Linwood J. Belisle of Edgartown — you’ve seen his Lin’s Lawn Mower Repair shingle on the Vineyard Haven Road — enlisted as a parachuter 42 years ago looking for adventure and some extra cash. “Eldon Willoughby and I, we went up to Boston together to register, and there was this big poster of the parachuters, and it looked exciting, and then Eldon says, ‘Hey, look, the parachuters get an extra $50 a month,’ so that’s how we decided,” Mr. Belisle said the other day sitting at the kitchen table of his Edgartown home.

That was Sept. 2, 1942, and Mr. Belisle was 19 years old. Twenty-one months later he was among the elite corps that dropped in on Normandy in the climactic campaign of World War II.

Actually, Mr. Belisle was dropped in water, not land. The Germans flooded large amounts of landing ground, and Mr. Belisle spent the first hours of the invasion of Normandy in deep water, kept afloat only by his parachute, like the flower of a lily pad. He drifted ashore and cut himself loose. It was in the still dark of early morning; the sounds of the night were of German machine-gun fire.

As Mr. Belisle was drifting into shore he heard a man in a tree crying for help. By the time he reached water shallow enough to stand in, the crying had stopped.

Mr. Belisle does not attempt to interpret what happened. The soldier may have been saved, or he might have died in that tree. It was a chaotic night and a chaotic day. From those experiences, chaotic memories are engraved, and from the confusion comes little opportunity for interpretation.

“We trained at Currahee Mountain, in Georgia,” says Mr. Belisle, wearing the hat of the 101st Airborne, Screaming Eagle division. If you’ve gone to Mr. Belisle to have your lawn mower fixed, chances are he was wearing that hat, its parachute wings engraved with Currahee.

“It’s Indian for ‘We stand alone,’ ” says Mr. Belisle.

Mr. Belisle thumbs through a World War II book, one of many in the house. “Over-paid killers,” he says, pointing to a heavy black type two inches high. “That’s what the Germans called us.” The reference is to the extra $50 a month American soldiers earned, Mr. Belisle explains.

Along with the books are the medals: two Bronze Stars, three Battle Stars, one Spearhead, two Presidential Unity Citations, the Combat Infantry Badge. There’s more, but it’s tucked away in another room.

“It is not the most important thing of my life,” says Mr. Belisle. “I’ve had a very full life, commercial fishing and working on a yacht and working as a carpenter and a mechanic, and now the lawn mower repair business.”

But clearly, his war experience remains important to Mr. Belisle. He reads his Screaming Eagle Magazine carefully, and keeps up to date with his war buddies by telephone calls and visits. For Memorial Day he went to Washington, D.C., and Arlington National Cemetery.

He pulls out of a closet a bright red flag with a white circle containing a black swastika. It’s an alarming sight.

“I got this off a Nazi headquarters in Holland,” says Mr. Belisle. On it are names, some of men who died in combat, some of men who are Mr. Belisle’s close friends today.

“Now, thus guy here, Sleepy Russell, I’ve been Sleepy since the war.” On the Nazi flag is written “W.E. (Sleepy) Russell, Bonham, Texas.”

There’s also Cheery McAdam and Brandy Demback.

“He got killed in Holland,” says Mr. Belisle, pointing to Mr. Demback.

“Everybody had a nickname,” he says. “Everybody had buddies. You just kind of buddied up with somebody. We had close friendships then, and they stuck because we had a common bond.”

On the kitchen table are World War 11 books: Rendezvous with Destiny. Directory of the 10 1st Airborne. On a side table in the living room is a book entitled Paratrooper!

Mr. Belisle spent his first 24 hours of D-day hiking though 18 inches of water.

“1 figure here I am, from Martha’s Vineyard Island, and I’m going to drown to death,” Mr. Belisle says, laughing.

But he’s joking. “We never had time to think about dying. I was lucky. 1 was the only guy from my unit never hit.

“We knew what we were doing. We were fighting to

keep the country free. We were fighting to keep Hitler from taking over the world, which 1 don’t think he would have done.” Mr. Belisle pauses.

“I still think Pearl Harbor was a bitter thing for this country.” He’s asked to explain.

“I don’t like to get into politics too much,” he says. “I’m just Lin Belisle.” A non-political guy who risked his life for this country.

Forty years ago Ted Morgan, the Edgartown selectman and retired Air Force colonel, was trapped in a tree in Normandy, France, his parachute chest strap pushed to his throat. His parachute was tangled in tree limbs like so much errant fishing line around a boulder. The sounds of the night were of gunfire and roaring aircraft. Mr.

Morgan dropped his knife in his efforts to free himself, and thought about death.

“We thought about death all the time,” Mr. Morgan said the other day as he sat in the serene garden of an Edgartown house.

Forty years ago, Mr. Morgan heard a rustling under the trees.

“Thunder,” he whispered. And he waited, his hope for life embodied in that one whispered word. “Lightning,” came the response.

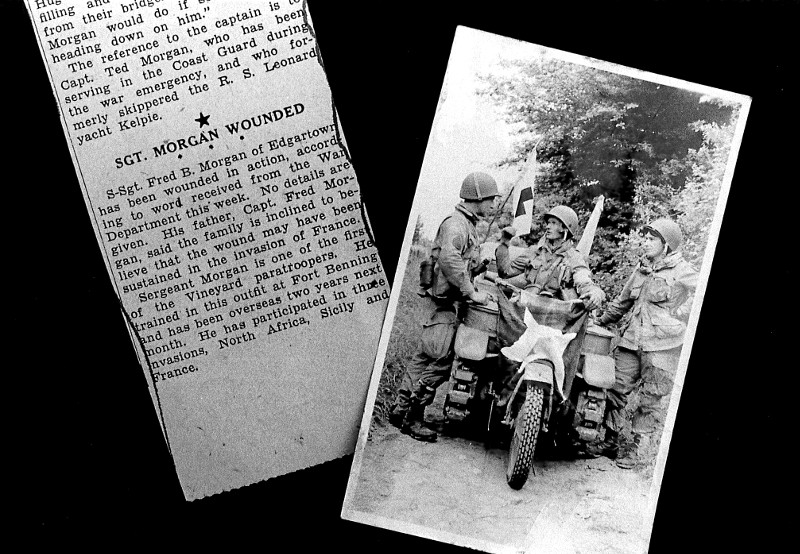

And it was then that Fred B. Morgan Jr., a native son of Edgartown and a staff sergeant of the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment of the 82nd Airborne, knew that the noises below were of friends, not enemies.

D-day, World War II: Americans thought in different ways then, says Mr. Morgan. There was life and there was death. There were friends and there were enemies. The fight was to preserve life.

But in the fight for life, death abounded.

“You see people falling all around you, and you figure that the law of averages is against you, and that you may be next. So you try to dig your hole a little deeper, and hope it protects you,” says Mr. Morgan, speaking as if the war were on, oblivious to a mosquito swirling around his 82nd Airborne hat and weathered face.

The issues were clearer, the messages more straightforward then, as Mr. Morgan tells it.

General James M. Gavin stood on the hood of a Jeep, before the men of the 82nd on the eve of D-day and said, “Look to your left, and look to your right, because two of every three of you are not going to make it.”

Mr. Morgan heard those words. In the center finger of his right hand he carries a piece of shrapnel from the invasion that began World War II; in his mind he carries the knowledge that 600 men he knew died in World War II.

The purpose was clear, too. “Hitler was going to take over England, and we were there to stop him. Hitler had to be defeated, and we were the ones to do it.”

Mr. Morgan speaks of World War II with the perspective of having been part of the military establishment during Viet Nam.

“During World War II, the civilians believed in the military. There was an esprit on both sides. We were unified. Everyone realize it was a war that had to be fought. It’s very different from Viet Nam. All we did lose 57,000 people. It was an exercise in futility.” he says.

Mr. Morgan has not been back to Normandy since he was dropped into its fields by parachute 40 years ago. He wants to go back.

“I think about it quite often. I’m proud I became a paratrooper. I’m proud I served. I’m proud I fought with the people I did. It was a team effort, and that’s what made it possible,” he says.

Mr. Morgan spent four months in England preparing for D-Day, and he says the jump into combat, one of four in his war career, was “the highlight of my life.”

He thinks that Americans born after World War II don’t understand the importance of the conflict within the proper historical perspective. He wished the story of that war received more attention in the nation’s schools.

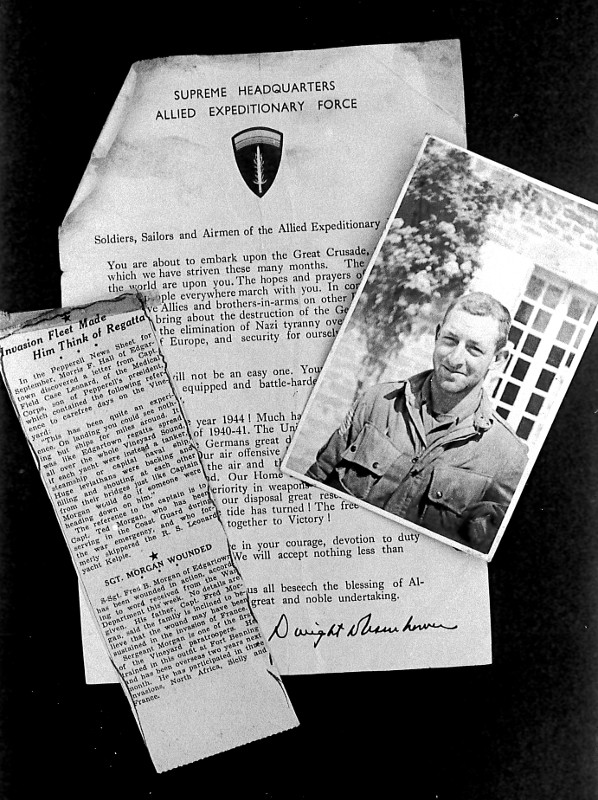

How many Americans today understand the significance of Mr. Morgan’s honors? There’s parachutist’s badge, with four stars for combat jumps; the combat medical badge; Presidential unit citation; a Bronze Star medal; a Purple Heart; a European Theatre of Operations ribbon with an arrowhead representing membership in a troop that spearheaded the invasion, a silver star for five campaigns and a bronze star for a sixth; and five overseas stripes.

He handles with pride an old Gazette clipping about his hero’s return to Edgartown; a photograph of a uniformed, young Ted Morgan, slightly faded; a copy of a speech from Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, with a simple message of what the fight was about.

After the drop into Normandy, Mr. Morgan looked for Nelson Bryant, another Vineyarder, later to become his brother in law. He couldn’t find Mr. Bryant, who had been evacuated after being shot, although he returned later for more combat. The two didn’t meet again until both were back on the Vineyard.

Mr. Morgan is fiercely patriotic. He is ready, still today, to die for this country.

“The United States,” says Mr. Morgan, “is the best damn country in the world.”

Comments