Siamak Adibi was 17 when he left Iran and traveled 12,000 miles to create a new life in the United States. When he arrived unannounced at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore in 1950, the dean of the school was so impressed that he offered him a place in the premed program, on the condition that he complete a year at the University of Maryland to improve his English. The now-celebrated nutritionist and longtime Chappaquiddick resident never intended to write a book about U.S.-Iranian relations. But with everyday conversations so often drifting in that direction, he felt obliged to create a record of his life and political views to share with others.

For Iranians, he said this week in a conversation with the Gazette, the relationship between the two countries “is the most important issue of the day.”

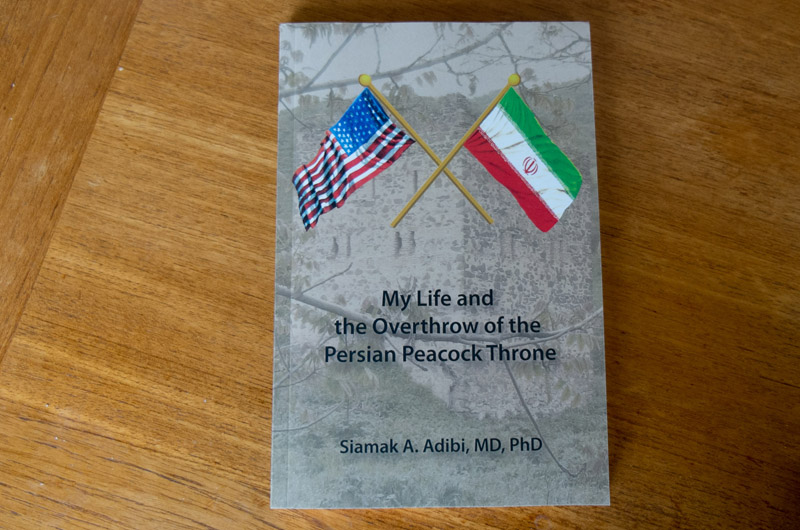

Dr. Adibi was deeply affected by the raucous politics of 20th-century Iran, a string of political coups and upheavals. His memoir, My Life and the Overthrow of the Persian Peacock Throne, was released in June, coincidentally just weeks before the United States and an international coalition brokered a nuclear deal that promises to lift sanctions on Iran and restore its economic relations with the West, while reining in Iran’s nuclear program.

“You cannot isolate a country to gain anything,” Dr. Adibi said Monday at his home on Chappaquiddick, one day before the deal was announced. “You need to have engagement. That’s what I’m asking.” But understanding the present requires understanding the past, he said, explaining the premise of the book. “When I was growing up, Tehran was a beautiful city,” he writes, recalling the “wide tree-lined boulevards under the shadow of the tall, snow-covered Alborz mountains.” The city harbored both Eastern and Western cultures, as reflected in its architecture, food and lifestyles.

Born in 1932, Dr. Adibi grew up one block from the House of Parliament in Tehran. His father, Sadegh Khan, whose own memoir is widely regarded in Iran, had helped install Reza Khan as prime minister in the 1920s. Reza Khan was soon crowned Reza Shah Pahlavi, later to be deposed during World War II, and replaced by his son, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.

Animosity between Iran and the west developed largely out of Western policies, Dr. Adibi writes, starting with Britain’s control of the country’s oil resources, and continuing with U.S. efforts to build Iran into a strong military ally to prevent the spread of communism in the Middle East.

Dr. Adibi draws inspiration from the reformist Mohammad Mossadegh, prime minister of Iran from 1951 to 1953, who attempted to nationalize the country’s oil industry. Dr. Adibi’s father was also a strong supporter, and the family home was a regular meeting place for Mr. Mossadegh’s National Front party.

Unlike Britain and France, the U.S. was never a colonial power in the Middle East, and when Dr. Adibi was growing up, “the Iranians were great admirers of America and considered it a good friend.”

But that all changed in 1953, when the U.S., under pressure from Britain, and from CIA director Allen Dulles and his brother, secretary of state John Foster Dulles, who feared the spread of communism, overthrew Mr. Mossadegh (a democratically elected leader) and returned the shah to power.

By then, Dr. Adibi was enrolled at Johns Hopkins, learning about American culture and medicine. It was years before he learned that Mossadegh had not simply fallen out of favor among the Iranian people.

Under the shah, Iran become more dependent on the U.S., which bolstered the country’s military, even promising nuclear capabilities.

Underlying Dr. Adibi’s plea for peaceful dialogue between the U.S. and Iran is his deep sense of loyalty to both countries. While opposing Islamic rule, he owes much of his success to the shah, who financed his American education. “He helped me greatly,” Dr. Adibi said. “But he had become a serious dictator because of American influence.”

After finishing his medical training at Harvard and MIT in the 1960s, Dr. Adibi and his wife, Joan, built a summer home on Chappaquiddick, where they have lived part-time for more than 50 years. The modern, sunlit house is filled with abstract paintings, including several by their daughter Elise Adibi. Other family members are scattered around the world, including a niece and brother in law in Iran.

Dr. Adibi composed his memoir entirely by hand on Chappaquiddick and in Pittsburgh, where he practiced medicine for 40 years. The manuscript was transcribed by his former secretary Mary Ann Krupper, and edited by Mrs. Adibi.

Despite his love for Iran, Dr. Adibi has no plans to go back. He recalled the period in the 1970s when the shah had launched a campaign to modernize the country, including through expanded health care services. Dr. Adibi was summoned to be the imperial medical chief, but the presence of a Western-educated physician in Iran was not entirely welcome.

“I got caught between the extremists and the reformers,” he said.

During a popular uprising in 1978 — largely the result of the shah’s neglect for conservative Muslims — the shah was deposed and Iranians lost many of the social freedoms they had enjoyed under his rule. Dr. and Mrs. Adibi were at home in Pittsburgh, planning their move to Iran, when the news came.

With the return of the exiled Ayatollah Khomeini, many non-Muslim Iranians were either killed or forced to emigrate. Dr. Adibi’s own family members, some of whom had held government positions, had to quit their jobs and destroy all evidence of their ties to the shah.

Fearing another U.S.-led coup, Mr. Khomeini helped foster a strong anti-U.S. sentiment in Iran.

“There is no open society in Iran,” Dr. Adibi said. “They can only express a desire to have an open relationship with America . . . . These are the upper class, educated people of Iran.”

Relations deteriorated further during the Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s, when former Iraqi president Saddam Hussein, whom the U.S. had supported, launched a major chemical weapons attack on Iran, killing thousands. That set the stage for violent anti-American groups to form throughout the region.

Over the decades, both Iran and the U.S. have acted poorly, Dr. Adibi said. But he hoped both countries could put the past behind them. He sees the nuclear agreement as an opportunity for new policies and trade opportunities that Iranians desperately need. “This is a fantastic deal for both countries,” he said.

He also believed that Iranian president Hassan Rouhani, whose election in 2013 raised hopes for a more open society in Iran, was sincere in his commitment to the deal.

“The point is we really have no choice,” he said. “You only can really resolve animosity with dialogue and talking to each other and making trades.”

Despite the mistakes of the last six decades, he believed improved relations with Iran could still benefit U.S. interests in the region. “This is the most stable and the most powerful country in the Middle East,” he said. “And with all the problems we have in the Middle East right now, we need an ally.”

Comments (10)

Comments

Comment policy »