How do you go about fix ing a whaling logbook damaged centuries ago by water? It sounds odd, but among the first things an expert might do is soak the afflicted pages in yet more water.

Yes, the water in the laboratory might be more scientifically applied to the pages than a great wave crashing wildly over the deck of a ship in the middle of the Pacific, or spilling from a jug below decks. The water might also be filtered for purity, for instance, and flavored with alkaline to raise the pH level and reduce the acidity of the paper so that it doesn’t turn brittle afterward.

An artisan in the lab might then find herself changing the bath of fresh water over and over as the acid floats off the page in broths of yellow. And yes, for sure, she’s going to check the ink on the page beforehand to make sure it won’t dissolve from the page as well, erasing forever the voyage of the whaling ship whose story she’s trying to recover and save.

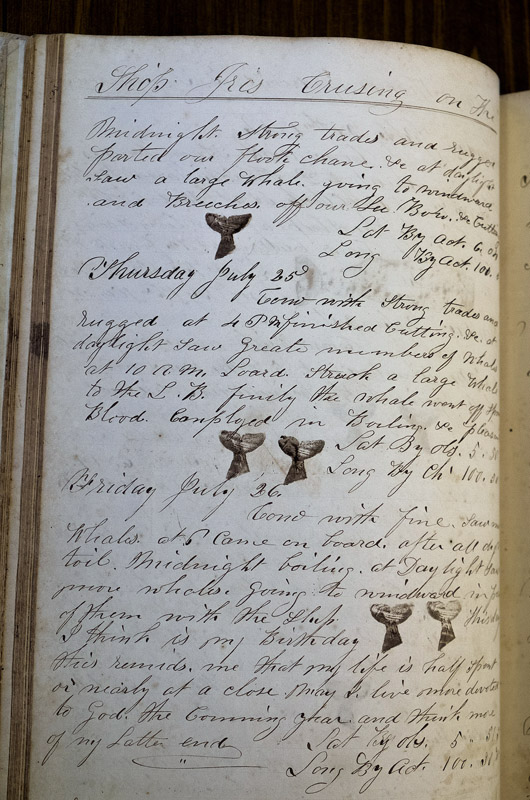

The injured page, photographed before and after, appeared on a screen at the Harbor View Hotel on Tuesday evening. Kristi Westberg, assistant book conservator at the Northeast Document Conservation Center in Andover, pointed out that the watery damage done so long ago — spreading darkly along the top of the page like the imprint of a wave along a beach — was much fainter after the treatment.

“Those distracting water stains have kind of faded into the background now,” Ms. Westberg told an audience of about 50 people. “But also I like that they still remain. There’s over-treatment that you could do to get those to completely fade way. But remember, they’re logbooks that were on whaling ships, so the fact that it was damaged by water is part of its story, and we don’t want to erase that. So you can still see the water damage. . . . It’s just not distracting you when you’re reading it.”

The Harbor View event celebrated the return of five whaling logs to the Martha’s Vineyard Museum after four months of conservation work this summer. All five logs, dating back to the early or middle 1800s, are associated with ships or captains or officers or crewmen who hailed from Edgartown during the most profitable period that Vineyard whaling ever knew. The cost to restore the logbooks amounted to $30,000, an expense recommended by the Edgartown Community Preservation Committee and approved at town meeting this spring.

The museum archives nearly 150 logbooks, and a survey by Insley Julier, an archivist, identified the five Edgartown volumes and seven others associated with different Island towns as being most in need of repair and conservation. After the funding was approved, chief curator Bonnie Stacy sent the five Edgartown books to the conservation center. Repaired and conserved, they were presented to the public in specially constructed archival boxes for the first time at the presentation on Tuesday evening.

To a layman, the damage, as shown on screen, looked almost insoluble. Some of the problems were caused by the perilous environment in which the logbooks traveled, others by people handling them during the voyage. “So there’s water, there’s mold from the water, there’s salt, there’s lots of pests on a ship, there’s bugs as well as maybe rats and mice,” said Ms. Westberg. “Then there’s just the general movement of being on a ship, and because it’s a logbook, it’s something that got handled daily.”

Even after they came ashore for good, the five logbooks faced trouble, good intentions notwithstanding. Bindings were clumsily mended with tape. Children were allowed to draw on unwritten pages. And in the case of the logbook for the 1857-1862 voyage of ship Erie, commanded by Capt. Jared Jernegan of Edgartown, someone actually converted it to a scrapbook, gluing newspaper columns — mostly inscrutable lists of names and places — over the original text. Then they decided to try to undo what they had done by peeling the columns away, which was even worse.

“We humans want to fix things. Somebody tried — I’ll give them that,” said Ms. Westberg.

Using ultraviolet light, the conservation center managed to reveal much of the text that was either under the clippings or mostly lifted off the page during the clumsy removal effort. Ms. Westberg cleaned the surface of each page with vulcanized rubber, then bathed and lightly brushed them to lift away the newspaper columns (which were also saved as part of the historic record).

“Next, they were mended with Japanese tissue and wheat starch paste,” she said. “We used Japanese tissue because Japanese papers are made with really long fibers, and so that means even if the papers are really, really thin, they’re really, really strong. But they still remain flexible.” The pages were re-sewn to the spine with linen tape and thread. The wheat starch paste was used so that future conservators can remove the adhesives again if better techniques come along.

The pages of the logbooks associated with Edgartown have all been digitized, thanks to a $6,000 contribution from the family of Joan Rosé Thomas, the great-granddaughter of Richard E. Norton of Edgartown, an officer who wrote the entries and painted the dramatic watercolors of hunts and whaleboat wrecks found in the especially prized logbook of the 1843-1847 voyage of the Iris, donated to the museum in 1968.

Ironically, the work to save the five logbooks has been done, but no one yet knows what they actually reveal about the voyages they record. The museum does not now have the resources to transcribe the many whaling volumes it has in its archives. But with these specific journals digitized and soon to be posted online, it will be possible for volunteers to do that work, even from home.

“We may have crowdsourcing transcriptions,” Ms. Stacy, the curator, told the crowd. “There are many fun things that we might ask you to do.”

Comments

Comment policy »