A northern long-eared bat on the Vineyard has tested positive for white-nose syndrome, a condition that has decimated bat populations on the mainland but until recently had remained undocumented in Dukes County.

The discovery suggests that Martha’s Vineyard is not the safe haven for the bats that researchers had suspected it was, and that the fungus Pseudgymnoascus destructans (Pd), which causes the syndrome, has gained a foothold here as well. The USGS National Wildlife Health Center in Madison, Wis., confirmed the presence of Pd in the bat earlier this month.

Antone Lima first observed the bat roosting under the trim board of a shed on his property in Oak Bluffs on an unusually warm day in February. He alerted BiodiversityWorks in Vineyard Haven, which has been studying northern long-eared bats on the Island since around 2014.

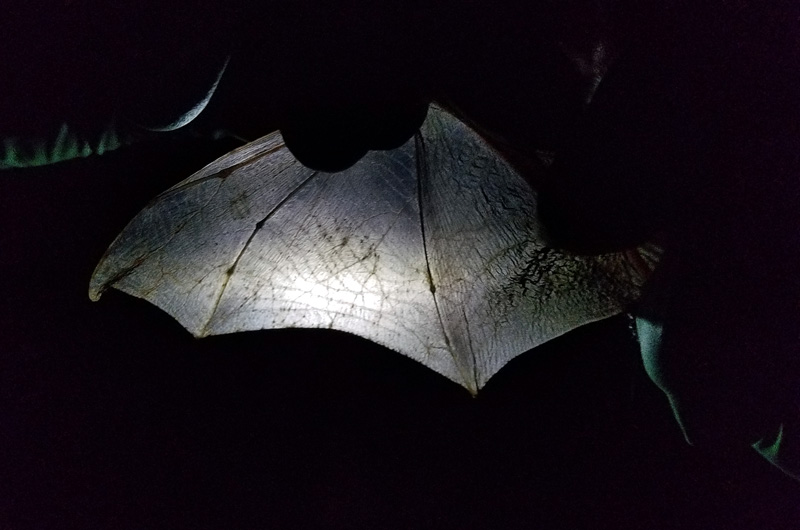

Following the usual procedure, BiodiversityWorks director Luanne Johnson and assistant director Liz Baldwin tagged the bat with a radio transmitter and let it go, hoping to discover where it was overwintering. Ms. Johnson said it was a healthy adult male, with only two questionable spots on its wings, as revealed by holding the wings up to a light.

Data from the radio transmitter shows that the bat did not leave the Island between when it was tagged and the next day, when temperatures dropped and the bat died. It also had not returned to its hibernation site.

“It wasn’t behaving as it should have,” Ms. Johnson said this week. “Bats can usually tell when the temperature is dropping and they usually find the shelter that they need, and this one didn’t.” The behavior was typical of white-nose syndrome, which rustles bats out of hibernation, causing them to burn critical energy and either starve or die of exposure.

White-nose syndrome was first documented in Albany in 2007, quickly spreading throughout the northeast, killing more than 90 per cent of its victims. Jonathan Reichard, assistant white-nose syndrome coordinator for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, said the syndrome range has been advancing about 100 miles per year.

“I was holding out some hope that maybe the Island was still clean,” he said this week, although he wasn’t surprised by the discovery. He noted that little brown bats have been documented flying between the Island and sites on the mainland that are heavily affected by white-nose syndrome. It’s likely that the Pd fungus arrived here on a bat from the mainland, he said.

While it’s possible the infected bat had arrived from off-Island just before it was captured, Mr. Reichard said a more likely scenario is that it encountered the fungus while hibernating somewhere on the Island. “It’s disappointing, but it’s not excessively surprising,” he said.

BiodiversityWorks has documented northern long-eared bat colonies in Edgartown, Vineyard Haven and Oak Bluffs, but has been unable to locate a hibernation site on the Island, making it impossible to know for sure whether the fungus has become established here. The thought was that the hibernation sites here may not be damp or cool enough for the fungus to thrive, but that has yet to be seen.

A female bat was tagged late last year, but didn’t go into hibernation before December when the battery died on the transmitter. But it also didn’t leave the Island, even when temperatures dropped below freezing. “She should have migrated by then if she was going to,” Ms. Johnson said. “So that was a really solid indicator to us that she was planning to spend the winter here.”

Coastal areas in general seem to offer some level of protection from white-nose syndrome, but researchers still aren’t sure why. Mr. Reichard said it could be anything from differences in temperature and humidity to the size of hibernation sites to the way northern long-eared bats interact with other species.

The Island lacks the caves, mines and tunnels where bats typically hibernate and may encounter the Pd fungus. Ms. Johnson has hypothesized that northern long-eared bats on the Vineyard hibernate in cellars or cisterns instead. She said it’s also possible that they hibernate in trees, where they often roost in the warmer months. To that end, BiodiversityWorks has begun monitoring tree cavities to determine their conditions in winter.

Researchers at the Nantucket Conservation Foundation discovered five northern long-eared bats hibernating in a crawlspace on Nantucket last November, after tagging a bat on Halloween and following it to the site. They returned in February and confirmed that at least one bat was still there. “That’s definitely a big deal for us, to confirm that they’re here year round,” said ecologist Danielle O’Dell, who is leading the project.

Nantucket has yet to confirm any cases of white-nose syndrome, but Ms. O’Dell said the recent case on the Vineyard has her on guard. She has already sent samples from the crawlspace to a lab at the University of New Hampshire for testing, and plans to sample bats she finds this summer.

Mr. Reichard said researchers were developing ways to target the fungus itself, with some tests already underway. He hoped to eventually be able to apply the methods on a larger scale, although that would still require knowing where the bats hibernate. He said people on the Island can help the bats by reducing other risks, such as predation by cats and the removal of dead trees where bats can roost.

Zara Dowling, a graduate student at the University of Massachusetts, has been using radio telemetry and other methods to study the relationship between bats and offshore wind turbines. Working with BiodiversityWorks, she helped set up three temporary radio towers on the Vineyard and one on Naushon last year to see if tagged bats are flying out over the ocean.

Ms. Dowling found that none of the five northern long-eared bats that were tagged last year had left the Island, although she noted that it was a small sample size. At least two little brown bats were documented leaving the Island.

BiodiversityWorks will continue its research this year, although it’s unclear whether the radio towers will return, since three of them were funded by a one-year grant from the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management. Ms. Johnson mentioned the possibility of eventually collaborating on genetic studies to see how bats on the Vineyard and possibly Nantucket differ from those on the mainland.

Mr. Reichard highlighted the importance of BiodiversityWorks’ research, given the many unknowns surrounding northern long-eared bats and coastal environments. “Their work out there is incredibly valuable,” he said.

Comments (3)

Comments

Comment policy »