With tick-borne illness on the rise, federal and state health agencies are turning their attention to babesiosis, a lesser known but potentially life-threatening disease carried by deer ticks that is transmissible through blood transfusions.

The Rhode Island chapter of the American Red Cross, which handles most of the blood supply for Massachusetts, began screening its blood samples for babesia some time ago. It also has been sharing data from the program with the federal Food and Drug Administration, which is expected to require the screening of all blood samples in certain areas of the country.

Babesiosis and other tick-borne diseases, including Lyme, are endemic to New England, which spurred the Red Cross into piloting the screening program. The Rhode Island Blood Center, one of the few independent centers of its kind in the area, drew attention last year when it also began screening, laying off 37 workers in the process to cover the costs.

“Right now the focus is on babesia because that is causing multiple infections every year due to blood transfusion,” Dr. Catherine Brown, deputy epidemiologist at the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, told the Gazette this week.

Several hundred cases are reported annually in the state, with the numbers increasing dramatically. Between two and five of those cases each year result from transfusions, Dr. Brown said.

Nationwide, babesiosis is the number one infectious disease caused by transfusions, although other complications, such as abnormal reactions to blood, are more common.

The disease causes Lyme-like symptoms, with fatigue and aches, but usually not the characteristic bull’s-eye rash at the point of infection. Lyme, babesia and anaplasma are all carried by deer ticks. A small percentage of Lyme patients also contract babesiosis.

Usually, when a patient has indistinct symptoms, a physician will order tests for all tick-borne illnesses, including tularemia and Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Lyme tests are routinely performed on the Island, but in other cases, blood samples are sent to the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota for testing.

Last year the Martha’s Vineyard Hospital reported 25 cases of babesiosis on the Island, down from 36 the year before but up from 20 in 2013. Lab director Lynn Mercer told the Gazette that the figures were likely even higher, since Island visitors may not experience the symptoms until after they return home. Cases of both Lyme and babesiosis spike in the summer.

Vineyard Medical Center in Tisbury, which also tests for tick-borne illness, reports between six and 15 cases of babesiosis per year. Lab director Dr. Lena Prisco said the numbers tend to fluctuate from year to year, but have not increased dramatically.

She estimated that up to 600 samples in all, including those taken at the hospital, are sent off-Island for testing each year.

The illness is more prevalent on Nantucket than the Vineyard, but has been on the rise throughout the region. It also has a significant presence in the Midwest. Dr. Brown said a combination of factors, including increased habitat resulting from development, were to blame for the explosion of deer ticks in New England.

“The suburban areas that we have developed over the last several decades have created the perfect type of environment to increase populations of small rodents like chipmunks and mice — and deer,” Dr. Brown said. While rodents are the initial carriers of the diseases, deer provide food and a way for the ticks to get around.

On the Vineyard, discussions have occasionally turned to the resident deer population, which exceeds the density of most areas in the state — and whether culling the herd could help reduce the number of deer ticks on the Island.

Blood screening is another form of prevention, but would not directly affect cases of Lyme or other tick-borne illness, since only babesiosis is transmitted through blood transfusions. “That was the whole reason behind working on this babesia screening policy,” Dr. Brown said. “Babesia is the one that’s the risk.”

Dr. Prisco said she believed that a federal mandate would have little affect on the ability to give or receive blood on the Island. But the increased costs could potentially trickle down to the hospital.

“The discussion has been around the fact that anytime you add a screening process to the blood, it’s going to increase the cost of it,” Dr. Brown said. “The balance is that we need to protect public health, and yet the hospitals are also going to probably see an increased cost for that blood supply.”

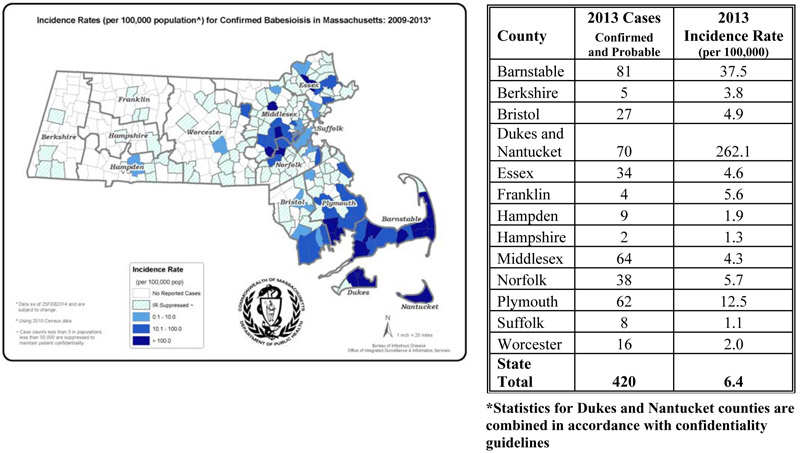

The state Department of Public Health reported 420 cases of babesiosis in 2013, an increase of 40 per cent from 2012. And for the first time in 2013, all counties in the state reported cases. The highest incidences were in Barnstable, Plymouth, Dukes and Nantucket counties. One out of three patients were hospitalized, and five cases were associated with recent blood transfusions.

Rhode Island reported 142 cases of the disease in 2013.

Comments (23)

Comments

Comment policy »