When Charlie Blair joined the crew working on Jaws in the summer of 1974, he had already crossed the Atlantic four times in a sailboat. The young captain had settled down on the Vineyard the previous fall after a major expedition, around the world, where an Island patron was in search of migrating birds and humpback whales.

But he didn’t anticipate the long days and nights he would endure the following summer, when a large crew of Hollywood filmmakers struggled against all odds to make a realistic-looking movie about a giant shark with a taste for human flesh.

At the time, Mr. Blair was an owner of the Ruddy Duck charter company in Edgartown, which the filmmakers had hired for a half day to help with their boats. “By the end of the day we were working for them,” Mr. Blair said. “And then the end of three days, I was managing all the small boats.”

“I worked about 21 hours a day and I slept in 10-minute catnaps everywhere,” he said. “On the sets, in the boats, on the pavement. I was one tired dude.”

But looking back, he said it was one of the best summers of his life.

The job included transporting as many as 200 crew members to and from their shooting locations off Chappaquiddick and South Beach. The Teamsters labor union in Boston was in charge of crew transportation, including boats, “but that only lasted a few days and they lost a lot of gear,” Mr. Blair said. “They got out of the boating business right away.”

Mr. Blair was one of many Islanders whose local knowledge helped make the film possible. Dozens of others appeared in bit roles and as extras, lending a real-world ambiance to the fictional Amity Island.

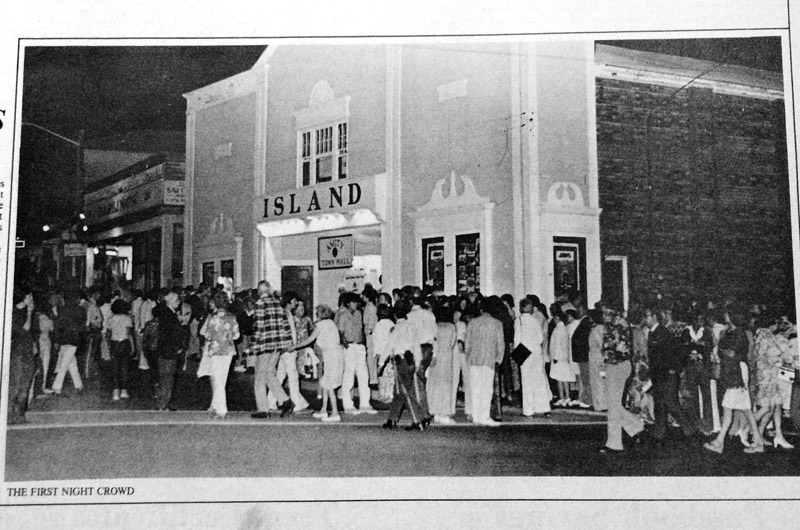

Forty years later, the world’s first summer blockbuster remains a treasured part of Island history. A screening Saturday at the Strand Theatre in Oak Bluffs marks both the 40th anniversary of the film’s release and the reopening of the historic theatre following its renovation this spring. The film will also show at the newly renovated Capawock Theatre in Vineyard Haven.

Jonathan Filley, a lifelong summer resident who was in college in 1974, remembers coming home and lining up a summer job at an Edgartown boat yard. Mr. Filley auditioned for the role of Tom Cassidy in the opening scenes of Jaws and soon found himself drunkenly chasing Chrissie, the shark’s first victim, over the dunes to go skinny dipping in the moonlight. He later encounters Chrissie’s arm on the beach. (The arm was actually that of Andrea Morton, who worked at the Kelley House and hid below the sand.)

After those scenes were shot, Mr. Filley landed a different job, working with Mr. Blair and others, providing support to the crew in whatever boats they could find. “You work a lot of hours,” he recalled. “You’d start at sunup and you’re going to just about sundown all summer long. It was a fairly grueling operation.”

Despite the local help, the crew still had to contend with changing tides and winds, and three mechanical sharks whose electric motors had to be replaced with pneumatic pumps that could operate in salt water. Shooting took three months longer than expected, and the film more than doubled its budget. Director Steven Spielberg has called it the hardest shoot of his career.

But the hardship is partly what made the film great, said Richard Paradise, director of the Martha’s Vineyard Film Society, which will host the screenings on Saturday. Without a shark early in the process, Mr. Spielberg was forced to rely on the power of suggestion, using underwater shots of arms and legs and allowing the primal, pulsing score by John Williams to work its magic.

“Part of the charm, part of the thrill, part of the mystery of Jaws is that it’s not perfection,” Mr. Paradise said. “Things were born out of necessity: the heavy emphasis on the unknown, the heavy emphasis on the music to create mood and tension and thrills.”

Jaws stayed in theatres well into the fall, he added, something rarely seen today. “People would go and see it over and over again,” he said. But few people anticipated how successful the film would be, and many questioned whether it would be finished at all.

“There were some very down days,” Mr. Filley recalled. “But the general mood was we had a job to do and we were doing it.” He added: “It’s really, really tough working on the water.”

In some of the later scenes, the shark is harpooned, with lines attached to floating yellow barrels. Instead of the shark, the viewer only sees the barrels racing through the water, or surreptitiously sinking beneath the surface. “It’s me on the other end in a Boston Whaler,” Mr. Filley said.

Much of the work was routine. Every day before sunrise, Mr. Blair would ferry out to Chappaquiddick to pick up Robert Shaw, who played Quint, the grizzled New England fisherman who would finally succumb to the shark, along with his boat, in Katama Bay. Mr. Shaw was an avid drinker, Mr. Blair said, but never missed a line. He also was one of the few to anticipate the film’s success. Mr. Blair recalled a typical pre-dawn conversation:

“Charlie, what kind of boat did they send you in today?”

“Well, Mr. Shaw, I’m in a twin-engine Mako.”

“How fast will it go?”

“About 50.”

“And how slow will it go?”

“Well, if we shut an engine off we can go about four.”

“Let’s go four.”

Edith Blake, an Edgartown resident, found herself pulled into the fray when joining her future husband Henry Beetle Hough, then publisher and editor of the Gazette, to a meeting with the filmmakers about a major beach scene they were planning to shoot on Chappaquiddick.

“I got up and I said, ‘That’s not going to work. You can’t get all those hundreds of people over there and back on a ferry boat. You are going to need to find another beach,’” she recalled. Soon she was working in the casting department and acting as a stand-in for Lorraine Gary, who played the Amity police chief’s wife. She also covered the entire production for the Gazette, and the next year published a book documenting the making of the film.

Robert Carroll, an Edgartown businessman and public figure who died this year, benefited greatly from the production. The Kelley House, for example, into which Mr. Carroll had recently poured a fortune, saw heavy business over the five months of shooting, and stayed open around the clock.

“He was terribly in debt,” Ms. Blake said. “And Jaws saved him.” Other businesses, including the Edgartown Paper Store, also enjoyed the surge in profits.

Mr. Carroll had a small role in the film as an Amity selectman, complete with some improvised lines, although most of that scene didn’t make the final cut.

“Spielberg was very good about hiring local,” Mr. Filley said. “For a lot of us that’s the fun part about watching the film 40 years later.”

In the beginning, many people felt besieged by the traffic and commotion around the Island, especially in Edgartown, where much of the shooting took place. And Amity itself was a somewhat unflattering version of the Vineyard, with snobby “Islanders” and a mayor who refused to close the beaches at the risk of losing summer tourism.

“The way the movie framed the Island, nobody seemed to think highly of that,” Ms. Blake said. “But the people who were involved in it loved it.” Similarly, Mr. Blair said the Hollywood crew had their reservations when they arrived. But by the final scenes many had found Island girlfriends and didn’t want to leave.

“It was party central,” Mr. Blair said.

Of all the media events on the Vineyard over the years, Ms. Blake did not believe that any have approached the level of excitement and disruption caused by Jaws. And Jaws changed people’s lives. Mr. Filley, for example, went on to a long and successful career in film and television production, managing films and among other things working as location manager for Woody Allen for years.

“The circus came to town and I ran off with the circus,” he said. “Because of Jaws I had a whole career. And I’ve had a great time doing it.”

With the money Mr. Blair made from his sleepless summer — about $50,000 — he headed down to Florida in his sailboat to compete in several races, including the Miami-Nassau Race, in which he won first place in his division. “So I had a good run with my Jaws money,” he said. He added that the popularity of Jaws had been a boost to his fishing charter business.

“I was leery about it but I think it really perked people’s interest in sharks,” he said. He also believed the Monster Shark Tournament in Oak Bluffs, a source of much controversy until it ended last year, was likely influenced by the success of Jaws.

“The impact of the movie continues every summer,” said Lee Fierro, former artistic director of the Island Theatre Workshop. Ms. Fierro played Mrs. Kintner, whose young son Alex (played by Islander Jeffrey Voorhees) was devoured by the shark. Ms. Fierro still gets fan mail from around the world, and believes Jaws will continue to thrill audiences long into the future.

She recently returned to the Island after visiting her two most recent great-grandchildren, one of whom she was delighted to find dressed in Jaws-themed rompers.

On the 30th anniversary of the release of Jaws, the Martha’s Vineyard Chamber of Commerce threw a huge party, called Jaws Fest, with appearances by Peter Benchley, author of the bestselling novel on which the movie is based, Susan Backlinie, who played Chrissie, Ms. Fierro and others. Michael Haydn, who plays guitar by a campfire in the opening scene, also appeared at the celebration, and will perform before each screening on Saturday.

“It should be winding down — the excitement — a bit,” Ms. Blake said. But she also noted the lingering echoes of those five months in 1974 that touched so many lives on the Island.

“Look around for Amity signs,” she said. “You’ll see a few.”

Comments (25)

Comments

Comment policy »