A removal for the first time of the restrictions which have prevented publication of any material regarding the types of planes at the Martha’s Vineyard Naval Auxiliary Air Facility, the activities at thee field, or the purposes for which it is designated, is marked by publication of an article, illustrated by drawings, in a recent issue of the Providence Journal. Some of the material in the article has been common knowledge on the Vineyard for a long time, but strict orders have prevented its publication. The Gazette had been told specifically that release of such information could not be authorized.

Incidentally, the article refers to the Vineyard “airport,” a term anathema to the personnel at the station.

The Journal article names some of the planes here, or to be used here, and makes it clear that both training and patrol work are functions of the station. The implication is also clear that training is particularly for pilots who will fly from carriers or small island bases. The article in full as written by Charles H. Spilman, is reprinted as follows.

Martha’s Vineyard, Mass. — Above the wind-riffled surface of Vineyard Haven’s harbor, where the tall sticks of coastal schooners lifted in other years, beat today the powerful engines of Navy war planes.

With emergency speed, but quietly, without upsetting the slow routine of Island life, the Navy has leveled an airfield on the sandy scrub oak-matted plain of what was a state forest. It is far from completed now, but planes have been flying there for weeks.

Small and Compact

The establishment is a subsidiary of the big naval air station at Quonset Point. The Navy has designated it as an auxiliary air facility, but it is actually an air station, small and compact.

The officer in charge is Comdr. Thomas Durfee, U.S.N.R., who came over from Quonset Point, where he was executive officer and, earlier, personnel officer. He has logged many years of Naval Reserve aviation since he commanded Navy planes at Chatham in the last war.

Commander Durfee’s office is on the ground floor of the administration and operations building. The windows look out across the sand flat where black paving forms a sharp geometric pattern of runways. Far down one runway stand two officers. One has a round, bright yellow paddle in each hand. The red crash truck is pulled up just off the runway.

Off to the right a TBF circles toward the runway. It is coming In a flat circle, wheels down and flaps extended, just above the trees. Now it hit’s the groove and comes straight in.

The signal officer extends his arms and the yellow paddles catch the sunlight. The big Avenger’s left wing dips slightly, but the paddles tell the pilot and he brings it up again. The officer cuts his right arm sharply across his body. The pilot drops the plane to the runway with the quick, bouncing landing which all planes must make in landing aboard carriers.

The plane runs only a few feet before the pilot pushes the throttle forward and the engine’s voice deepens and swells. With a short run the plane is airborne again. As the wheels lift from the runway, the pilot banks to starboard, as he would in taking off from a carrier, then flattens out and begins another circle.

Other planes follow the first, land, take off, land again. Each time they use only a small, marked area of runway, an area no larger than a carrier’s flight deck. They are units of a squadron which some day will be carrier based, which is drilling now for that time.

Swift Navy Fighters

There are Douglas scout bombers here, and soon there will be swift Navy fighter planes, all to be forged into fighting units for duty at sea.

But the air station has a dual role. Across the parking strip from the SBDs stands a row of patrol planes with pudgy, black depth charges racked beneath their wings. They sweep outward from this Island to patrol the ocean highways where the commerce of war moves in ships.

The activities of the station revolve around a vast, wood-beamed olive drab hangar, by a considerable Margin the largest building on the reservation. Although it can accommodate a good many planes simultaneously only those requiring major overhaul are brought into it.

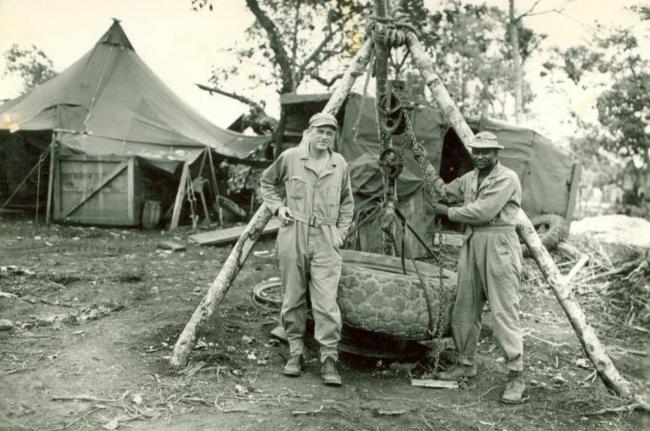

“On a carrier,” explains Commander Durfee, “the covered space, the hangar deck, is limited. On island bases just behind the assault lines there would be few hangars, if any. We try to duplicate here the conditions the men must work under when they go out.”

Near the hangar is the fire station, a bit of concentrated Rhode Island, as its personnel goes.

Farther along the new streets, yet unsurfaced, are bachelor officers’ quarters, the dispensary, mess hall and barracks. Quonset huts set on the periphery of the circle of larger buildings housing various departments.

In one, two Link trainers rock and twist and whirr and rumble, going through realistic maneuvers on their stubby yellow wings. Lieut. (j.g.) Arthur L. Johns, of Medford, Mass., once captain of a Harvard baseball team, is in charge. The Links are only part of the “synthetics” which the Navy will provide, the training aides which synthesize actual battle conditions. “I went through Harvard and Harvard Law School,” Lieutenant Johns says, “and this is more fun.”

Trying to Ride a Beam

At the far end of the building a young ensign plugs along, trying to ride a beam into Floyd Bennett Field. D. L. Flyers, aviation machinist’s mate second class, of Georgia, watches the progress of the “crab” which records on the chart on his desk the movements of the ensign’s plane.

Lieutenant Johns takes a spin in the other trainer with Walter Skees, motor machinist’s mate second class, at the desk. Skees is from Providence. When Chief Gunner’s Mate Robert W. Ketchum of St. Louis brings visitors in. Lieutenant Johns flicks a switch and steps out of the trainer. The altimeter shows it was 1500 feet, so there is some repartee about bailing out without a parachute. Johns and Ketchum have great plans for a target range and a good many other things which will build first rate fighters in a hurry.

Over near the BOQ, Hector Asselin of Warren sits on a platform, swinging his legs. He is on watch, but his duties are not arduous. A seaman first class, he keeps an eye on title pump beside him and sees that it goes on pushing water up to the high tank which towers over the other buildings of the station.

Despite all the planes on the parking strip and in the air, only one craft is assigned to the station itself. It is a rather forlorn little HE-1, a tiny Piper converted into a hospital plane to carry a single stretcher case. The man who flies it is spoken of by Commander Durfee as “our pilot.”

Comments