With Island ponds suffering from the effects of development, the Martha’s Vineyard Shellfish Group is looking at an old foe in a new light. Over the past two years, the shellfish group has been studying the invasive wetland grass phragmites as a possible means for removing nitrogen from coastal pond ecosystems.

Phragmites first arrived on the Vineyard with the early settlers, who used the tall, sturdy reed to thatch their roofs. The plant is now widespread throughout the country, growing in monocultures and often taking a toll on plant biodiversity. Managing it is a challenge, since it reproduces through both seeds and rhizomes. Controversial herbicides are still considered the only effective means of eradication.

At the same time, Island ponds are experiencing varying levels of impairment as a result of nutrient overload, mostly in the form of nitrogen from septic tanks. Towns are exploring a wide array of solutions to the nitrogen problem, including expanded sewer systems. But alternative solutions, including oysters, which absorb nitrogen from the water, and denitrifying septic systems, are also part of the mix.

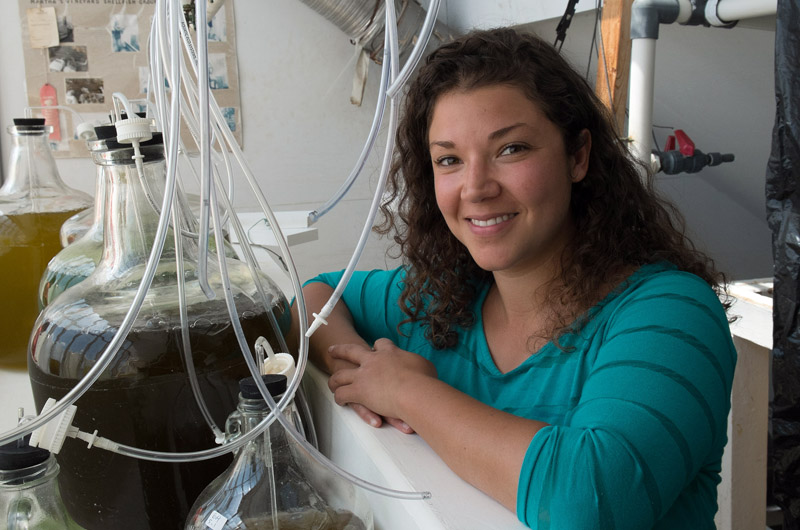

In 2013 the shellfish group received a grant from the Edey Foundation to begin studying the potential benefits of phragmites. Special projects coordinator Emma Green-Beach has beencollecting samples from around the Lagoon Pond on the Vineyard Haven side, and has determined that an acre of phragmites contains about 200 kilograms of nitrogen, or the equivalent of half a million cultured oysters.

“We could remove more nitrogen with phragmites than we can with an oyster farm,” Ms. Green-Beach said this week at the shellfish group’s hatchery, situated on a bank overlooking the Lagoon on the Vineyard Haven side.

Every year, the shellfish group raises tens of millions of oysters, clams and scallops, which are distributed among the Island towns. Most of the phragmites sampling so far has been done around the Lagoon, but Ms. Green-Beach plans to expand to Chilmark Pond, where phragmites is also abundant and shellfish can’t be eaten due to high bacterial counts.

Last year, most of the sampling was done in the summer, when the plant flowers. But Ms. Green-Beach hopes to start sampling much earlier this year, to see how much nitrogen the younger plants take up.

Samples are shredded in a wood chipper (provided last year by Mermaid Farm in Chilmark), and then further refined in a coffee grinder and sent to the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole for testing. Each test costs about $15, but many tests are required to gather enough data to be statistically useful. The shellfish group’s long-term vision is for a small Island company to harvest large stands of the plant and repurpose it as livestock feed, compost or biofuel.

This year Ms. Green-Beach will be sending some of the samples to a feed lab to get a better handle on nutritional value for livestock. Nathaniel Mulcahy, an expert in biochar, the carbon-rich byproduct of specially produced fuel pellets, has offered to donate equipment to make pellets out of phragmites.

Ms. Green-Beach sees phragmites as both a blessing and a curse. Its persistence means there is plenty to harvest from year to year. And unlike cultured shellfish, phragmites grows abundantly without the need for human labor. “We would never plant it,” she said, noting the animosity that many land owners and conservationists feel toward the plant. “It’s just about taking advantage of what’s [already] there.”

But in the public mind, phragmites is widely considered an ecological villain, and battles have played out across the Vineyard.

In Chilmark, a complicated legal dispute finally came to an end last year when a group of property owners around Squibnocket Pond was prevented from using the herbicide Rodeo to remove a large area of phragmites. At the request of voters, a special bill had been passed in the statehouse exempting the pond from the Pesticide Control Act of 1978, allowing the town to limit the use of chemical fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides and fungicides around the pond.

“For us to say, ‘Oh, it might be good,’ it gets people really fired up,” Ms. Green-Beach said. She agreed that there were sensitive areas where phragmites should not be allowed to persist. But for the shellfish group, the focus always comes back to nitrogen. “If the nitrogen keeps getting worse and if we can’t mitigate it, our ponds are just going to get sicker and sicker,” Ms. Green-Beach said. “And at some point we can’t make them better anymore.”

The shellfish group was recently denied funding by the Woods Hole Sea Grant program for the phragmites project, but that hasn’t stopped the research. With money left over from the Edey Foundation grant, the group plans to begin sampling in Chilmark, and to work with the Martha’s Vineyard Commission to map areas of phragmites around the Island. That will allow Ms. Green-Beach to extrapolate the plant’s nitrogen uptake ability for the entire Island.

Also this year, the Oak Bluffs conservation commission has been working with the shellfish group to determine what costs and permits would be required to harvest large amounts of phragmites. Conservation agent Elizabeth Durkee said the shellfish group would need to demonstrate that wide-scale harvesting would not harm the environment. She believed the only required permits would be orders of conditions issued by the conservation commission and the Department of Environmental Protection.

Mrs. Durkee said she was fascinated by the research and looked forward to seeing the results. “Now some real benefits of phragmites are beginning to become clear,” she said, pointing out that phragmites has also been shown to absorb more carbon dioxide than native salt marsh plants. The commission is helping the shellfish group draft a new funding proposal that involves several community partners.

Ms. Green-Beach was unaware of other groups that are focusing on phragmites and nitrogen, but she said several researchers have shown an interest in her work. She hoped to eventually partner with experts in nitrogen and phragmites to better understand how nitrogen cycles through the plant. She also planned to attend a four-day symposium on phragmites in Providence this spring.

So far, the shellfish group does not plan to publish its findings, since the shellfish propagation program requires so much of its time. “We like the idea of it but we are typically too busy,” Ms. Green-Beach said. “Our real concentration is to figure out, would it work for Martha’s Vineyard. Would it be accepted by our community.”

Last fall, Ms. Green-Beach set up a demonstration at the Living Local Harvest Festival, showing that a quarter-square-metre of harvested phragmites was equivalent to a jar of organic fertilizer, a liter of human urine, or roughly a dozen raw oysters. “Everyone’s first response was: Are you saying these are good?” she said.

Chris Neill, director of the ecosystems center at the Marine Biological Laboratory, who is not directly involved in the project, believed there was some real promise in using phragmites to absorb nitrogen. But like Ms. Green-Beach, he did not recommend planting any more of it. He also pointed out that harvesting phragmites was by no means a long-term solution to the nitrogen problem. “Next year that nitrogen will still be pouring into the estuary,” he said. Like many experts, he believes the ultimate solution will be enhanced wastewater treatment.

But if nothing else, the phragmites research is helping to raise awareness of the problem.

“The important thing to think about is how serious this nitrogen problem is and that all options should be on the table,” shellfish group director Rick Karney said, taking a break from his work in the hatchery, where the year’s first spawning of clams was underway. Motioning through the trees to the Lagoon below, he added: “The invertebrates that are supposed to be out here are not. The numbers are not there. The species are not there.”

One reason phragmites is so abundant near the water, he said, is that upland disturbances like houses and septic systems have created the habitat; the plant seems to thrive in nitrogen-rich soils. “You can remove it but it’s probably going to come back until all those other situations are fixed,” Mr. Karney said.

Comments (5)

Comments

Comment policy »