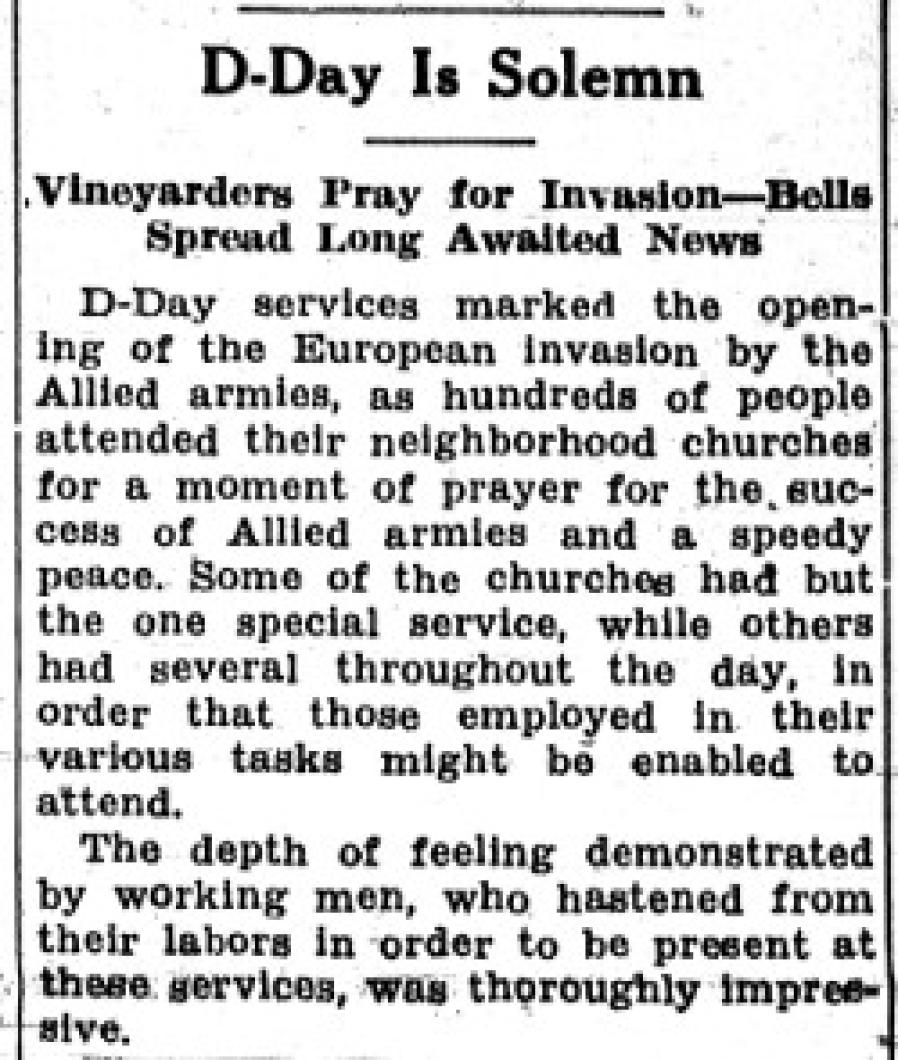

D-Day services marked the opening of the European invasion by the Allied armies, as hundreds of people attended their neighborhood churches for a moment of prayer for the success of Allied armies and a speedy peace. Some of the churches had but the one special service, while others had several throughout the day, in order that those employed in their various tasks might be enabled to attend.

The depth of feeling demonstrated by working men, who hastened from their labors in order to be present at these services, was thoroughly impressive.

Though they have no religious leader on the Island, Hebrew residents also gathered on Tuesday evening at the Martha's Vineyard Hebrew Center, there to observe the event with prayers for victory and peace, led by Max Miller, who presided as lay reader.

It was the ringing of the church bells in many of the Island towns which brought the first news of the invasion to all but the early risers who had already turned on their radios and heard the news for themselves. Although it had not been publicly announced that the Island bells would be rung in case of an invasion, the people sensed the meaning of the pealing of the bells, which had been rung the last time for other than a churchly message at the time Italy surrendered.

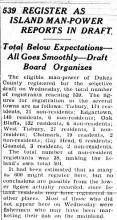

Although the exact figures are not available, and perhaps never will be exactly compiled, it is estimated that more than ten per cent of the Vineyard's year-round population is serving in the various branches of the armed forces and in the Merchant Marine. The reason why the figures are not available is because of the large number of volunteers, never registered with draft boards, and the transfer of local men to other boards, through circumstances which do not require a local report.

Scarcely a family is untouched by the war's demand for fighting men, and although there is little talk, when people meet, regarding the matter, Tuesday's demonstration revealed their feelings clearly.

Editorial: Lines Written on D-Day

Some must have known about it by 5 o'clock or maybe by 6, for Vincyarders are early risers, but it was probably 7 before the news spread generally. The church bells began to ring between 7 and 8, not in any special order, but spontaneously, as word went around and the the intention was translated into action.

The morning was one of the characteristically beautiful mornings of early summer when early summer is at its best. The sea was blue, the air was warm again after the recent chilly spell, for the temperature had risen in the night to around 55 or 60. The sun was bright, and shadows were splattered on the grass by apple trees and on the streets by elms. The sky was vast and clear blue.

Soon you could hear the planes from the Naval Air Station going about their ordinary business, and later in the day houses shook from heavy firing somewhere, perhaps at the anti-aircraft base on the Cape. These were the only warlike sounds and they seemed to have no direct relation to what was happening on the coast of Normandy.

The flags came out, not only on public buildings but in front of stores, on dwellings, and almost everywhere. They seemed brighter than on ordinary holidays. This was a holiday of a special kind, in that older, more solemn sense. People went to work, not exactly as usual, but they went. You could tell what they were thinking. There was a good deal of excitement, but it was not the noisy kind, and even the talk of good news seemed to the undertone of a prayer.

You could see men and women going into the churches for prayer. At the same time you could hear the noise of radios through opened windows, but there was nothing strange in that. Even the loudest, most continuously vocal radio did not seem strident or too much disturbance for the peaceful air, for it was bringing news and hope, the substance upon which the payers of the day were based.

Such a bright Island day, so much sunlight and-warmth, so much of the blessing of heaven - if there could be an omen one believed this might be it. There were no crowds, there was no yelling. What needed to be said publicly, the church bells said here and there, and not a few Islanders had their first news of the invasion from the sound of the bells.

This was D-Day on the Vineyard, and weeks from now we shall know what it was like for some of the Island boys who crossed the English Channel by sea or by air to fight for freedom in the world.

Comments