Ginny Gilder is a self-described challenge seeker. As a young woman, she set her sights on a goal that most told her was impossible — to become an Olympic medalist in rowing. Her family had broken up when she was a teenager and she struggled with asthma. But despite the odds — and the put downs — she became a silver medalist at the 1984 Olympics.

Later on she began a successful business career as co-owner of the Seattle Storm, a professional women’s basketball team. Then she decided to confront a new challenge — writing a book.

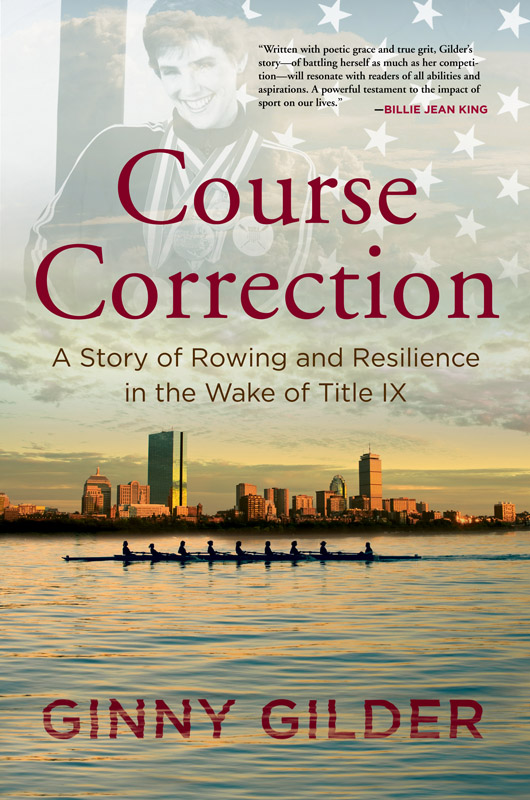

“I wanted the intellectual challenge of trying to write something that was not just interesting but also well written,” she said of her new memoir, Course Correction.

The author will take part in the discussion Women and Sports: On the Field and in the Media at 9:30 a.m. on Saturday at the Harbor View Hotel and will speak at the Chilmark Community Center on Sunday at 9 a.m.

Course Correction is as much a story about overcoming adversity and dealing with grief as it is about following one’s heart. Her unrelenting drive is perhaps her most defining characteristic, but throughout her college years self admonishment earned a close second place.

Ms. Gilder entered Yale University in 1975 as a novice rower and trained hard to eclipse more seasoned athletes. “The upperclasswomen fretted about the onslaught of winter training — something about difficulty and intensity — but I nodded happily at their grumbles about weightlifting, running, ergometer pieces, stairs, circuits,” she writes in Course Correction. “I didn’t know what they were talking about, but by now the unfamiliar was no deterrent. I would be there, come hell or high water. Ignorance was bliss.”

The women’s rowing program at Yale, like most women’s sports at the time, did not have a lot of support.

“Athletic competition builds character in our boys. We do not need that kind of character in our girls,” declared a Connecticut judge at the time, rejecting a high school girl’s petition to join a boys’ indoor track team because there were no girls teams.

Inadequate facilities for female crew led to illness in the winter months, as they sat, soaked and shivered on long bus rides back to campus after practices. Their male counterparts had access to showers at the Robert Cooke boathouse, and in a protest that garnered international media attention and ultimately shamed the University into upgrading its facilities for women, the women’s crew team entered the office of Joni Barnett, Yale’s director of physical education.

“Perfectly synchronized, we turned our backs to the administrator, pulled off our sweatshirts, dropped our pants and stood stark naked, absolutely silent,” writes Ms. Gilder. They had Title IX written in marker on their backs, and were trailed by Yale Daily News staffer and stringer for the New York Times, David Zweig and photographer Nina Haight. “These are the bodies Yale is exploiting,” read Chris Ernst, the team’s captain, from notepaper during the demonstration.

In an interview with the Gazette, Ms. Gilder remarked on the sorts of biases women in sports still confront. She referred to the criticism of tennis champion Serena Williams’s body noting: “You would never see an article about how a guy looked or about what he thought of his body — never. In 2015 I do not understand how we have such a rigid definition of what femininity is in a world where we are considering gender in a more fluid way,” she said. “I am confused by this idea that women are still being pegged into such a narrow slot.”

Challenges she overcame personally in the 1970s have since become contemporary societal battles and debates.

“I really wrote this book with the hope that maybe it would help other people be able to look at their lives a little differently,” she said.

Ms. Gilder makes a comparison between rowing and her ability as a writer.

“Much like rowing, writing takes time and is certainly something that takes practice,” she said.

Comments

Comment policy »