At Robert Peace’s funeral in the spring of 2011, friends and family celebrated his life by telling stories. Even after the funeral, the stories continued — on Facebook, on the phone and in the many communities where the young native of Newark, N.J., had left an impression.

Jeff Hobbs was Rob’s friend and his roommate at Yale, where both men graduated in 2002. But it wasn’t until Rob’s violent death, in a basement apartment surrounded by marijuana, about a mile from where he grew up, that Mr. Hobbs began to glimpse the full arc of Rob’s life, from dangerous city streets to the halls of the Ivy League, and later to a somewhat directionless life selling pot in Newark.

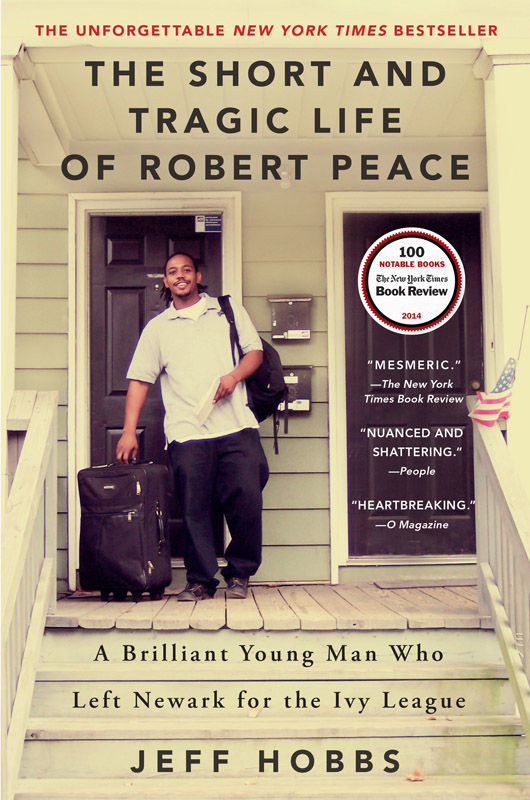

The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace, released last year to wide acclaim, is Mr. Hobbs’s memorial to Rob’s life, telling the story from birth to death in obsessive detail and a clear, heartfelt narrative. It started with a series of private essays about guilt and friendship. But Mr. Hobbs wanted to create something more, he said in a conversation with the Gazette, “something better than an obituary, to remember his life as opposed to his death.”

With the blessing of Rob’s mother, Jackie, the young author embarked on a three-year journey into Rob’s world, conducting hundreds of interviews in kitchens, cars, offices, on front stoops and while walking the streets. He amassed about 1,300 pages of transcribed interviews, before finally sitting down to begin writing the book.

Mr. Hobbs will speak on Saturday at the Harbor View Hotel at 1:30 p.m. and in Chilmark on Sunday at 9:45 a.m. as part of the Martha’s Vineyard Book Festival. His speaking tour, which coincides with the book’s release in paperback, includes locations on the East and West coasts. He currently lives in Los Angeles with his wife and two children.

Rob’s story is a window into a version of America that many choose to ignore. He was born into a poor family in a predominantly African-American city. Both his parents struggled to make ends meet, and his father sold drugs to supplement his meager wages. Rob’s mother knew that drugs and family don’t mix so she chose not to marry his father.

By all accounts, Rob reflected the best qualities of both his parents — his father’s sharp intellect and gregariousness, and his mother’s independence and empathy. The adults at Rob’s day-care center half-jokingly called him the Professor. In high school he earned consistently high marks, while working part-time jobs. At Yale, he continued to excel, but was also selling large amounts of marijuana brought in from Newark. By the time he graduated he had saved more than $100,000.

Throughout his young adult life, Rob carried a heavy burden. Before he turned 10, his father was convicted of murder, after a years-long legal process apparently riddled with flaws. Despite his continued success academically and an active social life, Rob didn’t share this secret with anyone until his final term at Yale.

In preparing to write the book, Mr. Hobbs would often spend weeks at a time in Newark, building a network of friends and acquaintances and gradually widening his orbit. The storytelling depended largely on cross referencing various accounts and finding the most accurate versions to shape the narrative.

“It was clumsy, it was comical,” the author said of the process. “Obviously, I’m a white guy in a neighborhood where that’s not very common most of the time. So it was uncomfortable at times. Harrowing once or twice. But mostly it was just a lot of grief and a lot of laughter.”

The orbit widened to include people he might never have met, including some of Rob’s high school friends who sold drugs and had been widely blamed for Rob’s murder. On one occasion, Mr. Hobbs found himself staring down the barrel of a gun in the house of a drug dealer in Philadelphia late at night. “But that was sort of my own fault,” he said, explaining that the dealer had only a remote connection to Rob and his circle of friends.

Preconceptions were sometimes shattered. Mr. Hobbs remembers calling up Rob’s high school friend Flowy (one of those held accountable for the murder) after arriving at the wrong address for an interview. “Get back in your car, lock your doors, stay on the phone with me because you are in a very bad neighborhood right now,” Flowy had advised.

“This was a guy who loved Rob, and certainly not a villain,” Mr. Hobbs said. “The heart of this story is that the lines that we like to draw are not as clean in real life.”

As an introvert, Mr. Hobbs tends to spend a lot of time in his garage with a notebook, he said. “So it was valuable to just be out in the world.” He was awestruck by the amount of effort people made to help bring Rob’s story to light.

But the greatest reward, he said, has been the opportunity to visit schools around the country and share Rob’s story. The book focuses largely on the social isolation that many students at Yale experienced, perhaps Rob most of all. “Every single one, once the topic came up, expressed this trauma of isolation that still trails them 15 years after college,” Mr. Hobbs said. “These were people I knew and I just had no idea of that struggle. And they didn’t want me to have any idea because that signals not belonging.”

Despite his many dorm room and dining hall conversations with Rob over the years, Mr. Hobbs never quite broached the topic of Rob’s father, something he still regrets. “I couldn’t have changed anything,” he said. “But if many people had been willing to ask the question and listen to Rob’s story it might have turned out differently.”

“That vulnerability is really hard,” he added. “Not just to tell it, but also to hear it.”

The problem of social isolation spans the entire educational spectrum, he said. His next book will focus on issues surrounding primary schools in Los Angeles. He hopes students can learn to appreciate that everyone’s story is different. “It’s really an issue of awareness,” he said. “Just being aware of what the person sitting across from you might be experiencing.”

Comments

Comment policy »