Anyone now living who can remember the great whaleboat races that were held off Oak Bluffs and at New Bedford during the eighteen seventies must have been a small child and must be an elderly person today. The participants have gone; the whaleboats have disappeared from these waters and, except for modern reproductions which are not exactly true to the old models, from all the waters of the earth; and the eyewitnesses of the races are a dwindling few.

The whaleboat races, in fact, have slipped astern into history. They were sporting events of the first order, requiring skill, endurance, and keen judgment, and using one of the most beautiful of all the craft man has devised for the sea. To speak of the speed of the whaleboat, which was impressive, is not enough unless it is understood that this speed was functional in a boat built for seaworthiness and stout work.

“Most Perfect Water Craft”

Clifford W. Ashley, who wrote authoritatively upon the gear and craft of whaling. said that the Yankee whaleboat was “the most perfect water craft that was ever floated.”

In his description he went on: “A whaleboat had no deadwood aft, as this would interfere with quick turning. There was a very pronounced sheer and the ‘run’ (after-body) was considerably finer than the ‘entrance’ (forward end). An average boat was about twenty-six inches deep amidships and rose to thirty-four to forty inches at the ends, the stem being slightly higher. The typical whaleboat was always ‘single-banked’ - that is to say, there was but one oarsman to each thwart, and the men were staggered, which means the oarsman sat the full width of the boat away from his rowlock, instead of in the middle of the boat. This staggering of the men was necessary in order to balance the great length of the oars, which were the longest used in any service.”

Inevitably, the question arose of just how fast a whaleboat could be made to go through the water when handled by a noteworthy crew; and this was the question that led to the races. It was demonstrated in due course by the champion Martha’s Vineyard crew that their whaleboat could do two miles in 17 minutes and 18 seconds.

Could any other whaleboat do as well? That point may remain in some doubt, because the Vineyard crew used a whaleboat built by Uriah Morse of Edgartown which, in one respect, departed from the classic type. Uriah Morse had built many of these craft for whaleships to use in long and far voyages, but in this case he took on a special assignment. What was wanted was a whaleboat that would be fast, and not necessarily one that would ever be steered on a whale.

Oak Thwarts, Unsupported

Mr. Morse, therefore, made the thwarts of this boat out of oak, and he put no supports under them. In all other respects the boat was a standard model of the time; it was an unexceptional competitor. But the effect of the minor changes as to the thwarts or seats was this: when the oarsmen pulled on their long oars, some of the force was transmitted to the thwarts, which were pushed downward. As they gave in this manner, they tended to pull in the sides of the boat, making the craft momentarily more slender and sending it through the water with some slight extra thrust of speed.

The ancestor of the whaleboat has been identified as the Indian canoe, and Uriah Morse had contrived a way, a legitimate way, to make this racing boat a little more like a canoe than its contemporaries. This secret of construction was never fathomed at the time; rivals of the Vineyard crew fretted and argued, but they could never see that the Vineyard boat - except that it might have been a trifle lighter - was any different from the whaleboats they were using.

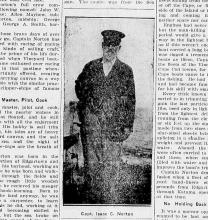

Anyone who wishes to see the famous whaleboat raced by Cap’n Ike Norto0n and his crew may do so at the Dukes County Historical Society in Edgartown, for the boat is carefully preserved and on exhibition there.

The first of the great races - and the adjective is used advisedly - was held in August, 1875. Oak Bluffs was nearing its nineteenth century peak as a popular summer resort; the previous summer President Grant had paid his famous visit, and had almost professed conversion at the camp meeting. The bathing beach, the steamboat dock, and the bluffs made excellent accommodations for the crowds to watch the races, not to mention the verandas of hotels and cottages.

For those who wanted to follow the races more closely, the steamers Frances, River Queen, and Verbena were on hand, and the spectator fleet of yachts included the cup yacht America, owned by Gen. Ben Butler; the sloop Maggie, owned by Gen. Tom Thumb; the Whitecap, owned by J. Malcolm Forbes; and the steam yacht Ydeal, owned by former Mayor W. F. Havemeyer of New York city.

In the racing, New Bedford was represented by whaleboats and crews bearing the names Marengo, Sixth Ward, Laetitia, Squid, Winder, and Currier. The Black Fiend was an entry from Fairhaven. Edgartown had chosen the name Last of All, probably with wry irony, and the crew comprised the following: captain, William Fisher; harpoon oar, George Fisher; bow oar, James Matchett; midship oar, Charles Coffin; tub oar, Allen Mayhew; stroke oar, W. J. Worth.

Prizes of $50, $25, $15 and $10 were offered, and the course measured two miles from the judge’s boat around a stake boat to the northeast, near the westerly end of Squash Meadow Shoal, and return.

A pistol shot sounded, and all the boats started except the Edgartown boat, the crew of which had become engaged in an argument. The cause of the dispute is not of record, but the altercation was cut short by Ike Norton, a young man raised on a farm, who got into the boat and replaced Charles Coffin at that deadly midship oar - eighteen feet long, and a regular killer.

The midship oar, the oarman sitting to starboard and rowing to port, had the help of two so-called short oars of sixteen feet, balanced by two oars measuring seventeen feet on the other side of the boat. (Usually the three oars were on the starboard side, but it was not so with Ike Norton’s boat.)

Late Start, But Then -

The Vineyard crew pulled out in the wake of New Bedford and Fairhaven whaleboats that had started well ahead; in a little while it passed the Squid, then shot past laetitia. Then the Vineyarders went by Black Fiend, Marengo, and Currier in turn, but only by hard pulling could they overtake Winder. After the turn around the stake boat an unfavorable wind and strong head tide made the going more difficult. At the finish line, Sixth Ward led with an elapsed time of 20 minutes, 30 seconds, and the Vineyard entry was second with 22 minutes, 30 seconds.

The last boat, Squid, took 25 minutes, 37 seconds for the course.

The judges had Sheriff William S. Cobb, a summer visitor, as chairman, and these whaling captains: James A. Crowell, William T, Hawes, James C. Stafford, Ariel Chase, and Ariel Norton. That evening a reception and collation were tendered to yachtsmen, captains and others, at the Sea View hotel, and the Vineyarders collected their prize money of $25.

The next Fourth of July - 1876 - four New Bedford crews raced their whaleboats at that city, to a considerable amount of enthusiasm and publicity. The Vineyard crew did not make the trip.

This account of the event appeared in the New Bedford Standard the following day:

Harbor Alive with Spectator Craft

“The harbor above the bridge was alive with all sorts of craft some time before the hour announced for the regatta, 3 o’clock. Among others were steamers Helen Augusta,Nellie, Favorite, and the little steamer Jennie. The guests of the city occupied the schooner Lottie Beard, with Martland’s Band on board. The judge’s boat at Fish Island was the yacht Flash, with Smith’s Band. he Azores Band was on George Howland’s wharf. In addition to the people who swarmed every kind of boat and vessel, thousands were clustered on wharves and buildings, the bridge and island.”

Sixth Ward was once again the winner, with time of 17 minutes, 22 seconds for a course that led a mile upstream, turning from west to east, and back to the starting line. In second place was the crew that called itself Centennial - because this was the year of the great Centennial Exposition at Philadelphia - with time of 18 minutes, 25 seconds. It was announced that these two crews would go to the exposition in September to race on the Schuylkill.

But the Vineyarders, although they had not been on the scene, were well aware of what happened, and they were not prepared to yield the championship to Sixth Ward. Interested heightened as arrangements were made for races at Oak Bluffs in August.

It may be as well to insert here the New Bedford account of the August races, as representing a judgment certainly not biased in favor of the Vineyard crew. The Vineyard Grove correspondent of the New Bedford Standard wrote as follows:

A Grand Gala Day

The first steamer arriving at our wharves brought nearly 300 people, and as each steamer arrived, the appearance of the landing and the several piazzas of the Sea View House was that of a grand gala day in our cities. About 12:30 the steamer Favorite from New Bedford landed a large party of excursionists, and with the small parties that arrived in sailing boats, our population for the day was much larger than for any previous day of the season.

“The three boats, Sixth Ward, Centennial, and Vesta, with their respective crews, were brought over by a fishing smack, and the boats as well as the crews arrived in excellent condition. The boat from Edgartown, after arriving at the Bluffs, was found to be in a leaky state, and considerable time was spent in calking it and otherwise rendering it ready for the race.

“The captain of each boat having already taken his position for starting, the several crews practiced for nearly half an hour, and at half past one the judges were anchored nearly opposite the Crocker cottage located at the south end of the plank walk. Calling the boats into line, the judges gave the signal for them to start and this part of the program was finally done.

With Stout Hearts

“The boats were in an exact line of position at the signal, and with stout hearts the men started for the prizes. The Sixth Ward, Capt. Charles G. Taber, took the lead at once, and while the Edgartown men were in good earnest to keep up, they lost their stroke and were nearly a length behind in a second. The Centennial started off with an excellent stroke, and by pulling steady sure kept very near the Sixth Ward for the entire course.

“As the boats rounded the stake boat, the two judges who were stationed at that point encouraged them heartily, and the order of their position was: Sixth Ward, Centennial, Vesta, Edgartown.

“On the home stretch the Edgartown gained on the Vesta and succeeded in passing it. As the boats passed the Lovers’ Rock near the bathing grounds, the Sixth Ward made extra exertions and won the race by eight seconds. The Centennial came in second, Edgartown third, and Vesta fourth.

“It was claimed by the Edgartown crew that they could have easily come in in better time had their boat proved tight and their gunwales sound. When half way around the course one of the gunwales broke, and the oarsman seated there labored at a disadvantage for the rest of the course.”

“A Lee-tle too Long Time”

So ends the New Bedford report, except that Hon. Abraham H. Howland Jr., one time mayor of that city, was among the guests at the Sea View that evening. When Sheriff Cobb presented the prize money, he came at last to the Vesta and said, “Captain, you and your crew are to be congratulated in holding out finely, and I will say that you took a good pull, a long pull, and pull together, but you took a lee-tle too long time.”

These were the first whaleboat races in which Ike Norton was joined by his brother Cyrus, known as “Cise.” Where the boys had got hold of their battered old whaleboat is not now remembered, but it proved to be beyond any last-minute help they could give it. They had shoved it into the water with the calking incomplete, and while it raced over the course it carried not only an estimated weight of 1,000 pounds of oarsmen, but also the greater part of four barrels of sea water. The boat had leaked like a sieve the whole distance.

The time was as follows: Sixth Ward, 21 minutes, 54 seconds; Centennial, 22 minutes, 2 seconds; Edgartown, 22 minutes, 5 seconds; Vesta, 22 minutes, 44 seconds.

The Gazette account of the race referred to the breaking of the gunwale and said that thereafter the corresponding oar in the Edgartown boat had to be handled “with tender care and affectionate solicitude.”

As Ike, Cyrus, and the other boys put away a good meal at Mrs. Robinson’s boarding house that night, this lady remarked, “I’d like to see you young fellows have the right kind of craft to race in.” One word led to another, and it was then that Ike Norton decided to have a talk with Uriah Morse, builder of whaleboats. Form here on in, the story was going to be different.

Won Exposition Races

Meantime the Sixth Ward, Centennial and Vesta crews and their boats went to the Philadelphia Exposition in September and raced on the Schuylkill in odd fresh-water grandeur. The Sixth Ward outfit wore white shirts and blue pantaloons, all the oarsmen wore white handkerchiefs about their heads, and the boat-headers had donned fancy turbans and body sashes. It turned out that New Bedford had no opposition, for the New London entry failed to show up, and a Philadelphia crew was disqualified for having no whaleboat.

There were 35,671 paid admissions at the Exposition that day, and great crowds lined the river. After one false start, the three crews got away in good shape, and voices were heard yelling, “Whale ahead!” and “There she blows!” Vesta won handily, with time of 25 minutes and 51 seconds for a distance that was not mentioned in the press dispatches. The winning crew got $100, the others nothing.

This was how things stood as the season of 1877, third summer of the whaleboat races, approached - except that the Vineyard crew was now provided with the new boat Ike Norton had contracted for with Uriah Morse. The crew consisted of: captain, Ike Norton; bow, Julius G. Lux; tub, William Pease; midship, Cise Norton; stroke, John W. Gordon; harpooner, George E. Smith.

A second Vineyard whaleboat was entered in this race, under the name Yankee. Its crew: captain, Eugene O. Thaxter; stroke, Manuel Thomas; tub, George Fisher; midship, Charles Fisher; bow, Joseph Matchett; harpooner, Thomas Wimpenney.

Judged from Schooner

The judges were stationed on the schooner Northern Light, anchored just off the foot of Canonicus avenue.

At the signal, off went Sixth Ward, taking a good lead, as expected by most of the spectators. But in about a quarter of a mile, Ike Norton’s boat drew even and for all of three minutes the two whaleboats fought it out, beam on beam; then Ike’s boat shot out front and kept the lead for the rest of the course - two miles and a half in a rough sea. The winning time was 24 minutes, 50 seconds. Sixth Ward had been unable to do better than 27 minutes, 55 seconds to take second place.

The margin of this victory was sensational. It is remembered that in some races Ike Norton and his boys coated their boat with black lead to give her a greasier movement through the water. Presumably that was done in this race.

A New Bedford correspondent noted that the steam launch Oklahoma followed the boats over the course and gave a salute of honor to the winner. And Holder M. Brownell, host of the Sea View House, extended the courtesies of his hotel to the several crews. Captain Grover of the Grover House was also liberal in his attentions to the crews. So everything had turned out nicely for the Vineyard, but not so nicely for the Sixth Ward and New Bedford in general.

Determined to Win

Now came the summer of 1878, with rivalry keener than ever, and the Sixth Ward determined to show that Ike Norton’s crew could be beaten. Several thousand people lined the bluffs commanding a view of the course that extended three miles - covering both ways - from the yacht Witch of the Wave, anchored off Cluster Village, to the stake boat off the Highland wharf. Allen Mayhew replaced William Pease at tub oar in the Norton boat.

Another Vineyard entry had for its crew Jason Luce, Edward Luce, James Matchett, Benjamin P. Hawes, F. D. Bailey, and Thomas E. Gardner.

The Sixth Ward crew should also have the names of its members a matter of record: captain, Eliphalet Haskins; harpooner, Curtis Jenkins; bow oar, Sylvanus Westgate; midship, Daniel Jennings; tub, G. B. Wilcox; stroke, William Westgate.

There was not much to write about the 1878 contest when it was over. Ike Norton’s boat made time of 27 minutes, 10 seconds, with Sixth Ward following in time of 29 minutes. Jason Luce’s crew required 31 minutes for the course.

It was now becoming clear that the Vineyard had a combination of championship caliber - the crew including Ike and Cise Norton, and the whaleboat built by Uriah Morse. This combination was heading way out beyond any effective competition.

The Conclusive Test

But the Fourth of July races at New Bedford in 1879 were to be the conclusive test. Ike Norton’s crew rowed their boat to the city, and tradition says they left the steamboat dock after the steamer, overtook her, and rowed ahead of her all the way, a distance of almost twenty-five miles. It must have helped some that they did not have to observe channel buoys.

Even in the Acushnet River the sea was rough on that memorable July Fourth, and here is the New Bedford Standard’s account of the races:

“The regatta on the river commenced promptly at 5 o’clock p.m., the advertised time. Heap’s American Band was stationed on Fish Island, and the Uion Cornet Band was stationed on the New Bedford shore, and these played alternately and with excellent effect during the entire progress of the race. Nearly every available space on the main and island was covered with spectators, while the water was alive with craft of all descriptions. The committee of arrangements secured schooner Samuel C. Hart, and this contained a large number of guests, being towed into the stream by steamer Nellie, while the judges with a large number of friends were on board Capt. William West’s yacht Theresa, anchored near Fish Island, a short distance to the south and west of its northerly point.

On an Imaginary Line

“The contesting boats started from an imaginary line drawn from the yacht to the north end of Wilcox and Richmond’s wharf. On the stakeboat near Dogfish Bar were William R. Sherman and George M. Crapo.

“Owing to the water being rough, the order of the races was changed somewhat from the advertised program, and first came the whaleboats, with entries by the Sixth Ward and Sixth Ward Jr., crews of this city, and Oak Bluffs, crew of Edgartown. When the time came for this race, the two New Bedford crews refused to row, wanting the prizes equaled to $30 and $20, instead of $40 and $10.

“The race was rowed by the Oak Bluffs boat alone, the crew of which consisted of Isaac C. Norton, captain; John W. Gordon, stroke; Allen Mayhew, tub; Cyrus B. Norton, midship; Julius G. Lux, bow; and George A. Smith, header. They pulled over the course of two miles in 17 minutes and 18 seconds, which is said to be the fastest time ever made in a similar race for the same distance in our harbor.

“The Oak Bluffs crew naturally felt very much pleased at their good record, and say that they pulled the race without any special training this year, their boat not having been launched until last Tuesday, and they had one green man. After pulling the course they offered to get up another race with either the Sixth Ward or Sixth Ward Jr. crews, for the second prize offered by the committee, or for a purse of $25, offering to exchange boats with their competing crew, but the committee had no authority to act in the matter.”

The Record Still Stands

And that was the end of the great whaleboat races, with the New Bedford crews refusing to race, even when they had a chance to show what they could do in the whaleboat Uriah Morse had built for Ike Norton and his boys. There are many traditions and stories about that Fourth of July, but this contemporary account would seem to be accurate. The time made by the Vineyard boat and crew still stands as a record, and the championship never passed to any competitor.

It is narrated, no doubt correctly, that when Ike’s crew rowed that day, the oarsmen ripped off their coats and shirts and tossed them into the bow - and three strokes later all these garments were in the stern.

And there is also the record of a triumphant and, all things considered, a magnificent gesture. Sometimes when they were rowing for practice, Ike Norton had cautioned Cyrus not to break his oar. But now, as the all-time record was established and history made, Ike called out: “Break your oar, Cise!”

And Cyrus snapped his midship oar apart in two places.

Comments