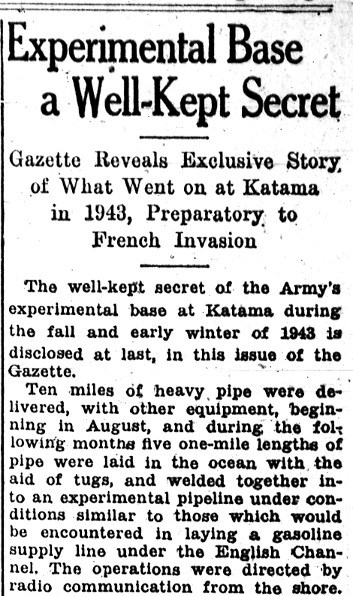

The well-kept secret of the Army's experimental base at Katama during the fall and early winter of 1943 is disclosed at last, in this issue of the Gazette.

Ten miles of heavy pipe were delivered, with other equipment, beginning in August, and during the following months five one-mile lengths of pipe were laid in the ocean with the aid of tugs, and welded together in to an experimental pipeline under conditions similar to those which would be encountered in laying a gasoline supply line under the English Channel. The operations were directed by radio communication from the shore.

Following the laying of this pipeline, an advance version of the line ultimately laid under the Channel for the supply of gasoline to the Normandy invasion, experiments were carried on to test the practicability of connecting sections of pipe under the water and on the surface.

The Gazette some time ago initiated steps to obtain the inside story of the Katama operations, and the following clear and complete statement from the office of the Chief of Transportation of the Army Service Forces has now been made available for publication because of the intense local interest.

A Transportation Corps Project

The project originated with the Army Transportation Corps and was carried on under the direction of the Engineer Board. Col. John W. Wheeler, formerly commissioner of the Department of Public Works in Indiana, who had been assigned to an important part in the construction of the Alcan Highway and the Burma Road projects, was in charge of the experiments which lasted until mid-December of 1943.

The official statement follows:

Installation and use of underwater pipe-lines in the English Channel to supply Allied Forces on the continent with gasoline and oil, announced recently by the British, was an operation contemplated and tested by the American Army back in 1942, the War Department revealed today.

While there is no disposition on the part of the War Department to detract from the accomplishment of the all-important undertaking by the British, the story of American planning and experimentation is made public as a matter of record.

To the Army Transportation Corps of the Army Service Forces goes the credit for initiation of this project back in 1942. Col. John H. Leavell, an oil operator of long and successful experience, who was the directing the Transportation Corps' work in connection with the handling of petroleum products, began toying with the idea in the summer of that year.

Colonel Leavell, who since has retired and accepted an important foreign post with the State Department, obtained the support of Brig. Gen. Theodore H. Dillon, (retired) Deputy Chief of Transportation, who had fostered a number of other highly important developments in wartime transportation equipment, notable among them the amphibious truck, or Duck. Together they obtained the approval of Maj. Gen. Charles P. Gross, Chief of Transportation, and began a series of experiments to test the practicability of the idea.

New Problems to Be Faced

Under-sea pipelines were not a new idea. They had been used in many places to discharge tankers off-shore when no harbors were available. They had been laid under rivers where the currents were swift. New problems, however, arose from the fact that the cross-channel line would be possibly thirty miles long and would have to be strung in water as much as 150 feet deep.

Initial experiments conducted by the Transportation Corps during the winter of 1942-1943, which included the development of a flexible joint, were considered sufficiently satisfactory to warrant pursuing the matter further. Accordingingly, preparations were made for the laying of an experimental pipeline under conditions similar to those which would be encountered in the English Channel. A contract was made with the Atlantic Pipe Line Company to aid in the work.

Since the construction and operation of pipelines for the Army is a function of the Corps of Engineers, it was decided that the tests should be conducted under the direction of the Engineer Board. A representative of the Atlantic Pipeline Company and Colonel Leavell then brought the problem to the Petroleum Distribution Branch of The Engineer Board for discussion.

The members of the technical staff of the Engineer Board did not concur with the idea of making pipe connections under water but did favor surface connections. However after further discussions it was decided that both types of pipe connections would be tried and the project would be tested under the direction of the Engineer Board.

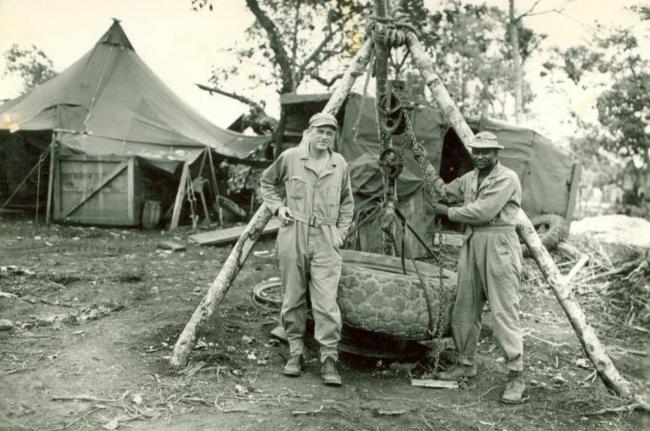

A stretch of beach on Martha's Vineyard, near Edgartown, was chosen as the site of the experiment, and the assembly of equipment and material began in August, 1943. Ten miles of 4.5-inch O.D. extra heavy pipe to be used for the tests were delivered at Martha's Vineyard. Pipelayers, cranes, trucks and other shore equipment were provided, and two tugs were engaged to tow the lines of pipe out to sea.

One of the Basic Problems

One of the basic questions which the tests were designed to answer was that of the effect of friction set up by drawing the long lengths of pipe over the beach and the ocean floor. A 3,000-foot length was towed over a fifty mile course without undue abrasion and without opening any of the welded joints.

Five one-mile lengths of pipe were assembled adjacent and normal to South Beach which was the site of the launching. The plan of operation called for controlled movement by radio communication between the tug drawing the pipe and the personnel on shore.

The first length of pipe was towed into the ocean and stopped so that the end could be welded to the second one-mile length. This process continued until the five mile lengths towed into position. When th last mile was added three tow boats were required to move the five mile lengths.

After these tests were completed, experiments were undertaken to test the practability of connecting two sections of pipe under water and on the surface. The under water test was successful in shallow water but was not suitable for the depths that would be encountered in the channel crossing. The attempts at surface connections were slow and beset by a number of difficulties.

According to recently published reports, interest in a cross-channel pipeline developed in England also in 1942, when plans for the eventual invasion of the Continent were being formulated. Experiments carried on under joint United States and British auspices developed a flexible pipe similar to the casing of a submarine electric cable, which could be wound on a drum and unwound as the drum was floated to sea. The first line is reported to have gone into operation on Aug. 12, 1944.

Comments