Familiar images of police violence flashed across a giant movie screen at the Martha’s Vineyard Regional High School last Wednesday, where hundreds of people gathered for this year’s forum hosted by the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice at Harvard Law School.

Black and Blue: Policing the Color Line featured two panel discussions with leading activists and public figures, along with music, poetry, and film clips from What’s at Stake, a new project by Black Entertainment Television that explores issues important to young African Americans.

Following the deaths of Michael Brown, Freddie Gray and others at the hands of police in recent years, the forum placed the recent protests in Ferguson, Baltimore and elsewhere into the broader context of the civil rights movement, and looked ahead to the future.

At the start of the afternoon, the audience stood and joined singer Michelle Holland and pianist Frank Wilkins for a performance of Lift Every Voice and Sing, often referred to as the black national anthem.

The first panel, Policing the Color Line, explored the problem of police violence and the underlying policies and examined the importance of cooperation among the various actors in the struggle for criminal justice reform.

Panelists agreed there was nothing new or unique about police violence. Many pointed to the need to understand the historical context of the recent incidents, and to confront the underlying policies that continue to disadvantage African Americans.

Moderator Steven Hawkins, executive director of Amnesty International USA, opened the discussion with a question for the five panelists: “Is this just a moment that we are passing through, or is this an opportunity for movement building?”

Ras Baraka, mayor of Newark, N.J., saw things in a slightly different light.

“It’s obvious that this is not a moment in time,” he said. “This is not a time for a movement. I think that saying that disconnects folks now from the historical struggle that has been taking place for a very long time in this country.”

He also stressed the importance of learning from those who struggled in the past. “All of these things are part of a larger movement,” he said.

But Raj Jayadev, founder of the Albert Cobarrubias Justice Project in San Jose, which helps to empower families swept up by the criminal justice system, saw a major shift in how movements are being built. He drew attention to the many people with no experience in activism whose lives have been affected by police violence and are now taking a stand.

“It’s going to change the future of this country forever,” he said of those efforts.

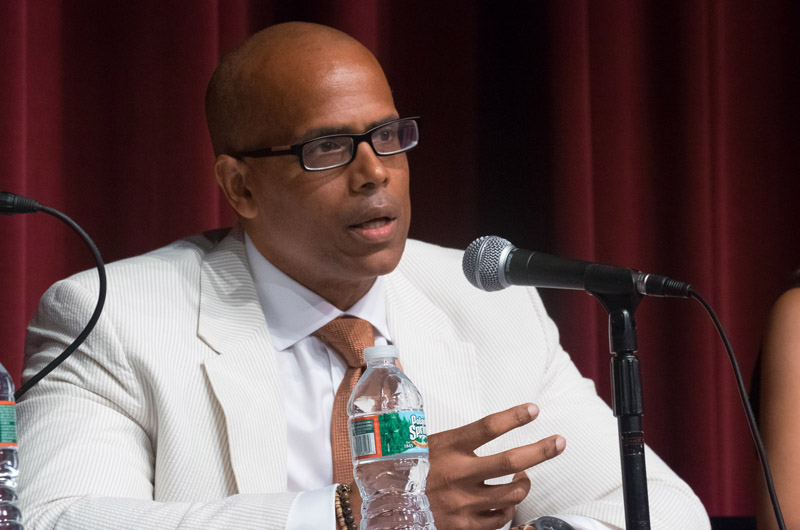

BET news correspondent Marc Lamont Hill agreed with Mr. Baraka that the past should not be forgotten. But he also pointed to “a new iteration” of the ongoing struggle.

He compared the death of Michael Brown in 2014 at the hands of a white police officer to a public lynching or the murder of Emmett Till 60 years ago next week. The difference was that people videotaped Mr. Brown’s body, which was left in the street for at least four hours, and the videos were seen by millions.

“Suddenly the world said: Wait a minute, what’s happening,” Mr. Hill said. Young people have since “rummaged through history” and are using some of the same tactics as the early civil rights activists, he added, but deploying them through modern technology.

Much of the conversation focused on the need to appreciate different roles in the struggle. Mr. Baraka used the analogy of a bus trip, where many people working together get the bus to its destination. People often fail to see the full picture in all its complexity, he said: “If you believe what you are doing is the answer and not a piece, you will never get there.”

Lisa Thurau, founder of Strategies for Youth, which provides training to improve police interactions with young people, noted that the police are “the start of a horrendous, long death march for too many people.” In many cases, arrestees are unable to hire a lawyer or post bail for minor offenses and end up in jail by default. Ms. Thurau lamented the lack of communication and mental health training in many police departments.

She agreed that everyone needs to work together to bring about reform.

“There are many ways to get down a hill,” she said.

Mr. Baraka noted that many people in his city do in fact appreciate the police presence in their neighborhoods and schools. Fixing the criminal justice system will require looking honestly at all the pieces, he said. “It’s going to take all of us together.”

Panelists discussed the lack of police data regarding arrests, which attorney Marcellus McRae argued could itself be illegal since it inhibits reform and contributes to the suffering of minorities. Mr. Hill noted the criminalization of drug addiction and homelessness, which he said has created a penal state and fueled the cycle of poverty.

He warned that the system itself may be inherently unable to produce justice, and urged people to rethink the language they use to talk about the problem.

“Mass incarceration implies that everyone is being incarcerated,” he said, but most are black males. He also noted the 20-minute safety checks many kids have to endure before entering their schools, and suggested “pushout” as an alternative to “dropout.”

Mr. McRae said in closing that racism will not end overnight. “What do we do in the interval?” he said. “That can be a long, long, long time.” He urged people to join the long haul but also focus on shorter-term goals.

The second discussion picked up on that same thread, looking toward the future.

The five panelists focused largely on the power of narrative to both oppress and to liberate. Artist-activist Daniel Beaty, who opened the panel with a poem about his incarcerated father, drove the point home.

“Narrative is at the root of everything,” he said. “If you want to oppress a people you tell a story, you craft a narrative that justifies the systems of oppression.” But the other side of the coin is the need for people to feel safe sharing stories their own.

DeRay Mckesson, a Ferguson activist and organizer, said that one defining feature of the current moment is that people are sharing their stories to mobilize against oppression. But he also worried that the stories themselves may not affect those in power.

Bithiah Carter, president of New England Blacks in Philanthropy, said that prior to the recently publicized police killings, many African Americans with comfortable lives had come to believe that more had changed since the 1960s than was the case.

“We have allowed media and others to control our history,” she added. “How do we tell our stories? How do we take control of our stories?” She later suggested creating a “black public square” to help bring the various efforts together in a safe space.

Mr. Beaty further emphasized that stories could make the struggle more accessible to people for whom other aspects of the conversation may not resonate.

But not everyone turns inward in times of trouble. Justin Hansford, a professor at St. Louis School of Law, argued that some in power had woken up to the criminal justice problem in Ferguson and Baltimore only after people began destroying property.

“The danger is, when we come to the table, are we going to be able to stay in a relationship with those people so that we can proclaim that we are speaking on behalf of the group that is our constituency,” he said.

The group also explored the topic of success in the context of continuing struggle.

“We have not yet won anything,” said Mr. Mckesson, arguing that a narrowly defined goal would allow protesters to know when they had won. But Angela Glover Blackwell, CEO of PolicyLink, a national research and advocacy group, argued that multiple goals should be pursued at once. Focusing on the moment is important, she said, but so is transferring that energy to the next phase, which may rely on different people with different skills.

“If there is a lull you are dead,” she said. “It has got to be seamless.”

The forum ended with Ms. Holland and Mr. Wilkins performing Someday We’ll All Be Free by Donny Hathaway. Guests mingled in the lobby of the auditorium, browsing books for sale and catching up with friends before heading out into the warm afternoon.

Comments

Comment policy »