Cape Pogue resident Donald Greenstein has been finding lone star ticks on his property for years, but never in their current numbers. In June, after reading about the Island’s Tick-Borne Illness Reduction Initiative, he began reporting the encounters to Island biologist and tick expert Richard Johnson.

Mr. Johnson quickly surveyed a small portion of the property, collecting 30 lone star ticks, including 10 adults, covering a distance of about 1,000 feet along a path.

“It’s an order of magnitude different than anyplace else I’ve seen the lone stars,” Mr. Johnson said Wednesday evening after the Edgartown conservation commission had issued an emergency clear-cutting permit for a portion of Mr. Greenstein’s property.

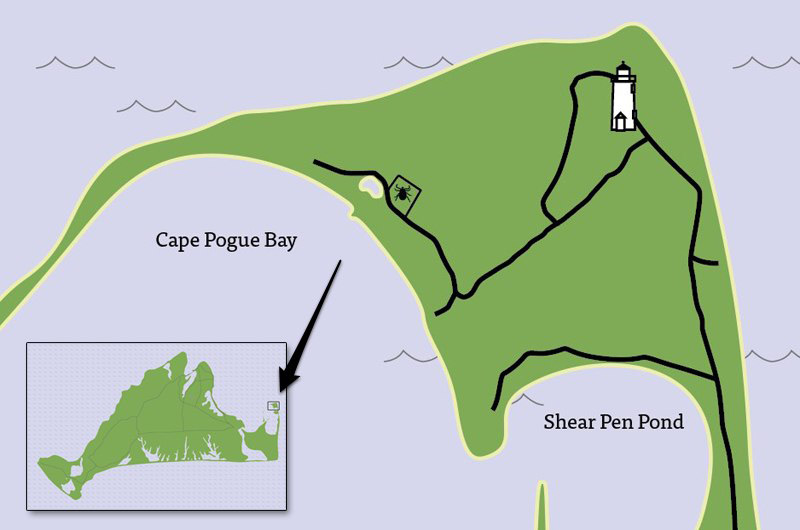

A one-acre test site on the property at the remote northern tip of Chappaquiddick will help determine the best ways to control the disease-carrying ticks, which now infest Long Island, Cuttyhunk and Nashawena island, but were thought to have a more modest presence on the Vineyard.

“You are going to hear more about these,” Mr. Johnson told the commission, which had gathered in the town hall in Edgartown on Wednesday evening. “They are a real problem.”

Mr. Greenstein suggested that the abundance of lone star ticks on his property was due to the heavy snowfall this winter, which may have had an insulating effect. Ticks thrive under damp conditions, and removing underbrush, woodpiles and other habitat can keep their numbers down.

In a letter outlining his intentions, Mr. Johnson said the abundance of lone star ticks on the property may indicate a much larger problem. With many acres of similar habitat surrounding the property, he wrote, “there could be tens of thousands of lone star ticks in this area.”

The species has been observed on the Vineyard as far back as 1985, but its establishment is unproven, since all three life stages — larvae, nymph and adult — have yet to be reported. Mr. Johnson said it was unclear whether they arrived here on birds or are in fact breeding. Over the next three months or so, he plans to comb the area for lone star tick larvae. A discovery would confirm that breeding is occurring.

Sam Telford, a renowned tick expert at Tufts University who cochairs the environmental arm of the Island tick initiative, said lone star tick populations have increased on the Vineyard. He cited “reliable sources” on Chappaquiddick who have found hundreds of small ticks in one spot, which may indicate the breeding of lone star ticks, which lay about 6,000 eggs at a time in small areas. “I believe it is very likely they are breeding there in certain sites,” Mr. Telford said Thursday. “What we need to do now, to the best of our ability, is to identify those sites and wipe them out.”

Large-scale management efforts might include brush cutting, animal grazing, controlled burns or a combination of all three, Mr. Johnson wrote, although each would have its drawbacks. “None of the options that I can see are ideal,” he said.

For the time being, Mr. Johnson plans to start small and learn by trial and error. It’s possible, he wrote, that clear-cutting could make the problem even worse, since the debris left over may provide more damp, shady habitat. He hoped for some initial results by the end of the month.

The adult females have a characteristic white dot on their backs, but the nymphs are harder to identify. In general, the species is rounder, flatter, lighter in color and faster moving than other ticks. Unlike other species, lone star ticks can distinguish between light and dark and will move toward you. And their bites are painful. “The good news is you are not going to get bit by an adult and not know it,” Mr. Johnson said.

Like other ticks, the species carries several diseases, including tularemia, which is potentially deadly, and STARI (Southern Tick Associated Rash Illness), which has symptoms similar to Lyme disease.

“You have to be so proactive with this,” said Mr. Greenstein. “I’m scared for my life out there. I’ve been out there for 28 years. Nothing has bothered me. The lone star tick is something in its own.”

Edgartown health agent Matt Poole said the apparent hot spot on Chappaquiddick was not an urgent public health hazard, “any more than any place where there are deer ticks or wood ticks.” But he added that it was “absolutely something that needs to be taken into account by people who are outside.”

The Edgartown board of health will continue working with the Tick-Borne Illness Reduction Initiative to establish a response to lone star ticks and as sist property owners taking preventive measures. Earlier this year, the initiative asked the public to report any encounters with lone star ticks.

The Martha’s Vineyard Boards of Health website includes resources related to tick-borne illnesses and prevention, including landscaping techniques. Public information related to lone star ticks is still being compiled, Mr. Poole said.

For property owners, Mr. Johnson recommended applying the chemical pyrethroid in its granular form, or spraying another chemical, permethrin, on a towel and swiping along the edges of the property repeatedly for five weeks. Ticks will latch onto the passing towel and be killed. “If you do this over and over, it will make an impact,” Mr. Telford said.

In southern states, considered the primary lone star tick habitat, controlled burns are one management strategy, but they must be repeated for several years. The remote location of houses on Chappaquiddick might make controlled burning a challenge here, Mr. Johnson wrote, but he felt it was “certainly worthy of consideration.”

Lone star ticks have moved north, he said, due largely to global warming. He noted that Fire Island in New York, which is now thoroughly infested, is similar to parts of Chappaquiddick, with cedar and bayberry growing in flat, sandy areas. The ticks on Mr. Greenstein’s property were especially dense along a new path through a cedar and bayberry thicket, he wrote.

Mr. Greenstein believed the management efforts on his property could benefit the entire Island. But he did not believe that clear-cutting alone would solve the problem.

“Personally I think we need a controlled burn besides the brush cutting,” he told the commission on Wednesday. “But that’s never going to happen out here.”

Commission chairman Edward Vincent Jr. recommended making the clear-cutting an ongoing project using whatever methods Mr. Johnson found to be within reason. “If it becomes something more, then he can come back to us and discuss what needs to be done,” Mr. Vincent said.

The meeting eventually gave way to several smaller discussions about how best to approach the problem. In the end the commission agreed to allow Mr. Johnson simply to act within reason.

In some ways Mr. Johnson is entering uncharted territory. In his letter, he reached out to longtime Chappaquiddick resident Edo Potter, along with Tom Chase of the Nature Conservancy, Chris Kennedy of the Trustees of Reservations and Mr. Telford for guidance. “There are people looking at it but there is no silver bullet,” he said.

Comments (13)

Comments

Comment policy »