For the sheep grazing in pastures above Vineyard Sound, the patches of weathered canvas beating toward Holmes Hole were barely worth a glance away from meals of September grass. Farmers, townspeople and public officials, however, greeted the approach of some four dozen English-flagged vessels with a bit more alarm.

In 1778, coastal fishing, whaling and trade sustained much of the Island, a community of just under 3,000 people, as did farms that raised livestock and vegetables. Although residents were somewhat divided on the politics of the Revolutionary War, the proximity of the conflict was cause for concern among loyalists and rebels alike.

History shows that whether the combat was at home or abroad, what the Vineyard has often had to think about first and last is its own well-being. The Island, after all, lies in the North Atlantic all by itself, and in wartime it has been largely undefended, and sometimes indefensible.

By the fall of 1778, the capture of ships in Island waters was a common occurrence. The British government had decided to “punish the rebels” by blockading certain Massachusetts ports, according to Dr. Charles E. Banks’s History of Martha’s Vineyard. Employing schooners of the sort often used by Islanders, the Royal Navy seized cargoes and vessels near Vineyard harbors, curtailing the livelihood of mariners and depriving people on shore of many goods and materials.

“Last week [an American] ship of 300 tons, loaded with coal, potatoes, porter, raisins, dry goods and 33 live hogs was taken near the Vineyard by a schooner and several whaleboats, who lightened her of half her cargo and then carried her into [New] Bedford. She had about 20 hands and was bound to Boston but had been to New York,” reported the Newport Mercury. As the colonials attacked British vessels in return, tension rose along the Sound.

“A gentleman who left the Vineyard on Monday informs that some [American] cruisers or privateers had [diverted] a ship of some 300 tons [into the Vineyard], loaded with sugar, rum and Madeira wine, bound from Jamaica to England, and they had taken three or four more which were to make the first port they could,” the Mercury said. “The above ship was to be carried into Dartmouth [with] the first wind.”

The Massachusetts government soon decided that the Island was “so situated that it must put the State to great expense to defend it should our Enemies make that an object of their attention,” and that “the removal of the Inhabitants of said Island to the main would be attended with many and great Inconveniences to them and cost to the State.”

A garrison of 500 soldiers was reduced to 25 militia troops. In plain terms this meant abandoning the Vineyard to its fate.

As the disruption of commerce in the area increased, so did the trepidation of residents. When the British force anchored that September in Holmes Hole, now Vineyard Haven harbor, the anxiety of Islanders was justified. Commanded by Major General Charles Grey, the squadron of ships and tenders was on a mission to gather supplies for royal companies stationed in Newport.

“General Grey, commanding a detachment of his Majesty’s Army, arrived at Martha’s Vineyard Sep’r 10, 1778,” wrote militia Col. Beriah Norton in a statement about what came to be known as Grey’s Raid, “when I waited on him on board ship & agreed to deliver him 10,000 Sheep & 300 head of Cattle, the General informing me at the same time that payment would be made for the Same. The General then required the Stock to be brought to the landing the next day which was punctually Comply’d with.”

But not punctually enough.

“They promised each of these articles should be delivered without delay,” wrote General Grey, “and afterwards found it necessary to send small detachments into the island and detain the defected inhabitants for a time in order to accelerate their compliance with the demand.”

On Sept. 11, as the great arkload of sheep and cattle were being herded toward the landing, General Grey’s detachment set out across the Island to make sure the British were getting everything the Vineyard had to offer. Cows, pigs and sheep had been tethered to trees in the scrub brush, where many militia armaments were also concealed. One girl is recorded as taking her prize cow into the attic of the family home, and locking the door behind them. An elderly Islander allowed the British only so much latitude. When a half dozen soldiers reached the up-Island cottage of Patience Hathaway Dunham, wife of Joseph Dunham, they rounded up all her livestock before approaching her to capture a pig hidden behind her petticoats.

“Away with ye, cursed seed of the oppressor, despoilers of the widow and the fatherless!” she cried while brandishing a broomstick. “Take what ye have of mine and begone! But this is Josey’s pig, and not a hair of him shall ye touch!”

According to the popular account, the soldiers eventually gave up and departed with the pig unharmed. But they were not done. They burned a salt works, a brig, a schooner and 23 whale boats in two towns and took with them salt, planking and a thousand pounds in currency. They finished off the raid in merry fashion:

“The British caryed off and Destroyed all the corn and Roots two miles around Holmes Hole Harbour,” wrote Joseph Otis of Falmouth. “Dug up the Ground everywhere to search for goods the people hid: even so Curious were they in searching as to Disturb the ashes of the Dead: Many houses had all Riffled and their windows broke.”

Despite many appeals by letter and a two-year trip to England by Colonel Norton, the Island never received that promised payment for the goods and animals taken by the British. The value of the appropriated property was estimated at 28,186 pounds, according to one report of the raid.

Close to 100 years later another, more distant war caused widespread concern across the Island, this time for the lives of men in battle on the mainland, as well as for the vitality of maritime activities on the Island.

Some 240 residents served in the Union Army and Navy during the Civil War, nearly 50 more than required by law. The Vineyard feared not only for the men who went to fight, but also about those who might be called up unfairly or unnecessarily.

In June of 1864, battlefield losses for the Union Army had risen sharply from the earlier years of fighting, and the need for recruits was enormous. An Edgartown man, Richard L. Pease, noticed a problem with the state system of conscription — nearly half of the men who enlisted in Edgartown were not credited to the town, which had paid bounties to many of them to sign up.

A former schoolteacher who was then clerk of the County Court, Mr. Pease feared this discrepancy might place the Island below the state quota and result in demands for more volunteers. With Henry L. Whiting of West Tisbury, a topographer working for the Federal coast survey, and William Sturtevant, minister of the West Tisbury Congregational Church and representative to the General Court, Mr. Pease incited a statewide draft protest that led to a change in the Massachusetts rules of conscription. Henceforth recruitment efforts would credit the towns from which the recruits had come.

With whaling vessels all over the coast threatened by Confederate raiders, many Vineyarders recognized the danger to the most important maritime industry of the time. Indeed, there was to be a steep and swift decline of the Island fleet after the war, and in the number of vessels belonging to other fleets that Vineyarders could captain or man. The federal government sank scores of New Bedford whaling ships at the entrance to Charleston harbor in a futile effort to block southern shipping. And one Edgartown whaling ship, the Ocmulgee, was sunk by the Confederate raider Alabama, which burned over 50 Union merchantmen, about 15 of them whalers.

In 1850, the whaling-related operation of Dr. Daniel Fisher employed dozens of residents in such pursuits as a whale oil refinery that was the exclusive supplier for all the lighthouses in the nation, the largest spermaceti candle factory in the world, a hard-tack bakery to supply whalers, a wharf to service whaling ships and a grist mill in North Tisbury. Dr. Fisher also held part ownership in several whalers.

Before the war, his business each year produced around 118,000 pounds of candles and 13,200 barrels of strained and refined oils, for an annual value of more than $280,000. Dr. Fisher himself was reported to earn over $500,000 a year from his various enterprises.

The decreasing demand for whale oil after the discovery of petroleum in 1859, as well as the loss of so much of the whaling fleet in the war, disrupted both the source and the market for most of his products. As with the whaling industry in general, Dr. Fisher’s operation never recovered after the war.

Nearly 80 years later, the community again was given reason to fear for its sons and daughters at war, as well as its own safety in the North Atlantic. Hundreds of Island men and women fought in World War II, from students just out of high school to married people with young children.

Concerns for friends and family in the service were paramount for residents who stayed at home. But day to day, there was nearly as much concern and confusion about wartime activities on the Vineyard.

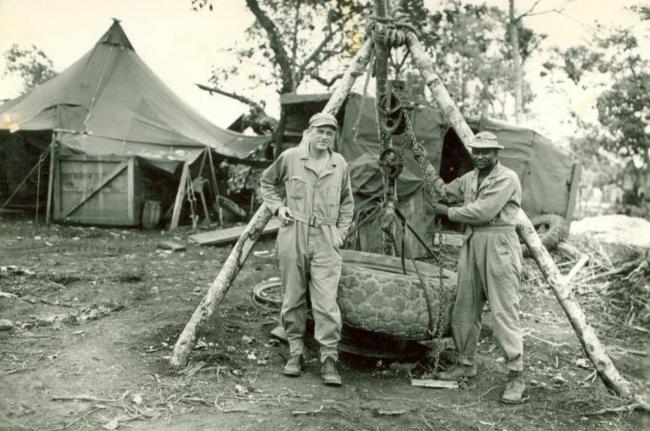

The Army and Navy took possession of miles of beaches, plains and woods, establishing an aerial gunnery range and experimental base at Katama, where miles and miles of metal pipe were fixed together and towed out across the ocean bottom to see if an underwater fuel line could connect Britain and France after D-Day. (The Allies wound up using flexible pipe instead.) An early radar station was built near Peaked Hill in Chilmark and a flight and combat training base, the Martha’s Vineyard Naval Air Station, was built on more than 600 acres of the old great plain in the center of the Island. This station is now the Martha’s Vineyard Airport. Mock landings were conducted along East Beach and the south shore against defenders in bunkers and entrenchments.

Edward T. Vincent, a farmer at South Beach near the Katama base, was less than pleased when the Navy commandeered a tract of his land without notice or legal formality of any kind, according to a newspaper account at the time. Farmland and fences were destroyed, and the landscape was altered for military use. Mr. Vincent made several attempts to drive into the field, aiming to tend his cattle. He was ordered off the property as a trespasser.

“There was quite a set-to,” Mr. Vincent said after his last attempt to storm his own land. He added that while he may have won the argument on merit, the Navy had more guns and manpower and so held their ground. However, no one threatened to shoot him, he said, a distinct gain from an earlier experience when he went to retrieve his cows.

Another Katama man recalled nearly engaging in a brawl with guards on the way to left fork, where he was stopped at gunpoint on his bicycle. He forgot his clearance papers at home, and the soldiers judged from his mild French Canadian accent that he must have been a saboteur.

Information about military endeavors was hard to come by, and it was a common Island pastime to speculate on the activities of friendly forces around the Vineyard — and enemy forces too, some thought.

“In those days, if you saw somebody around up-Island here that you didn’t know, right away it was a spy,” Everett Poole of Chilmark told Martha’s Vineyard Magazine in 1995. “Some guy just walking around or something. They made up convoys to go to Europe right off Noman’s. So you’d see a lot of merchant ships out there, and every day there’d be more and more, until they took off. So it wasn’t unusual for people to suspect that.”

A rumor circulated for months about a German submarine that sank off the south shore, supported by a second tale of two Germans coming ashore in life rafts. While neither rumor was confirmed, Islanders learned after the war that a Navy report gave serious consideration to the possibility that a submarine may have damaged a merchant vessel near Vineyard Sound.

“But whether it’s true or not, I don’t know,” Mr. Poole said. “Every once in awhile you’d see a merchant ship sinking off here. You’d see her burning. You knew there were submarines close by. And they were always concerned they were putting people on the beach, because it was an ideal place to watch the convoys build up. Whether they ever did or not, I don’t know. I remember two different pairs of men that were reported as suspicious here once during the summer.”

Training at the Navy air base was a perilous business; it got more perilous as the war dragged on and it appeared that the Allies might have to take Japan an acre at a time. Training was speeded up and the loss of life grew terrible: Forty trainees died in the 20 months between the first crash in September of 1943 and the last in May of 1945, with many killed within site of the runway, according to a report in Martha’s Vineyard Magazine.

“Oh, he came roaring down,” recalled Hector Asselin of Vineyard Haven, an aerial gunner specialist at the base who saw a lieutenant crash just after the base was shut down at the end of the war. “It was right at dinner time. I was in the mess hall.

“I ran out, and I could see through the window, the thing coming down. The siren went off, and they say there were parts everywhere. Horrible thing. That got everybody, the pilots, the ground crews — everybody. It stirs me a little bit when I think of it now.”

Mr. Asselin also remembered an incident when three men got caught in an unventilated gasoline tank during an inspection.

“They were all young fellows, very little experience,” he said. “It happened so fast.”

Two men were killed in the accident, he said, and their bodies were first taken to the airfield pharmacy.

“They had these two fellows laid right out on the floor,” he said. “Purple. They were purple.”

Outside the base, wartime life had become a matter of routine — blackouts and air raid drills, at least during the first half of the conflict — to the point where many Islanders resented the intrusion on their night’s rest.

“The authorities, both Civilian Defense and Army, have operated on the assumption that the cry of ‘Wolf! Wolf!’ can be sounded indefinitely, and that the people will always appear running and filled with enthusiasm,” said one resident in a 1943 newspaper account.

In less than 200 years, the Vineyard evolved from a place too remote for the government to protect to a key tactical location for training and surveillance.

While Islanders in World War II supported the war effort with the same enthusiasm as the rest of the country, the heavy military presence made many people feel as much on the front line of defense as the colonists in Grey’s Raid. By 1945 Vineyarders were no longer afraid that they would be overrun by the enemy, but they couldn’t yet quite measure how the invasion and long occupation by their own military would change things. Hundreds of young men had been introduced to the charms of Martha’s Vineyard and were coming home to tell their wives and fiancees about it. The war was ending. Two graceful old Island steamers — the New Bedford and Naushon — had gone to Europe and seen service at Normandy as hospital ships. Now there was talk of a need to build a ferry to handle the postwar automobile traffic.

And suddenly, where for thousands of years there had been only scrub oak and the heath hen, there was now an airport.

Comments