With fall coming to an end, many winter moths have laid their eggs, but the males can still be seen fluttering around headlights and street lamps across the Island. Given their abundance this year, many anticipate another wave of defoliation next spring as the larvae hatch and begin feeding.

The winter moth, Operophtera brumata, only recently invaded the area, arriving on the Vineyard with a series of outbreaks beginning in 2005. Those outbreaks were much worse than in the past few years, but pockets of the Island have been hit hard by the larvae, which feed mostly on black oak, but also maple, birch, cherry and other trees.

Scientists are still trying to get a handle on the abundance and distribution of the species, as well as the scope of the problem. A lack of monitoring and research has left many questions unanswered.

For homeowners, management techniques can include using an oil spray in the winter or spring to kill the eggs before they hatch, or other substances that target the caterpillars.

Tim Boland, executive director of the Polly Hill Arboretum in West Tisbury, noted heavy feeding in Vineyard Haven and Oak Bluffs last year, with Edgartown starting to show higher numbers as well. “There has certainly been a distinct pattern of having Vineyard Haven as really the number one spot, Oak Bluffs second, and then Edgartown kind of a distant third,” Mr Boland said. But there is plenty of speculation as to why that is the case. One obstacle in gauging the problem is that winter moths closely resemble fall cankerworms, which have a similar impact on trees but breed earlier in the season. Mr. Boland said most of the moths he has seen around West Tisbury this year have been fall cankerworms. Other reports vary widely.

“You can ask 10 people who live in 10 different areas of the Island and they will give you a different answer,” said Suzan Bellincampi, director of Felix Neck Wildlife Sanctuary in Edgartown. “I’m seeing much more of them in West Tisbury than I’m seeing in Edgartown, and that’s been typical.”

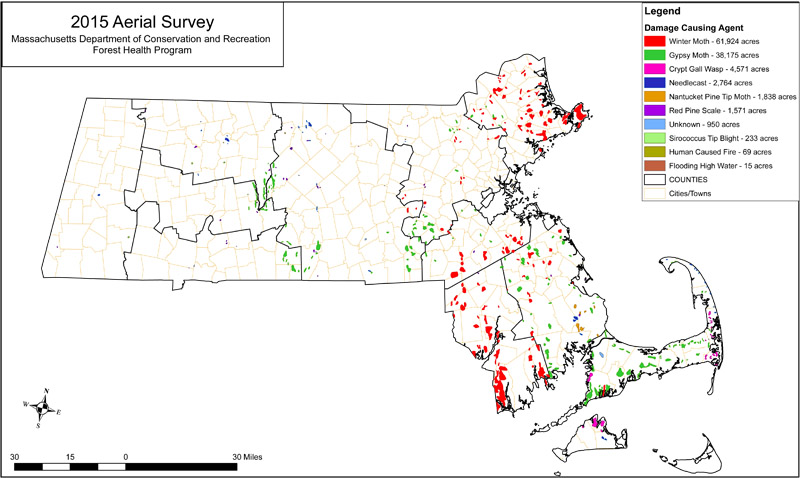

An aerial survey conducted this year by the state Department of Conservation and Recreation showed 61,924 acres of winter moth defoliation in the eastern part of the state, up from 36,468 acres last year.

But DCR forest health program director Ken Gooch told the Gazette this week that most of the damage on the Vineyard has been caused by gall wasps and gypsy moths. The 2015 survey shows two large areas of gall wasp defoliation, in Oak Bluffs and Tisbury, but no areas affected by winter moths.

The annual flyovers are typically followed by ground surveys to confirm the cause of defoliation.

“Winter moth chewing looks like the leaves were skeletonized, where gypsy moths eat everything,” Mr. Gooch explained. “Most of what we mapped was all gall wasp.”

Regardless of the cause, the overall damage to black oaks on the Island has been severe. “I was amazed at how many dead oak trees you have on the Island,” Mr. Gooch said. “Thousands and thousands of dead oak trees.” Most of the damage was in Edgartown and Oak Bluffs, he added, where there are more oak trees in general.

Jon Fragosa, owner of Fragosa Landscaping in West Tisbury, said the distribution of trees on the Island might correspond to the distribution of winter moths. He pointed out that maple trees here are limited to residential areas where they have been planted, rather than in forests, which might help explain the distribution

Another possibility is that winter moths are drawn to urban areas by the heat absorbed by pavement and buildings. Mr. Boland said down-Island towns are significantly warmer throughout the year as a result of development, and that trees there tend to flower earlier in the season.

“We see a very noticeable difference in terms of leaf-out in flowering of plants in Vineyard Haven compared to West Tisbury, and then all the way down to Aquinnah,” he said. “That range can be a week or more.”

Winter moths seem to prefer warmer temperatures in general, which may explain their coastal distribution, since coastal areas have warmer winters.

University of Massachusetts entomologist Joseph Elkinton, who has been studying winter moths since 2003, said the species has been observed as far west as Amherst. “But in these interior areas it’s not causing defoliation,” he said. “So it seems very likely that it has to do with winter temperatures.”

Mr. Elkinton doubted the effect of so-called urban heat zones on the Island, and suggested the difference might have to do more with predators in the soil. But he acknowledged that understanding the distribution patterns would require a major undertaking.

“We are trying to get a handle on some of the dynamics of winter moths . . . [and] understand what causes year-to-year variation in density,” he said. “But we haven’t really pulled our story together yet because it’s complicated.” Warmer temperatures in general are causing widespread ecological changes in the region. “Compared to 100 years ago, leaf-out is occurring about a week to 10 days ahead,” Mr. Boland said, referring to historical data and data collected by the arboretum over the last 15 years.

Ms. Bellincampi added that as seasonal patterns shift as a result of climate change, invasive species such as winter moths can often get a jump on their native competitors.

Last year’s mild fall may have contributed to the outbreak of caterpillars in the spring, Mr. Boland said, adding that the heavy snow and ice last winter may even have helped insulate the eggs.

Mr. Fragosa noted that this fall also was exceptionally warm. “So I would be surprised if we don’t have a pretty good out break of caterpillars next year,” he said.

Several management options are available on the Island, including prophylactic sprays and an organic bacterium that targets caterpillars and prevents them from feeding.

Sticky barriers around the base of trees may prevent the females from climbing up to lay their eggs (only the males can fly), but Ms. Bellincampi said that technique has not been fully studied. One sure way to help protect a tree, she said, is to water it well in the spring so that defoliation will not combine with draught and cause mortality.

The Island’s black oaks, in particular, have been under pressure from winter moths and other pests for several years. “You have had a lot of things going after the oak trees,” said Mr. Gooch. “They can only take so much.”

On the Cape, the introduction of Cyzenis albicans, a parasitic fly, has greatly reduced some winter moth populations. Mr. Elkinton and his research team have established the flies at 17 sites in the region, with many more in progress. He said the technique has not been applied on the Vineyard, mainly due to public opposition.

“You have a unique fauna of moths and butterflies out there that’s unique for reasons we don’t fully understand,” he said. “So people who are interested in this fauna might be leery about whether we should be releasing parasitic flies.” But he added that researchers are confident the flies only attack winter moths.

In Wellesley, he said, the flies cause about 30 per cent mortality, although the winter moth population has decreased by about 90 per cent. He suspected that the flies were lowering moth densities enough to allow a bigger opening for soil predators.

It’s likely that the problem is worse on the Cape, but Mr. Elkinton said that was still somewhat unclear. “The best data we might have would be defoliation surveys,” he said. “Other than that it’s just casual observations. It’s very difficult to tell.”

Comments (1)

Comments

Comment policy »