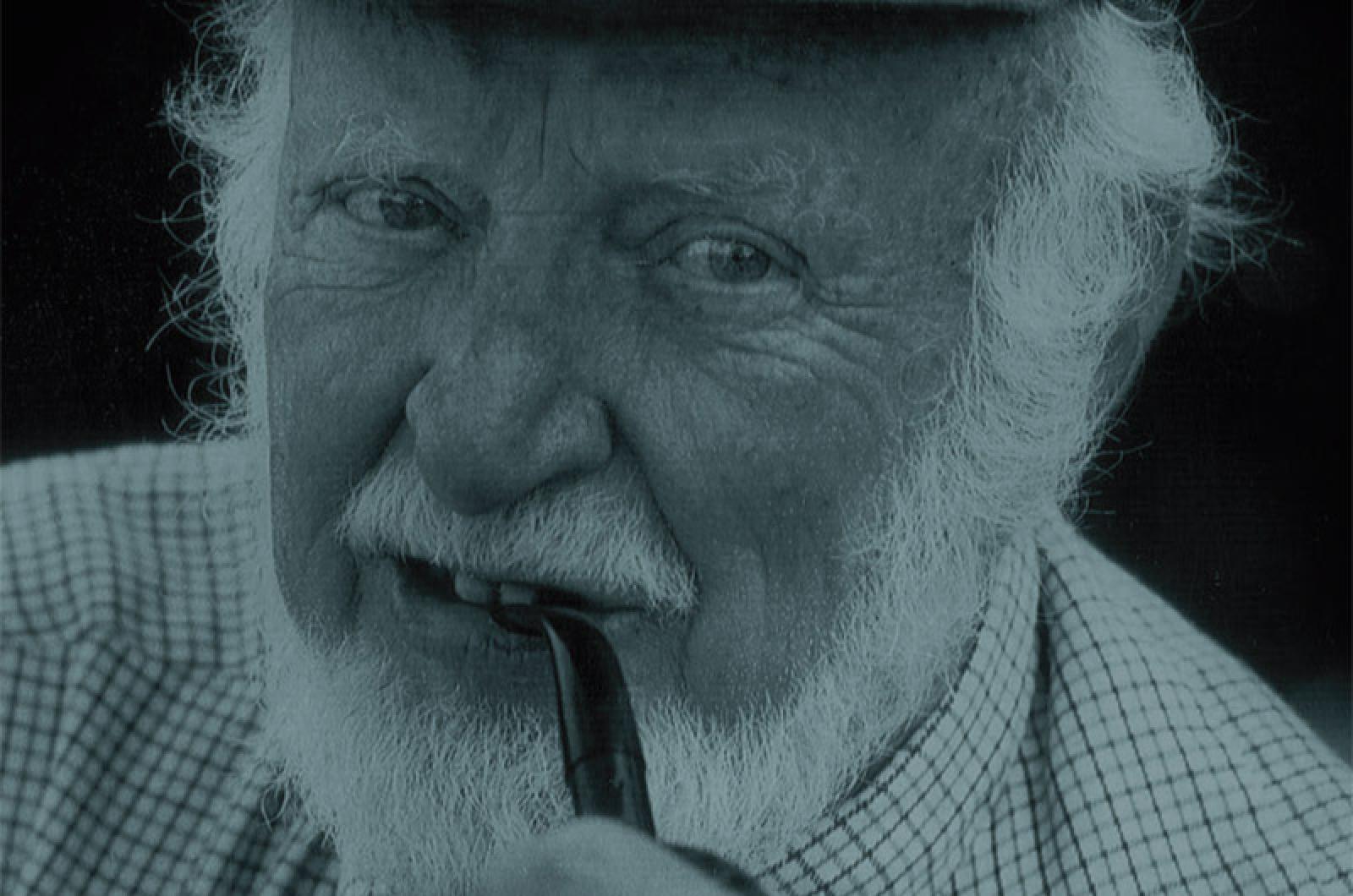

But I don’t actually recall meeting Bill Caldwell. He came to the office each week in a yellow Jeep CJ-5 to deliver his column to the editors. He was a skinny, white-bearded old man who wore a Greek fishing cap, smoked a pipe filled with apple-flavored tobacco, spoke with a slight stammer and then — one Friday in early February of 1976 — wrote a front page story about a great winter tempest that began:

“A windstorm that whipped shrieking gusts of snow and squalls of driven sand horizontally on gusts ranging up to ninety knots lashed Martha’s Vineyard this week through a day that felt like a season in Antarctica. Or hell. Then, having established who’s in charge around here, Nature next morning blandly invited Islanders to forget it. They won’t. For decades to come, grandchildren yet unborn will have to listen to ancients retelling the day of the tempest of ’76.”

Those five sentences hooked me. From that week forward, until his death in 1986, I read the weekly Caldwell essay, Reflections of That Man Friday, which ran beneath the drawing of a quill pen on the editorial pages of the Gazette. Somehow this spring, the honor fell to me to edit a book of some of the best of those columns and to reintroduce their author to a Vineyard audience that has not heard from Bill Caldwell in 30 years.

Fortunately, he does all the heavy lifting himself. All I need to do is offer you three bits of good news, all of it to be found in his writing.

First, for all the changes since then, the Vineyard that Bill Caldwell wrote about is emphatically and recognizably the Vineyard we know today. Also, whether we were born here or came from somewhere else, his essays carry us back to the Island when it was still new and thrilling to us, since he never stopped seeing and describing it – brilliantly – as a newcomer himself.

And finally, he offers us a bracing sense of optimism about the fate of Martha’s Vineyard and the world that surrounds it. Hopefulness was as rare a feeling then as it is now. But he loathed nostalgia, took heart from the wonders of a Katama sunrise, a courtesy offered in the middle of a traffic jam or the failure of a mean-spirited article to pass at town meeting.

Three minutes with a Caldwell column can arouse in the reader unaccustomed feelings of clarity, purposefulness and joy. He is worth getting to know again.

Some Noise about Stillness, July 12, 1974

By WILLIAM CALDWELL

It is 7:30 a.m., and here on the seaward deck of the house the silence is absolute.

One is peculiarly conscious of silence this morning. One has just returned from taking a wagonload of travelers to catch a boat. They are going to a wedding in New York. Here on the deck, silence, blessed silence, absolute silence. . . .

Just one moment, William. With one possible exception, which is somatic death, there is no absolute anything on the face of the earth. Right?

Wrong. It is now 7:45 a.m. I have been taking notes, and thus far I have identified twenty-two varieties of silence.

Three of them — no; counting the murmur of the sea along South Beach, make that four — are stillnesses of such low intensity that even when you call them to your attention you can’t be sure they’re there. One of these is what an engineer friend of mine calls the 60-cycle hum of the electric clock, the fluorescent bulb, the freezer. One is the presence of the megalopolis. A third is the Atlantic. The fourth, of which I hesitate to speak because there may be something pathological about it, is the pale toneless acoustics of one’s own body and mind. The flow of blood perhaps or of thin currents across the brain cortex, unheard, sensed only with an effort to screen out the other forms of silence.

That leaves eighteen kinds of stillness on my list, and we’d better get at them.

1. Deep in the Chappaquiddick woods a dog barked fifteen or twenty seconds ago. The concentric ripple of that phenomenon has been widening since. Dying, it just stirred the molecules of air around me.

2. In the dank windlessness the flag is scarcely stirring. It flops, limp on the pole, but the receptors in the skull certify that flop is what it does, as against flap or slap or flutter.

3. Away on the receding shoals the foraging gulls are mewing (the herring gulls) or hollering holp holp (the black-backed), and I am aware they had been silent only because I had decided not to hear them – had filtered the noise off the network.

4. Tock. A woody, hollow tock-tock. A gull has dropped a conch on Colonel Pfeffer’s asphalt and is now wrestling it up and down the driveway.

5. Come to notice, a whaler emits three quietudes: the engine, the harmonies of the sounding-board fiberglass hull, the whisper of water fore and aft.

6. That’s a robin. That’s a song sparrow. There’s evidence, says Dr. Gustav Eckstein, that birds can’t hear themselves. That’s a bobwhite.

7. The air pulses, throbs. A gull, flying low.

8. A honeybee, making local stops along the row of Rosa rugosa.

9. Two flies in three-quarter time.

10. A mosquito, invisible as well as inaudible.

11. Far down the harbor someone on a yacht at a mooring wants to come ashore for breakfast. How many times now has he sounded his horn for the service boat? You hadn’t heard them, but some computer in your skull answers: six.

12. A grackle is floundering in the birdbath. You can’t see the birdbath from here. How do you know it’s a grackle and how do you know it’s there? The grackle always says chuck when it lands in the birdbath. You didn’t hear it.

13. Wind is lisping in the pines.

14. On the pebbles small ripples are lapping.

15. A fisherman coming in from a night at Wasque just shifted his Jeep into second gear.

16. Someone within a mile of here is mowing his lawn.

17. The mainsail is crawling up the mast of the yacht moored off the point, a great white wet moth newly sprung from its cocoon. Silken stillness.

I am dealing with the question whether sound or anything else exists unless it is perceived, and I fear that I am in water too deep for safety, but we have yet to consider silence No. 18, and now I fear that I’m into allegory too shallow for satisfaction. Up to now we have talked of primeval matters mainly: wind and water and birds, animals and insects. Suddenly silence No. 18 became the thrum of engines, and there flitting through the tattered gray overcast was the Air New England plane from Nantucket.

On it came, the symbol of mankind’s dominion over earth and space and time, and the thrum became a resonance, the resonance a roar, the roar a thunder, the thunder a long shattering bellow.

One by one the small silences — or the frail filaments of perception — were swallowed into that hurrying hubbub until there was nothing left of the world for which the morning stillness spoke except the clamoring machine. Progress, or, the descent into the Inferno.

Poets and novelists try to avoid that kind of coincidence. It doesn’t seem to embarrass reality.

Comments (14)

Comments

Comment policy »