In the Oscar-nominated movie Spotlight, Boston Globe reporters take to the streets, go to court, pore through church directories and badger lawyers over the course of months to get to bottom of the Catholic Church’s systemic cover-up of child sexual abuse by scores of priests.

The film could be a tutorial for what people in the news business call shoe-leather reporting, that is, the act of journalists doing the painstaking legwork of tracking down and confirming all the facts before crafting them into a story for public consumption.

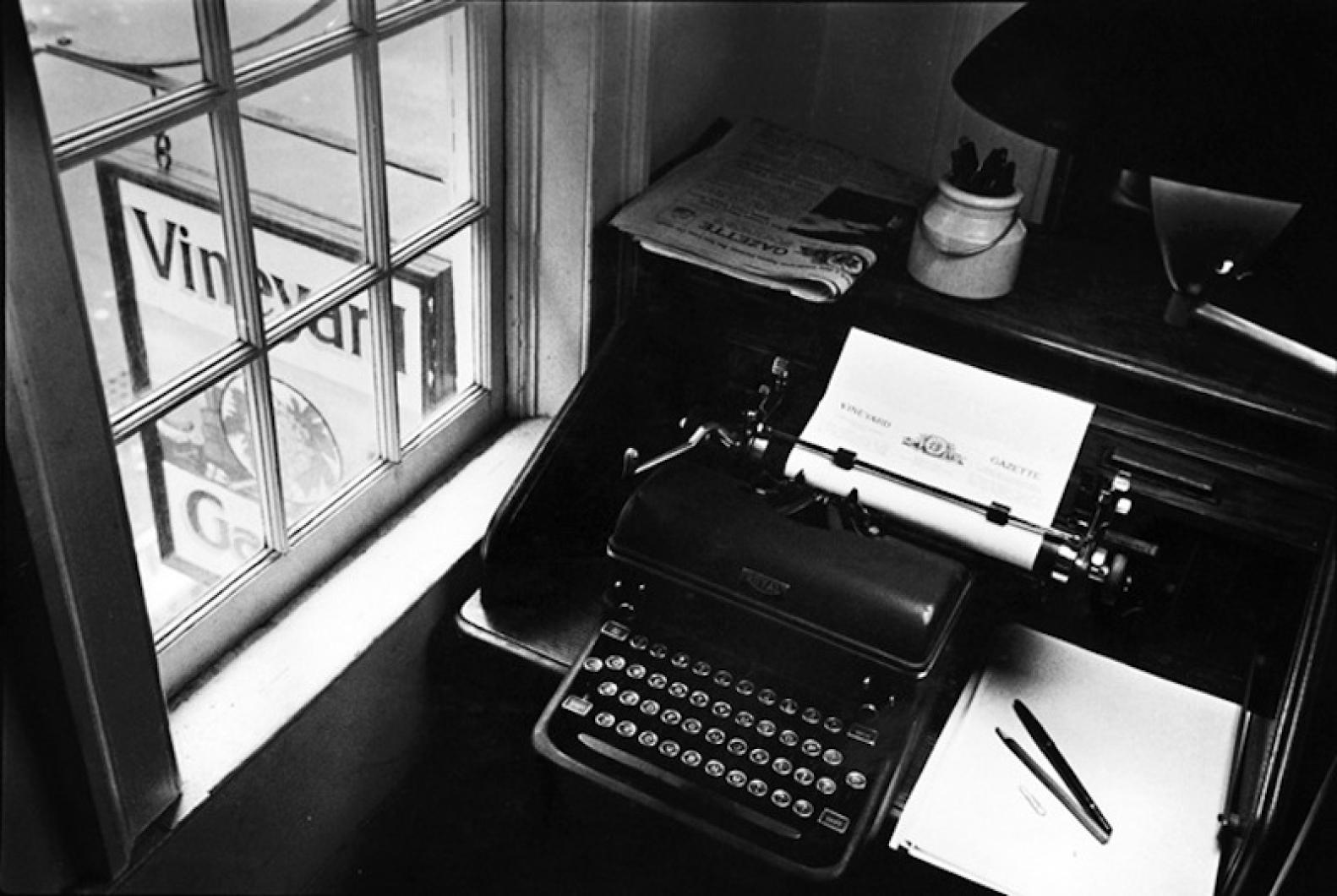

The surprising popularity of Spotlight, the movie, was one of the topics addressed by Walter V. (Robby) Robinson, the head of the Globe news team that won a Pulitzer Prize for its coverage of the church scandal, who spoke to a group gathered in the Gazette newsroom this week. The film’s underlying subject matter — the betrayal of trust by a powerful institution — was a big reason, he said. But people are also keenly interested in the process by which facts that are hidden — some by shame and some by design of those with an interest in shielding the truth — can be uncovered by careful, persistent reporting.

It’s no secret that in-depth journalism, let alone investigative reporting, is in decline nationally as editorial budgets continue to shrink. The traditional way newspaper newsrooms were funded — mostly by advertising, but also by subscriptions — has been disrupted, probably permanently, by the internet, and no reliable new business models have emerged.

Mr. Robinson, who was played with astonishing verisimilitude by Michael Keaton in the movie, noted that the number of full-time editorial employees at the Globe has declined from a high of more than five hundred and fifty in the 1990s to about three hundred and twenty five today. And that’s about twice the average for major metropolitan newspapers.

The shameful failure of the Catholic Church to confront and address pedophilia in the clergy as uncovered by the Boston Globe Spotlight team made for great drama. But the need for this kind of journalism continues long after the credits roll and the lights come up, in Boston, around the country and here on the Vineyard.

The Gazette is thankful to its advertisers and subscribers who enable us to provide the Island community with the quality journalism it deserves.

•

One irony of having the national spotlight turned on journalism in Massachusetts is that the state has among the weakest public records laws in the country. Last week, the Massachusetts Senate passed a version of a public records reform bill that has more teeth than the House version approved late last year. But of course the conference committee that will hash out the differences will conduct their deliberations behind closed doors.

The current law was last updated in any major way in 1973, long before the internet and well before personal computers were in common use. It would be two more years before Bill Gates founded Microsoft, three before Apple came into existence.

Many if not most public records are now created electronically, and the favorite dodge of officials who don’t want to release them — that reproducing them is too burdensome — is no longer credible. Still, the Massachusetts Municipal Association has been lobbying legislators heavily on that point.

The two legislators who represent the Vineyard, Sen. Dan Wolf and Rep. Timothy Madden, have been refreshingly supportive of a public records law that gives citizens and the journalists that represent them reasonable access to the workings of government. With fewer resources available to support investigative reporting, making it easier for the public to get at information its is entitled to see becomes even more critical.

Comments

Comment policy »