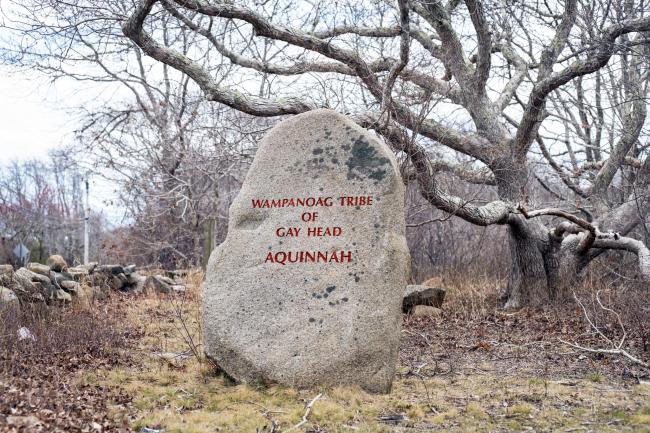

An action at law to evict the town of Gay Head from 238 acres of lands within the metes - the cranberry bogs, the Herring Creek and its banks, and the colored cliffs that give the place its name - has been filed in United States District Court at Boston by the Wampanoag Tribal Council of Gay Head.

“It is our last hope ever to be able to think the Indians of Gay Head can have a piece of the land that they can call their own,” said Mrs. Beatrice V. Gentry, president of the council.

The so-called common lands claimed in papers filed by the council’s attorney by mail Friday from his office in Calais, Me., were parts of the Gay Head Reservation until 1870. In legislation enacted then the General Court of Massachusetts changed the Indian reservation into the incorporated town of Gay Head and, the complaint alleges, “gave all of the tribe’s property to the newly created town.”

In a prepared statement the tribal council said:

“The transfer, according to Mrs. Gentry, amounted to wholesale theft of the tribe’s land, for, as non-Indians moved to Gay Head, the tribe slowly lost control of its asset. ‘Since the Vineyard became a fashionable summer resort, we Indians no longer control our land,’ Mrs. Gentry said. ‘The summer people think that they should be able to use our land as their playground. We think that non-Indians have taken enough Indian land.’”

She said in a telephone conversation that Indians now own less than one quarter of the land in the little town at the western tip of the Island (6.34 square miles, summer population peak 600-700, year round population counted at 118 in the 1970 census, estimated now at 150-200, and Mrs. Gentry added:

“Land in Gay Head is selling at $30,000 an acre. How can Gay Head people afford to buy it?”

It was pointed out that the Indian common lands are exempted from the jurisdiction of the new Martha’s Vineyard Commission by the act creating the agency, and she was asked whether transfer of ownership from the town to the tribe would entail a change in use of the land surface.

“Change?” Mrs. Gentry said. “I can tell you that we have owned that land since pre-Columbian times and have never touched it. The cranberry lands are virgin territory. Nothing has been built on them except a limited-access highway that the state built. We have always maintained those lands and taken care of them. The idea is that those lands belong to us, not to the town. We are going to see that our descendants have a little bit of their legacy.”

The council’s claim, said its attorney, Thomas Tureen of Calais, is based on a 184-year-old federal statute called the Indian Nonintercourse Act of 1790. Its prepared statement said:

“That provision renders void any transaction involving Indian land which is not consented to by the federal government. The 1870 Massachusetts transfer was not federally approved.”

In a related action this week, the Vineyard Conservation Society said in a statement by its director, Robert Woodruff, that it is “anxious to cooperate with all interested groups and individuals to assure that Menemsha Neck (where the cranberry lands are located) remains in its entirety the unspoiled area that it is today.”

If the cranberry lands were given to the town illegally in 1870, they should be returned to Indian status, the society said, adding:

“Regardless of whether the town or the tribal council owns the cranberry lands, we are confident that Gay Head people are aware of the area’s fragile ecology and will seek to preserve it.”

The society and its “immediate and long-standing concern” has to do not with the 200 acres of cranberry lands specified in the suit “but rather with the 38 privately owned acres adjoining the cranberry lands.”

“It is this privately owned land that the Conservation Society and the Gay Head Conservation Commission have been trying to preserve,” the statement concluded.

Mrs. Gentry said the acres under private ownership are not involved in the suit, which claims as belonging to the Indians (in the language of ancient documents) the cranberry lands given to the town 104 years ago, the face of the clay cliffs, and the Herring Creek plus land extending one rod (16 1/2 feet) from the water on each side.

The council’s attorney, Mr. Tureen, is employed by the Native American Rights Fund, the nation’s largest Indian-interest law firm, and is the director of the Indian legal services unit of Pine Tree Legal Assistance, an agency dealing with the legal problems of Indians in the eastern United States.

Comments