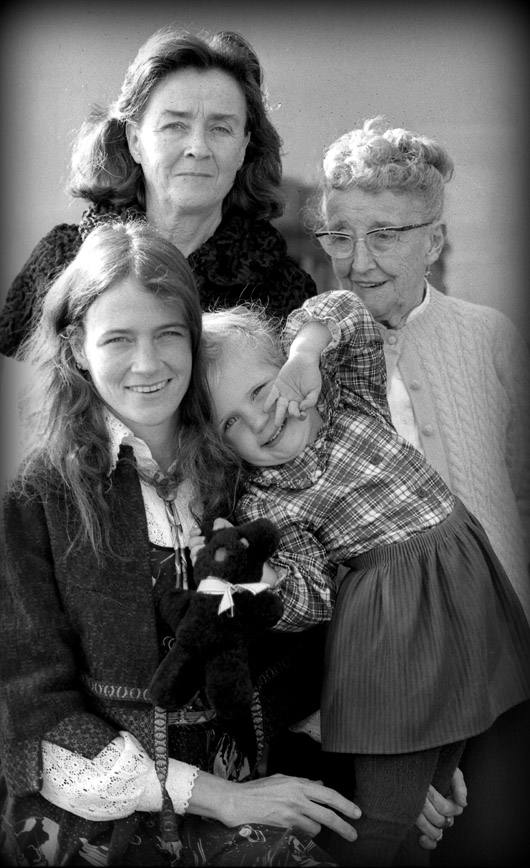

Trudy Taylor, the widely-admired matriarch of the musical Taylor family, died Saturday at her home overlooking Stonewall Beach in Chilmark, surrounded by family and friends. She was one month shy of her 93rd birthday. The cause was complications of old age, her daughter Kate Taylor said.

“The clock didn’t owe her much,” her son Hugh Taylor said. “She lived a long and wonderful life. She had a marvelous passing.”

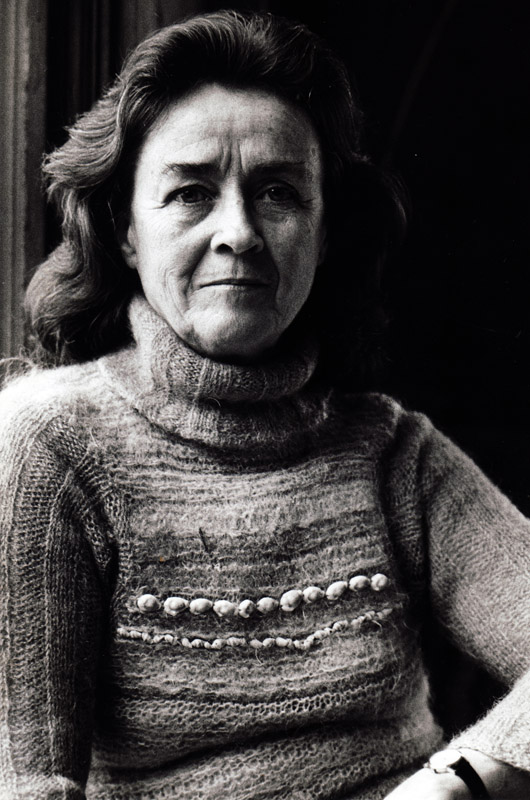

At once petite and sturdy, elegant and outspoken, Trudy had endless curiosity in people and the world around her, a trait she passed on to her children they all agreed.

“She had the uncanny ability to trust us and to let us go out and paddle off at six years old in a kayak,” Hugh said. “We just don’t do that anymore. She was instrumental in teaching us self reliance.”

His brother James Taylor echoed this sentiment in an interview with the Gazette in 2002 on the occasion of his mother’s 80th birthday party.

”Trudy’s life, her spirit and energy, is that of two people,” he said. He went on to explain how his mother did not impose control or judgment over her loved ones. “I think mothers like their kids to be settled and happy and safe. But Trudy has the ability to feel otherwise,” James said.

Gertrude Woodward Taylor was born on Nov. 7, 1922 and raised in Newburyport.

“My people were all fishermen, real fishermen,” she told the Gazette in an interview last year. “We’re Vikings, on my father’s side.”

Trudy attended Newburyport High school until the day she walked into the principal’s office and said she wasn’t coming anymore, because it didn’t fit her particular fancy. Even at a young age she knew what she wanted and spoke her mind.

In Boston she attended the Miss Child’s School and studied voice at the New England Conservatory. While there, she met her future husband Isaac Taylor, a student at Harvard Medical School. The two were married and raised five children together, born in quick succession between 1947 and 1953: Alex, James, Livingston, Kate and Hugh.

After medical school the Taylors moved to Chapel Hill, N.C. where Dr. Taylor taught medicine and eventually became dean of the UNC Medical School in 1964.

But it was hard to take the New England out of Trudy. To escape the heat of the south in the summer, the family began traveling north during those months, eventually discovering Martha’s Vineyard through friends from Massachusetts General Hospital who ran Tashmoo Farm.

“To placate my mother’s homesickness for New England we would come up every summer,” Hugh said. “She would load us in the station wagon, all five of us. Me and the dog in the way back, Alex up front, James, Liv and Kate in the middle seat. She led the whole brood through the summer.” The Taylors rented homes for a few summers beginning in 1949, with Trudy managing the family largely by herself, especially during the two years Dr. Taylor spent in Antarctica as a medical officer on a U.S. Navy operation called Deep Freeze. In May of 1952, prior to the first summer of her husband being away, Trudy wrote to Henry Beetle Hough, editor and publisher of the Gazette, seeking his help on a communication matter.

“I’m writing to ask if you know of a ham radio operator on the Vineyard whom I could learn about (I want his code numbers, etc.) so that the radio men in the Antarctic could contact him — thereby making it possible for my husband and me to communicate while I’m on the Vineyard,” she said in the hand-written letter preserved in the Gazette archives. “We’re going to be on the lovely/lonely end of your Island — way out near Lobsterville — in a cottage looking back at Woods Hole. The address is Gay Head.”

In September 1956, Trudy again wrote to Mr. Hough, this time to tell him about the summer that had just passed and how much the family had enjoyed their time on the Vineyard.

“Our August stay on Quitsa Pond and the edge of the sea was perfect,” she wrote. “How reassuring and marvelous it was to awake at night and hear the sea pounding away (knowing it’s for always and forever is the truly reassuring part).”

A few years later the Taylors purchased a cottage overlooking Stonewall Pond.

“The land wasn’t worth anything then,” Trudy told Linsey Lee of the Martha’s Vineyard Museum in an oral history done in 2012. “You could just buy land by calling the owner in Maine somewhere and he’d say “I’m dying to get rid of it. It’s not worth anything.’”

She became a year-round resident of the Vineyard in 1970. She and her husband divorced in the early 1970s. Dr. Taylor died in 1996.

On the Vineyard, Trudy was known for her large and sprawling parties that included a wide circle of family and friends. The New York Times wrote an article in 1968 about her bouillabaisse, including her recipe and praising her proficiency at gathering much of the ingredients herself.

“I was raised on a small salt marsh island at the mouth of the Merrimac River in Newburyport. That’s why I’m such a good clam digger,” Trudy said.

She was a master gardener too. In 1993, the Massachusetts Horticultural Society honored her with a Gold Medal. “This is a year-round garden, enticing one to prowl through beds of a seemingly infinite variety of perennials,” the citation said in part.

Lynne Irons, who writes the weekly garden column for the Gazette, was a good friend. “We traded seeds and advice,” Ms. Irons said. “And canaries too.”

Ms. Irons raised canaries in a large cage in her house, while Trudy let them “fly free in a big greenhouse attached to her house,” the columnist and veteran gardener recalled.

They spent many afternoons visiting with each other in their gardens.

“One time she came to my house and all the peonies were in bloom,” Ms. Irons said. “She grabbed her chest and said, ‘Oh, once the peonies go by, the honeymoon is over.’”

When not on the Vineyard, Trudy traveled the world, trekking the Himalayas, touring Ireland, sailing to the Galapagos Islands, visiting China six times — the first trip taken in the mid-1970s as part of the first wave of foreign visitors.

In August of 1975 she gave a talk at the Old Sculpin Gallery about her journey to Nepal that was covered by the Gazette.

“People get a little squirmy these hot nights, and Mrs. Taylor’s talk was perfect, not too long, not too stuffy and excellently planned,” the newspaper reported.

In an essay by Stan Hart published in the Gazette in March of 1979, he wrote about needing a long walk to clear his soul and deciding that Trudy would make a perfect companion due to her experience in the Himalayas. The walk went differently than expected.

“For one thing, Trudy has to stop at every inverted clam shell and study its contents and says things like, ‘You can see the whole ocean in microcosm within this shell.’ And so we would pause to examine it, peering at the dull water held in its concave basin, looking at the almost microscopic organisms inert therein while she considered the meaning of life, and I, noticing the shape of the object, thought of an ashtray.”

Mostly her time on the Vineyard was spent with her family.

“She loved being with the family and was a very supportive grandmother and they were devoted to her,” Kate Taylor said. “She truly was the matriarch.”

She nurtured her children’s creativity, giving them space to run and a foundation from which to grow.

“She was ferociously curious, and she taught us how to be project oriented,” her son Livingston said. “What we all do, we learned this from Trudy, to take on a task and get it done. I remember Hugh saying I’m going to open up an inn and eight months later there it is.”

Four of her five children turned to music and performing. On raising five children born in six years, Trudy told the Gazette in an interview in 2000:

“It was like running a little school. I raised them as a group. A very special group of people. Each different. All funny, smart, and very musical. They had space. They had privilege. I did not just leave it up to the school to educate my children.”

In an interview with the Gazette in 2002 she spoke movingly about her son Alex, who died in 1993 at age 47: “Sometimes it seems like 50 years, sometimes like 15 minutes. There’s no recognizing time in it. We all kind of wear him in a way.”

Trudy Taylor lived a Vineyard life of total immersion, her son Hugh said. She was a singer, painter, gardener, cook and creative knitter who designed clothes that were fashioned from materials that she collected on her travels. She loved the sea and sailing and in recent years held court every Sunday at breakfasts around the Island, in particular at State Road Restaurant in West Tisbury. She was an inspiration to her family and many friends for her boundless energy, her frankness and her belief that anything was possible, a trait she practiced as well as preached. Her philosophy about life could well be summed up best by herself:

“And sometimes in the morning if you can wake up and just see yourself in the mirror and get a good laugh, it’s good,” she said. “Life is too serious to be taken seriously.”

She was predeceased by her ex-husband Dr. Isaac Taylor and her eldest son Alex Taylor. She is survived by her sons James, Livingston and Hugh Taylor and her daughter Kate Taylor; her grandchildren James R. Taylor, Sally Taylor, Ben Taylor, Henry Taylor, Rufus Taylor, Elizabeth Witham, Aretha Brown, Alexandra Taylor and Isaac Taylor; and her great-grandchildren Claudia Taylor, Paige Taylor, Bodhi Bragonier, Fiona May Brown, Zuri Elizabeth Brown, Olive MacPhail, Violet MacPhail, Emmett Taylor and Tillie Taylor.

A gathering to celebrate her life will be held on Wednesday, Oct. 28, from 4 to 6 p.m. at the Chilmark Community Center. In lieu of flowers the family asks that donations go to Planned Parenthood.

Comments (7)

Comments

Comment policy »