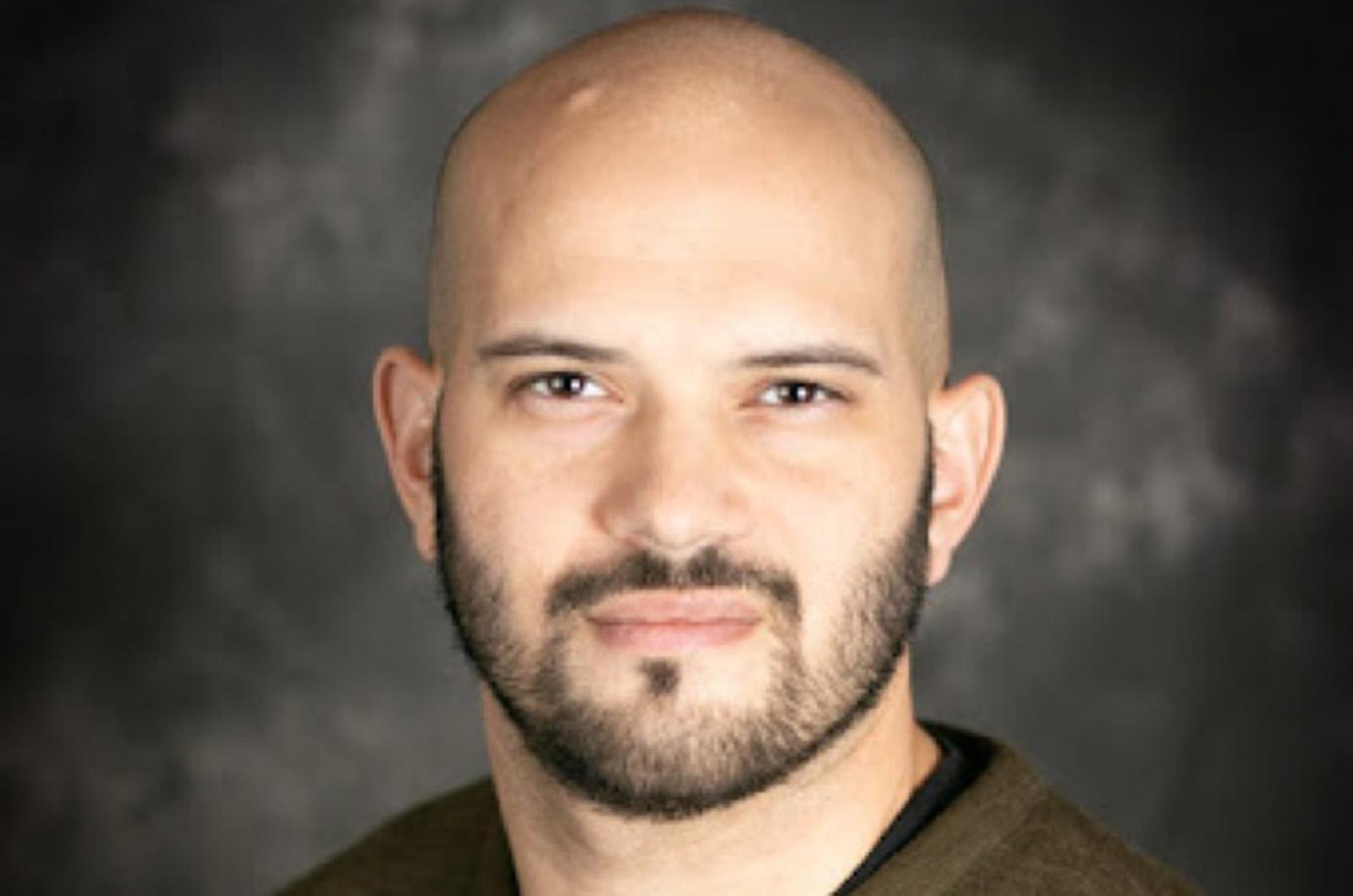

Harvard University’s Native American Program announced last week that its new assistant director will be Jordan Clark, a former history teacher and an enrolled member of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah).

The university’s Native American Program has existed in its current form, as an interfaculty initiative intent on supporting Native students and their communities, since 1998.

The university’s history with Native peoples, however, dates back to its initial 1650 charter to further “the education of the English and Indian youth of this country.” In 1665, Caleb Cheeshahteaumuck, a member of the Wampanoag tribe of Aquinnah, became the first Native student to graduate from the university as a part of the Indian College, forming what would become a long and tenuous relationship between Harvard and the tribe.

Mr. Clark said that when he starts his new role this June, he’ll be cognizant of the fraught history that has played out over centuries.

“There have definitely been some dark moments…but also opportunity for reconciliation,” he told the Gazette over the phone last Friday.

Mr. Clark gave the example of the first Wôpanâak-language Bible printed through the university press. Although the Bible was originally used to forcibly convert Wampanoag people to Christianity, it has become an integral tool to retrace the long-lost Wôpanâak language.

“Any time you’re talking about tribal history and larger colonial institutions, there’s going to be distrust and justified distrust,” he said. “The goal of the program is to show consistent action…not just saying, but consistently showing that you’re committed and open to dialogue.”

Mr. Clark is uniquely fitted to move between Harvard and the Aquinnah tribe, having grown up in Cambridge while spending summers on the Island with his family. His father is the vice chair of the Aquinnah tribal council, which he said granted him an informed perspective on the inner workings of tribal government.

Mr. Clark holds a bachelor’s degree in African American studies from Temple University and a master’s degree in international affairs from the New School. Prior to joining Harvard, he served as director of community programs for equity and inclusion at The Cambridge School of Weston, where he also taught Native American and African-American history, among other things.

“On a personal level, my experience as a teacher has granted me a lot of perspective for this role, as has understanding what pre-contact and contact looked like through my ancestors,” he said. “It’s been really powerful for me.”

He added that he hopes his leadership role will serve as an example to other young tribal members who might not have otherwise seen a place for themselves in an institution like Harvard. He will be working in a team of other educators and administrators with tribal backgrounds under the program’s executive director Kelli Mosteller, a member of the Potawatomi tribe.

When asked if he feels any weight or pressure to do the work justice, Mr. Clark thought for a moment.

“I’d probably be lying if I said no,” he said. “I’d love to think of pressure as opportunity for impact…I see it as something potentially really meaningful and impactful.”

Comments (5)

Comments

Comment policy »