In 1988, Donald Herman and his wife Pamela and their 20-month-old son Eric moved from Savannah, Ga. to Martha’s Vineyard for him to serve as head football coach and teach physical education at the Martha’s Vineyard Regional High school for one year. Twenty-eight years later, Coach Herman is still here. Last year, he was inducted into the Massachusetts High School Football Coaches Hall of Fame. But this year will be his last as a coach and teacher.

“Run!” Coach Herman bellows to seven students who are enrolled in one of his gym classes. Coach Herman is tan, trim, and as he says, “5’4” on a good day.” He stands barefoot on the side of the school’s track wearing gray athletic shorts and a bright blue Asics T-shirt. He is barefoot because he had to wade into several giant puddles on the football field to remove drain covers.

“Hopefully, the puddles will go down by practice,” he says.

But right now, his main focus is on these seven students in his strength and cardio class, one of the five physical education classes he teaches on a weekly basis. Today, he has taken the students outside with co-teacher Alyssa Lemoi to the school track to do intervals of walking, jogging and running.

“This track and field didn’t used to exist,” he says. “It was all woods back here. When we first started using it as a field, we’d find things like muffler parts.”

He checks on the students. “Run!” he yells. The students begin to trot. “RUN, not jog!” he yells louder. A few speed up, but after six rounds of running as fast as they can for a minute and a half, most are spent and drag their feet in a slow jog. One girl gasps: “How much time do we have left?”

Coach Herman smiles. “Enough. Keep going. We’re almost done. Let’s go!”

“I am a firm believer in conditioning,” he says.

After instructing a cool down, Coach Herman has mercy and walks his class back inside. As they head for the locker rooms to change, phys-ed department chairman Kathy Perrotta calls out to him.

“Coach Herman do you have a minute?” All students and staff call him Coach Herman.

Back inside the school, he dismisses his class and then stands in the hallway, greeting and talking to students as they move through the hallway. He seems to know everyone. When the halls empty, he walks to his office in the boys’ locker room, grabs his battered Patriots lunch box and heads to the cafeteria.

“I have 20 minutes to eat. And then I have to get ready for practice.”

His assessment of this year’s team? “Capable of playing better,” he says. “There have been times when they are not performing up to their level of ability. There are all kinds of successes. Winning is just one. In my time here, I have enjoyed periods of great success. In 1991 and 1992, we won back-to-back super bowl championships. But it is not just about wins. It is about preparing young athletes for life. We are here to develop the entire person.”

He pauses. “I heard this great quote on ESPN. ‘Hard work beats talent when talent does not work hard.’ And there is no substitute for hard work. With anybody. I think this year’s team needs to work harder.”

Preparation for today’s practice includes creating a plan that will install a new offense and getting the team ready for Friday’s homecoming game against Brighton. Six weeks into the season, with nearly 40 years of coaching under his belt, Coach Herman knows what to do.

As a kid growing up in Georgia, he was a three-sport athlete, playing football, soccer and baseball at Benedictine Military High School. He enrolled in Armstrong State College (now Armstrong Atlantic University) on a baseball scholarship.

“I am way too small for football,” he says.

He may have been too small to play in college, but he was asked to be a Pop Warner football coach when he was 18 and has not stopped coaching since. Over the years he has also coached both boys and girls tennis, track and field, baseball, softball, soccer, and football, and taught physical education, earth science, geography and even math classes at the high school. But he feels his biggest contributions are establishing a weight room at the school and creating a football booster club to help finance the team’s expenses.

“You cannot have any serious athletic program for any sport without a weight room and weight training,” he says. “Even golfers use weights these days. Before we had a proper weight room, we had a Sears & Roebuck bench and a cheap lat pull machine.”

Today, there is a large room filled with $15,000 worth of weights and machines.

“It is not state of the art, but it works,” Coach Herman says.

What is state of the art are the pads and helmets his team uses. “The same kind that colleges and professionals use. I do not skimp there.”

This was all made possible by Coach Herman’s second contribution: The Martha’s Vineyard Football Booster Club, which raises between $60,000 and $70,000 annually. The school budget gives the team $4,500 for equipment and uniforms.

“Obviously, that is not nearly enough — especially when we had 80 players. Or even 40 now. The booster club not only paid for the weight room, but also installed the lights on the field, provided AEDs, the Touchdown Football Club booth, bleachers, a press box, and pays for uniforms, equipment, jackets, awards, food, hotel rooms and gives out five $1,000 scholarships a year. They also sponsor the homecoming dance, which is the only other school dance other than the prom,” he says. “It has been an amazing program headed by Jack Law. But we will see what happens next year. He and executive secretary Denise Lambos, who has been with us since 1994, are leaving.”

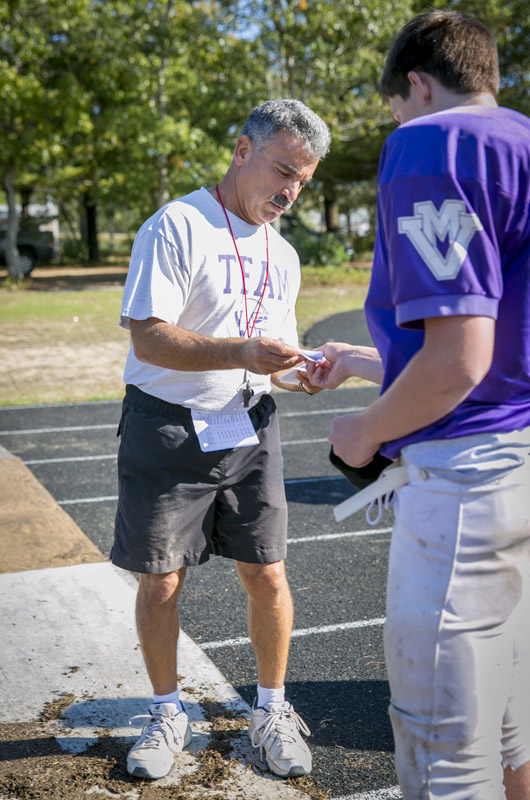

At five minutes after two o’clock, school is dismissed. Coach Herman changes from his physical education outfit into his coach outfit — black shorts and an MV football T-shirt that says, “TEAM” in big letters and “me” in small letters.

“The team is larger than the player,” he says. “They wear these T-shirts the day before the game.”

The T-shirts are just one of a seemingly endless stream of motivators for his players. He has an Iron Man award for any player who does not miss a single practice or game; he grades each player after each game (there were a lot of low grades after last Saturday’s game); they get a purple stripe award for game and practice performance (they can also lose them); he gives out awards for best offensive and defensive player, special teams, and a coach’s award of the week (Edgartown Pizza and Isola donate gift certificates for a free pizza for these awards).

“But,” he cautions, “There are some weeks when there is not a player of the week. They have to earn it.”

There are also rules if you play for Coach Herman. No beards. For safety. No earrings. Hair cannot be hanging out of your helmet. You must have a 70 grade point average or above. And there is zero tolerance for alcohol and drugs.

“I wish I could drug test my entire team,” he says.

Every two to three weeks each team member gets a progress report from the coach. As a result, he says, “More of my players are on the honor roll in season than off season.”

Practice begins with a warm-up, followed by circuit training, conditioning and agility drills. Half the team does the circuit training, which looks like an outdoor version of CrossFit. The other half runs through specific plays. Then the whole team moves through an obstacle course for agility, which demands speed, footwork and fearlessly charging through contraptions that simulate running through a pack of bodies.

Eight assistant coaches — Jason Dyer, Jason O’Donnell, David Araujo, Chris Scarsella, Tom Keller, Phil Hughes, DJ Kaeka and Jason Neago — help lead the 40 players through the practice. Dyer, O’Donnell, Araujo and Kaeka all played for the high school. Dyer has come back to help because it is Coach Herman’s last year. Some of the assistants are volunteers and some are paid. Though as assistant head coach, Jason O’Donnell says, “We make about 15 cents an hour.”

Coach Herman corrects him. “They actually lose money coaching. They do this out of love.”

Next, the players are run through a series of special teams plays. Coach Herman is not happy with what he sees.

“You get better or worse,” he yells to the team. “You never stay the same. Is your effort going to change you or sustain you?”

He bemoans what he calls the “Wussification of America.”

“Technology is the death of us,” he says. “We want everything quick, fast. Kids are enabled now. What about working for things? Learning how to cope? And, I’m sorry, but all of these parents who don’t want their kids to get hurt. I want to say, ‘Then don’t let them drive or ride a bike either. Don’t let them leave your house.’”

He shakes his head. “Besides, both my sons had injuries and surgeries from soccer. Not football.”

Coach Herman may be proud of his football program, but he is even more proud of his three children. Son Eric, 28, teaches Spanish at the Edgartown School. Son Adam, 26, works as the director of the clinical engineering department for a hospital in Baton Rouge, La. Daughter Gail, 23, is at the University of Massachusetts Amherst earning a graduate degree in speech and language pathology.

“They all went to this high school,” he says. “They got involved. Played sports. And all finished in the top six of their class. In that way, they take after their mother.”

His wife, Pam, teaches fourth grade at the Tisbury School. They met when Pam was working as an elementary school in Savannah.

“My sister in law offered to set us up. She showed Pam a picture of me and Pam declined. But she changed her mind and came to a football game that I was coaching. That was in October. Three months later I asked her to marry me. We’ve been married 31 years. The funny thing is that Pam doesn’t really like football.”

The mention of football interrupts the memory and he yells to the team. “Gassers! Let’s go! Now!”

Immediately, the players line up on the sides of the field and begin sprinting back and forth across the field as fast as they possibly can. This goes on for seven or eight minutes — until all the players are gasping for air. A few players stop running mid field. Teammates rush onto the field to help them. They know if they don’t put in a good effort, they’ll have to do more.

“Football is the ultimate team sport,” Coach Herman says. “It is like conducting an orchestra or playing a game of chess. You have to anticipate not just for the current play but for the plays that you think are going to be used next. You’ve got to get 11 bodies communicating, working together as one organism. If one person doesn’t do their job, the chances of being successful are greatly diminished. Everyone is important.”

As the sun begins to set Coach Herman keeps pushing his players to move through plays, up and down the field. The players begin to tire, but he is not giving up on his vision of molding them to be their best. But now, as he pushes and tweaks plays, his voice does occasionally get softer. He even praises a few kids.

“I want my players to know I care,” he says. “It is important. I tell my coaches that we should never hesitate to tell our players that we love them. They need our care. And they need to know it’s okay to show the fact that they care about each other.”

Practice winds down and the players put away the gear, except for two kids who run the field and do push ups to make up for disciplinary offenses. Coach Herman grows reflective.

“At the last practice of the season, I have all the seniors line up on the goal line and then every player and coach walks down the line, shakes their hand, thanks them, gives them words of encouragement and tells each senior whatever they want to say. It can be very emotional. Teenage boys crying. It’s not something you usually see. I also write a letter to the team and give it to a senior to read to the team. No one else gets to see or read that letter. It is personal. Of course I always thank everybody, but every year the letter is different. This year, being my last year, is going be difficult.”

His voice catches.

“And very special.”

This Friday’s game against Brighton begins at 6:30 p.m. at the regional high school field. There will also be a halftime ceremony honoring Coach Herman where all Vineyard football alumni, their parents, cheerleaders, touchdown club members and managers and assistant coaches of the Herman era will take the field to honor his career and legacy.

The Playbook on Donald Herman

Age: 57

Born: Savannah, Georgia.

Moved to Martha’s Vineyard: 1988.

Profession: head football coach at the Martha’s Vineyard Regional High School, physical education teacher, head softball coach.

Family: wife, Pamela; sons Eric and Adam, and daughter Gail.

Pets: Mowgli, “A mix of a black lab, plot hound and pain in the ass. But I love him.”

Workouts: In season, three days a week of weight training. Out of season, two to three days a week of cardio, in addition to the weight training.

Summer job: Edgartown park department doing beach patrol for South Beach. “We keep the beach clean and support the lifeguards.”

Only food he really hates: Liver.

Fandom: He has been a Red Sox fan since he was a kid. He used to be a Dallas Cowboys fan: “They were America’s team!” He is now a diehard Patriots fan.

Comments (15)

Comments

Comment policy »