The chairman of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah) today announced that work will begin soon to convert a tribal community center into a gambling hall, despite a pending federal lawsuit aimed at determining whether it has that right on Martha’s Vineyard in the face of state and local prohibitions.

Responding to inquiries from the Gazette about increased activity at the site of the community center, tribal chairman Tobias Vanderhoop and tribal gaming corporation chairwoman Cheryl Andrews-Maltais said in separate phone interviews they hoped to have the casino open for business by the end of the year, if not sooner.

“As soon as possible,” said Ms. Andrews-Maltais, the former tribal chairman. “We are hoping to start offering our class II bingo in the fall,” subject to federal and tribal regulations and procedures.

Based on Mr. Vanderhoop’s testimony in a deposition for the federal lawsuit, and information that some preliminary work appeared to be underway, Aquinnah town counsel Ronald H. Rappaport early today had asked selectmen to meet in a special executive session Monday morning to consider the town’s options.

“I will brief them on what was said at the deposition and on information that I have acquired to date . . . . relative to moving ahead with the casino,” Mr. Rappaport said in a telephone interview.

He declined to characterize Mr. Vanderhoop’s deposition testimony, but said “these activities amount to a pretty clear picture that the tribe intends to proceed to convert the community building into some sort of casino.”

“I would add we are in federal court already arguing the very issue as to whether the tribe can do these activities in the town of Aquinnah,” Mr. Rappaport said.

Lawyers for the town, the commonwealth and the Aquinnah/Gay Head Community Association, which sued the tribe over its plans, most likely will alert U.S. District Court Judge Dennis Saylor about the tribe’s recent moves. Among their options is to seek a court order to halt any work until Judge Saylor rules on pending motions for summary judgment in the case, scheduled for argument next month.

“Whether these recent developments would lead us to such a request is still subject to discussion,” said Felicia Ellsworth, representing the Aquinnah/Gay Head Community Association.

Nevertheless, the decision to push ahead with work is bound to heighten tensions within the tribe’s membership, which approved a casino initiative in 2012 and nearly overturned it in 2014, and other opponents of the casino effort across the Island.

“I’m not opposed to gaming if it is done in a proper setting, but this is not the proper setting,” said Carla Cuch, a tribe member who co-owns a shop on the Gay Head cliffs with her sister Berta Welch. “Many tribal people feel this way as well.”

Another vocal opponent, Beverly Wright, said a petition has been circulated for another referendum on the casino at the next general membership meeting, possibly next month.

“Hopefully we will have a vote and the community center will not become a casino,” said Ms. Wright, former tribal chairwoman and Aquinnah selectman. “I would be for gaming too if it weren’t on Martha’s Vineyard, but not here, not on our traditional homeland.”

Flying in the face of assertions by the state and town of Aquinnah that their laws prohibit any such operation, tribal leaders said they have complied with appropriate federal law, especially the Indian Gaming Rights Act, and regulations that, in their view, trump any other concerns.

Mr. Vanderhoop said the tribe’s membership and government leaders have expressed a desire for the gaming facility. “And it is my responsibility to carry out the will of the people,” he said.

Scott Crowell, one of the attorneys representing the tribe in the federal case, said it is well within its rights to proceed with the project, despite the pending federal case. The tribe has been intending to move forward for more than a year, but has needed to comply with federal requirements and tribal requirements first, he said.

“To get into a question of when do you wait, when do you move, when do you wait, when do you move, as the chairman indicated, the tribe has the approvals required to move forward,” said Mr. Crowell. “And unless and until those circumstances change, we’ll move forward.”

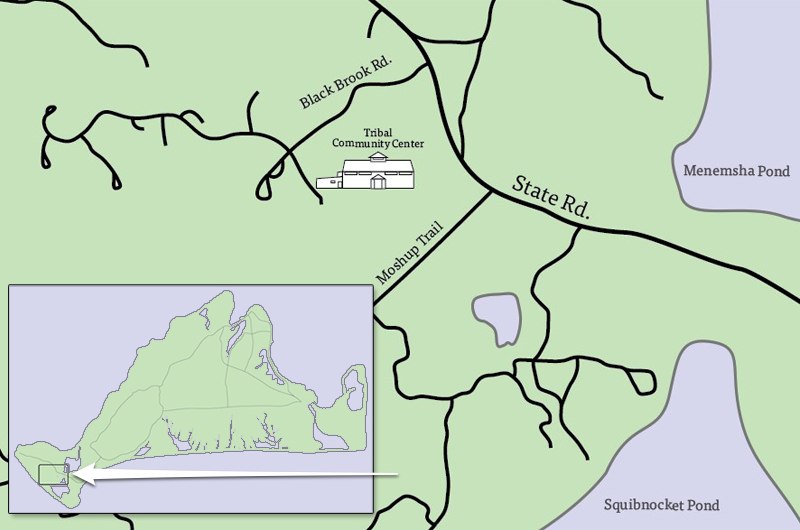

Although no construction work has begun, activity near the Community Center building appears to have picked up in recent days. The vehicle of a Connecticut-based company that has been involved in casino projects around the country was spotted alongside the building.

D’Amato Builders and Advisors of Norwich, Conn., has been involved with various Indian gaming projects in New York, Connecticut, and Oklahoma, as well as the Mashpee Wampanoag project in Taunton, according to an interview with the company’s founder published in U.S. Builders Review.

Ms. Andrews-Maltais said the tribe would use a company called Aquinnah Associates, composed of tribal members and experienced tradesmen, and also has a relationship with D’Amato Builders and Advisors.

Also, a classified advertisement appeared this week in the Gazette, seeking licensed electricians and helpers for a “10+ week commercial Aquinnah Casino project starting July 6.” The ad promises $2,600 per week for the electricians and $1,800 per week for experienced helpers.

After appearing on the newspaper’s website, the advertisement was canceled Thursday morning after two days.

And within recent weeks, the tribal council — a panel that includes the tribal chairman and 10 others — moved the project ahead by voting to authorize the change of use of the building from a community center to a casino, using its gaming subsidiary, the tribal chairman confirmed today.

Mr. Vanderhoop was elected tribal chairman in November 2013, defeating Ms. Andrews-Maltais, who championed the casino effort. Mr. Vanderhoop said today that he has favored the tribe exercising its federal right to have a casino, and the tribe has decided to do so in this case.

“The property has been transferred to the Aquinnah Gaming Corporation,” he said. “So they are making preparations to move forward with the project. Under the IGRA [Indian Gaming Rights Act] we have federal rights and the tribe has moved through the process to get all the appropriate [approvals] at the federal level to move forward. With previous votes of the citizens of the tribe, and tribal government, yes, we are moving.”

Before the announcement, tribe member and Aquinnah selectman Julianne Vanderhoop, who is also an Aquinnah selectman, expressed concern about the proposal and its impact on tribe.

“We know what gaming brings, and we do not want to see it in our community,” she said. “The people that stayed on the Island, tribal members, have a special sense of this land as our homeland. It’s very, very, very deep. And we do not want to see it destroyed . . .”

She and other tribe members indicated that the general membership had not been informed about the specific plans to move forward, a timetable for the project and a method to pay for it. Ms. Andrews-Maltais would not disclose the budget today but said she would at an appropriate time.

The high-stakes fight dates back at least to the 1970s when the tribe sued the town of Aquinnah (then Gay Head), claiming aboriginal rights to certain land within the town. In 1983, the tribe signed a settlement agreement with the state, the town and the Gay Head Taxpayers Association. It meant that about 400 acres of land would be transferred to the tribe, but it had to relinquish claims to other lands and waters. A key provision also required the tribe to follow state and local zoning bylaws.

The Massachusetts legislature signed off on the agreement in 1985 and Congress followed suit in 1987, with a federal law that said the lands were subject to Massachusetts state laws, “including those laws and regulations which prohibit or regulate the conduct of bingo or any other game of chance.” Earlier that same year, the Department of Interior recognized the Wampanoag Gay Head as an Indian tribe.

The next year, Congress passed the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA), which the tribe says supersedes the settlement and gives it authority for gaming. In 1999, the tribe tested that premise of state and town regulatory authority by building a shellfish hatchery on the Cook Lands without obtaining a building permit from the town. The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court rejected the tribe’s legal bid, saying the tribe waived its sovereignty under the 1983 agreement and must comply with town zoning laws.

But the tribe insists its authority has been affirmed by the National Indian Gaming Commission and by the solicitor of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. However, in an opinion the tribe requested from the Department of Interior in 1997, the Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs responded that IGRA does not grant the tribe authority to have gaming on its Aquinnah land, although it may seek a casino elsewhere.

A conversion of the community center to a casino would require the tribe to pay back a $600,000 U.S. Housing and Urban Development grant used to help construct the building.

The tribe broke ground on the building in 2004, but the building’s interior has not been finished.

Mr. Vanderhoop indicated that the days of calling the building a community center are now past.

“It has been repurposed, so it’s the former community center,” he said.

Alex Elvin contributed reporting.

Comments (21)

Comments

Comment policy »