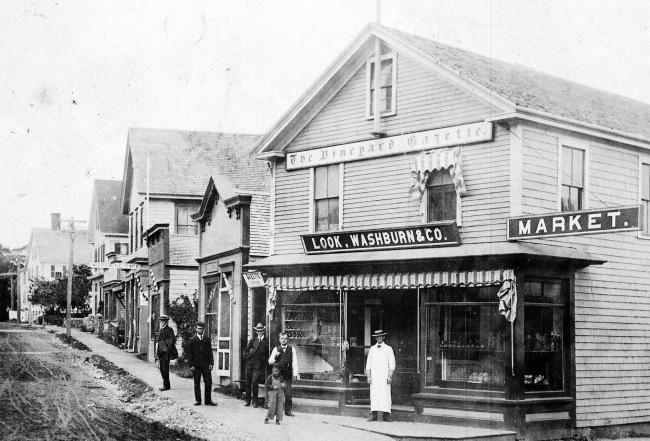

Everything, including our culture, was very old fashioned in 1920. The location of the Gazette office, even, was on the second floor of a building, long since replaced by the liquor store and real estate modernities at the Four Corners, so called, at Main and North and South Water streets in Edgartown.

There had been earlier Gazette offices, but no one remembers what they looked like. One finds historical verification for this one in the Martha’s Vineyard Directory of 1911 which says: “Newspapers, Vineyard Gazette; Charles H. Marchant publisher, cor. No. Water, cor. Main (see Page 172).” The page referred to begins with the lines “Established 1846” and ends, one would say adequately, “The Gazette Covers the Vineyard.”

But of course there are many other references, many of them much earlier, and photographs to amplify. The photographs may be confusing because some show an outside staircase on the Main street side, and others show a rather different outside staircase on the opposite side. This was the one we knew in 1920. It was the one that the late Edwin Bryant Treat, who kept a tutoring school at Eastville in the summer, climbed up briskly, whistling a far-carrying tune all the way to the top, and Lawyer Douglas took the first few steps to utter grimly, “I’m going to lick the editor,” but by the time he had reached the upstairs doorway he had become companionable.

The Gazette office itself accommodated a soapstone sink with paste pots, half a ton of pea coal, a station agent stove bound with wire around its cracked middle, and pretty much the history of printing represented by type cases, tall stools for two girl compositors, a job press run by foot power, and the never to be forgotten Fairhaven press. It was powered by a hand crank on one side. Sheets of paper were fed around a cylinder, the proudest part of the press, which surprised visitors by turning twice in order to produce a single impression. This was because it was a two-revolution press.

Every sheet must then be fed through again, two more turns of the cylinder, in order to emerge with pages completed on both sides. The press must be turned moderately and considerately, never impetuously, or the mechanism would jump out of its tracks.

The Gazette did not use store-bought paste. It mixed up its own from gum trajacanth and water. When Walstein Osborn went to the drug store, at the place where they now sell fudge, he would ask for a half pound of “that stuff.” Gum trajacanth, specifically, is not in my American Heritage Dictionary, though I consider it part of my heritage as it was of Walstein Osborn’s.

The Gazette was surrounded by essential business of the town, some of which were combined with the arts. One of these was Smith, Bodfish, Swift Co., which dispensed meats and groceries on the street floor, under the able and genial management of Napoleon J. Berube and Rosario Carroll. Periodically, it seemed, successful grocers entertained a vision of getting together and enjoying the major share of the Island grocery business. Such plans never worked.

On the corner of Main street opposite SBS and the Gazette was the Home Club in which retired whaling masters and men of wealth and position shared a comfortable relationship. But the retired captains became fewer and more choosy usually spending their evenings around the stove in Will May-hew’s hardware store or Jo King Silva’s shoe store. And the prominent men of affairs who came for summer vacations were soon numerous enough to foster groups or even colonies of their own. Evolution, one of the most divisive of forces, was at work.

Down Main street a bit from the Home Club was the meat market and grocery store of John Bent who, like all the grocers, catered to the relatively constant demand for the constituents of New England boiled dinners. One product of John’s art was a choice of signs identifying his business. “Vegetables from Bent’s Farm Daily” was his favorite slogan, and in one of his signs he had a cut-out figure of himself pushing a wheelbarrow heaped with vegetables.

Boys once raided John’s melon patch opposite the West Side cemetery. He had them in court, but turned his mind again to art. He cut out and painted the wooden figure of a policeman bearing a sign of warning over one wooden shoulder. Something kept the boys away, and perhaps it was the policeman.

One fall John dug a trench in his yard, filled it with ashes, cement and sand, and let it all soak until solid. Out of the resulting block lie carved the figure of a plump-bellied nymph blowing through an upraised likeness of a shell trumpet. Eventually this statue was acquired by the late Marshall Shepard for the Dukes County Historical Society, but apparently some prissy factotum threw it out.

John’s good humor was immense, but illness overtook him. His last cement work was his own gravestone, which may be seen on the Cooke street side of the cemetery, well up toward the school grounds. “Pray for the soul of John Bent,” he had inscribed neatly in the cement, and some of us still do, as passing by, we notice his self-made memorial.

Also below the Gazette office on Lower Main street were the bakery of Mrs. Pillsbury who would sell her delicious bread only to customers of her own choosing; and the Fisher grocery store, and Capt. Zebina Godfrey’s haberdashery from which he sold the Rev. Howard P. Davis a blue serge suit after Betty had told me it was not my style.

The Gazette office was surrounded by the simple but essential businesses of the town. One of these was C.A. Dexter’s barber shop, where the barber shop deli now is. Mr. Dexter, on account of the convenience of his initials, was generally called “Cad.” This also had the advantage of distinguishing him from Tom Dexter, who represented the state constabulary and later served as sheriff for many years.

Cad Dexter’s artistry was demonstrated by a mammoth still-life which occupied one entire wall of his shop. It could be called an inclusive work, for Cad had painted into it all local fruits and vegetables in their richest coloring, and some exotics suitable to a port of shops that had visited many seas. This great still-life could have been purchased at one time for a few hundred dollars. I hope no harm has come to it.

Across Water street, where the drug store now is, the ample quarters were occupied by Ed Nichols, the Sanitary Barber. His name and his claim were inseparable.

The building was then owned by William P. Bodfish of Vineyard Haven, who was endeavoring to sell it for $5,000. The price was right but the money was too much for the times.

The upstairs was occupied at one time by the customs house and, through the years’ by the offices of doctors who came and went. A friend of one of them, dropping in for a social call, took down one of the imposing medical volumes from the shelf and found that the pages were entirely blank. This episode is recorded here as a symbol of customs that were.

Many oldsters can recall how the late Chester E. Pease sat in the window of the dress shop that was one of the successors of the Home Club. In winter the shop was almost bare except for the wired, naked dress forms, and Chester Pease viewing the outlook up Main street.

The bank, of course, was on the opposite corner, anchor of the Four Corners, and the president was Beriah T. Hillman who had come down from Chilmark one election time. He was also a G.A.R. veteran, a town and Island father, and a patriarch whose appearance matched his status. He represented a small town figure once typical over the country at large, but no longer so.

Behind the bank was Jo King Silva’s shoe store where. of an evening, many congenial townsmen gathered to smoke their pipes and chat. Will Mayhew’s hardware store on North Water street was a similar gathering place with its own clientele. That was an era when wives and children stayed home, and men went out in the evening. Later the order was reversed. The men stayed home, the boys’ went out, and the wives were not infrequently at club meetings.

Returning to Main street and heading uptown, one came to Billy Mendence's two shops, tobacco and confectionary and the shop of Tyler the Taylor, a sardonic and knowledgeable figure who had a bet with the town’s undertaker as to who would succumb first to a wasting disease.

From all this, so, nicely centered in interests and character, the Gazette, rather reluctantly, moved away. The size-and weight of linotypes and printing presses of modern necessity had a lot to do with it.

The initial move was to the Summer street building which had once been a grocery and later the establishment of a watchmaker and jeweler, roughly opposite what is now the Charlotte Inn. The building receded from the street like a bowling alley in proportions, incredibly long and narrow. One of its imperfections was that the press a second-hand Whitlock which followed the doomed Fairhaven, had to be stopped every time the telephone rang.

Various odds and ends from the clockmaker’s day had remained on the premises and in time a well-dressed visitor came to inquire about them. We inquired about the condition of Mr. Shepard, the jeweler, and our caller made a reply which I have always considered ideal for one of Mr. Shepard’s profession: “He has climbed the golden stairs.”

In that building, which never served us well, it was occasionally necessary to cut a hole in the clapboards to allow some piece of machinery to stick out.

The latest move has taken the Gazette at last to a home with room for everything despite the pursuing spectre. Growth. So it starts afresh - the first time it has ever started afresh - and the spirit of Capt. Benjamin Smith who, it is believed, built the main building about 1760, may be induced to drop in and make himself, or itself, as comfortable as any Revolutionary hero ought to be.

Comments