A sweeping new plan involving federal agencies, Native American tribes, six Northeast states and many other stakeholders may help set the course of ocean planning in the region for years to come.

Last week, the Northeast Regional Planning Body announced the completion of its Northeast Ocean Plan, which carries forward an executive order by President Obama in 2010 and is billed as a blueprint for ocean management in the region. It is among the first in a series of nine such plans across the country, as outlined in the executive order, although only three others are currently underway. A related plan for the Mid-Atlantic region was also announced last week.

The Northeast plan will direct nine federal agencies — the Environmental Protection Agency, the Department of the Interior and the departments of agriculture, commerce, defense, energy, homeland security and transportation — in their planning and review activities in the region. The various states, tribes and industry groups that helped develop the plan over the last four years will participate on a voluntary basis.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), which helped lead the project and provided much of the funding, said in a statement Monday that the plan “will promote more informed and coordinated ocean management among government agencies, transparency to the public, and predictability for industry.”

The plan comes against a backdrop of a nascent offshore wind industry in the region, with the first-in-the-nation Block Island Wind Farm coming online this week, and three projects now in planning in the waters off Massachusetts, Rhode Island and New York.

“It’s really important to have this plan in place so that we have a way to hold the federal community accountable for working together across our mandates and across state boundaries,” said Betsy Nicholson, regional director of the Office for Coastal Management at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and a co-leader of the regional planning body.

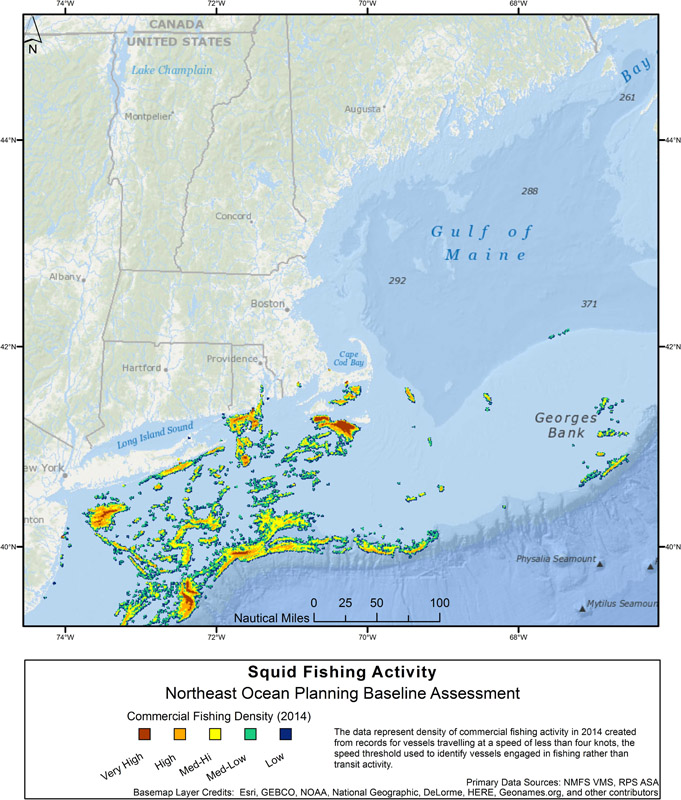

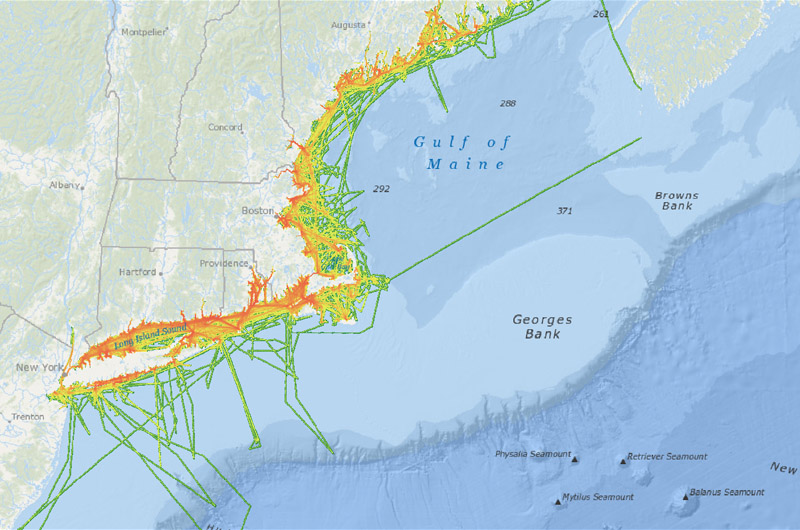

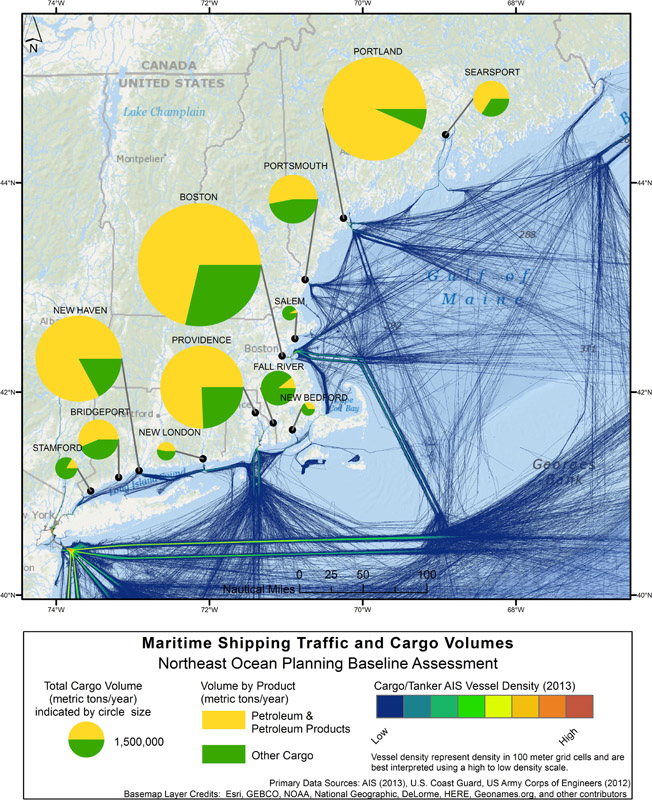

Among other things, the plan features thousands of new maps (available online at northeastoceandata.org) that will help federal and state agencies, along with developers, scientists and others, identify potential conflicts before a project gets started. Both the plan and the maps will be updated on a regular basis in light of a changing environment and regional economy.

Public meetings with stakeholders across the region set something of a new precedent, Ms. Nicholson said, with thousands of people weighing at workshops, forums and smaller meetings over the years, including several this years. “That kind of planning conversation didn’t exist,” she said, especially in regard to Native American tribes, which seldom have a seat at the table. The Wampanoag tribes of Mashpee and Aquinnah were heavily involved, she said, with four other tribes opting for an observational role.

Mark Alexander of the New England Fishery Management Council (NEFMC), who also has a seat on the planning body, welcomed the plan as laying out a new relationship between federal agencies and the fishing industry. “They are going to have to adhere to the best practices that appear in the plan,” he said of the agencies, “and hopefully that changes the whole nature of the way that the fishing industry can get involved.”

Jo-Ann Taylor, coastal planner for the Martha’s Vineyard Commission, who took part in two of the public meetings, noted the benefits of the Massachusetts ocean plan in terms of getting stakeholders to the table early on, and said she hopes the federal plan will have a similar effect. All navigable waters come under federal jurisdiction, so the plan will likely come into play on the Island, Ms. Taylor said.

Much of the plan focuses on offshore energy development, which has been leaning more heavily toward renewable energy in recent years. All but one state in the region has adopted renewable energy portfolio standards to increase renewable energy, and Massachusetts recently passed a groundbreaking energy bill requiring utility companies to purchase 1,600 megawatts of offshore wind energy in the next 10 years.

Deepwater Wind, which developed the Block Island Wind Farm and is working on another in the area, has welcomed the plan and online maps, but has also pressed for the planning body to follow through with continued updates and other commitments in the plan.

Representatives from Dong Energy and Vineyard Power, which are working on projects south of the Vineyard, did not respond to requests for comment this week.

The American Petroleum Institute, representing the oil and natural gas industry, was less welcoming of the plan, calling it “vague and incomplete,” and pressing for a clearer path forward for petroleum development in the region. As stated in the plan, New England does not currently produce its own offshore oil or natural gas, relying instead on distribution from other regions by pipeline, truck and shipping.

The plan generally anticipates a future based more on renewable energy such as wind and tidal power, and Ms. Nicholson noted the influence of climate change in driving the project forward. “It’s certainly an underlying theme,” she said. “And it’s why we have committed federal agencies to updating their data — because things change.”

Rip Cunningham, former chairman of the NEFMC, who had worked early on to get the council a seat at the table, said the plan was essential for stakeholders, especially in light of the rapid pace of offshore wind development in the region. “These big companies are going to do the development,” he said. “The rest of us who try to get in the way are going to be roadkill without the plan.”

Perhaps more than other resources at the moment, offshore wind illustrates the complexity of interactions among developers, marine species, fishermen and recreational boaters in the region. And while the Vineyard remains something of an outlier when it comes to commerce and fishing, it is also the closest land to the proposed wind farms in an area beginning about 14 miles south of Aquinnah. Those developments are well into the early stages of planning, with initial ocean-floor surveys completed this fall. But Mr. Cunningham said stakeholders will still have a chance to guide the process, since final plans have yet to be presented.

In terms of enforcement, the regional planning body has no regulatory authority on its own, although the nine federal agencies are required under the executive order to incorporate the plan into their regular activities.

The plan also outlines specific actions for each resource, focused on maintaining and improving data, informing existing authorities, and facilitating better coordination among agencies.

Meanwhile, Ms. Nicholson said various industries are already using the online data, and that previous experiences in Rhode Island and Massachusetts show that the data will likely play a significant role in offshore wind energy planning, which has included fierce opposition from some stakeholders in the region.

Looking ahead, the regional planning body expects to continue its outreach as the plan rolls out in the coming year. The next large forum may take place in the spring, and Ms. Nicholson expected updates to the online data on a monthly basis.

But she also indicated a somewhat uncertain future for the plan itself, given an incoming administration with its own priorities. Among other things, leadership of the regional planning body is set to shift from NOAA to the EPA, whose expected new director, Scott Pruitt, is a well known skeptic of climate change science. President-elect Donald J. Trump has himself shown skepticism over wind energy, and has attempted unsuccessfully to block a wind farm development near his golf course in Scotland.

“We don’t know what the new administration will do with the federal budget, but our mandates hopefully won’t change,” Ms. Nicholson said, adding that Mr. Obama’s executive order would continue unless rescinded by Mr. Trump.

“We are going to continue our good work, because it’s what the public wants,” she said. “And quite frankly, it’s us doing our jobs.” But in light of the uncertainty, and the high cost of public outreach in particular, she added: “We are going to have to get creative on all fronts going forward.”

Comments

Comment policy »