The striped bass, valued not only as a premier game fish but also as a commercial catch, is the subject of a three year, multi-million-dollar study by several federal agencies because of its apparently dwindling population.

The study is called a major undertaking by the officials of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Marine Fisheries Service — the agencies directing a broad reaching survey of the striped bass. Experiments in the laboratory will seek to quantify the effects of certain chemical pollutants on bass at each stage in their lives, while field surveys will follow the bass life cycle from the egg stage in fresh water to the trophy-sized adult prized by ocean shore fishermen.

Because new regulations might be urged after the study’s completion to protect the bass from pollution or overfishing, the three year program could ultimately lead to major changes in the traditional habits of Massachusetts sport fishermen.

The government has budgeted $1 million for the study this year, $1.75 million for fiscal 1981, and $2 million for fiscal 1982.

The most recent decline in the population of striped bass began drawing attention in 1974, and according to the government’s figures, reached a 21-year low in 1978. A study of the abundance of small bass and year-old bass done in Maryland also indicated a trend of decline in the numbers of young bass. There has been no strong crop of bass in any year class since 1970.

A year class refers to the young produced in each year’s spawning. When a certain year’s crop of young is unusually large, it is referred to as a dominant year class.

Island fishermen whose memories extend to the late forties or early fifties can recall times when striped bass were scarcer than the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) fear they are becoming now. Historically, the striper catch has run cycles from good to bad, they say, asking why a government study is being funded now.

“As a matter of fact bass have historically exhibited peaks and valleys, and they’re not necessarily correlated with the number of spawning adults. We don’t know why this happens,” Ken Beal of the National Marine Fisheries Service said this week.

“I have a sneaky suspicion congress is saying to us, ‘if you know so much about fish, let’s see what you can come up with.’ “

Mr. Beal said the federal study is a major undertaking for the Fish and Wildlife Service and the NMFS because it will attempt to provide a picture of the striped bass population for the entire area of the coast between North Carolina and Maine — the striped bass’s principal East Coast range.

“We’re looking at a lot of different factors: pollution, shortages in the food supply, and the accumulation of contaminants in fish,” Mr. Beal said.

The issue of contaminants is a key one for the study, because the perception among scientists and fishermen is that the dumping of industrial wastes and toxic chemicals into the East Coast’s large rivers — the Delaware, the Hudson, the Potomac, and the other rivers feeding Chesapeake Bay — is poisoning larval bass and bass eggs in the spawning grounds.

“Ninety per cent of the striped bass in the East Coast originate from the Chesapeake Bay. All the other rivers together only add about 10 per cent. So if the problem is the spawning area, we may be able to get a quick answer to the problem,” said David Allen, a scientist with the regional office of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

But he added: “It’s like finding a needle in a haystack. The best thing would be if there is a single contaminant that was found to be a culprit. Then we could focus on that.

“In lieu of that, the study could generate a lot of good information that will just raise 1,000 more questions. There may not be one common denominator in the decline.”

Chemical pollution has been found in preliminary studies to weaken the bone structures of striped bass, and the three year study will include extensive investigations of the effects of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB’s) pesticides, heavy metals, and industrial chemical wastes on larval and adult fish.

But if a chemical culprit does not present itself, Mr. Allen and Mr. Beal said, suspicion might turn to overfishing, which in turn raises the politically sensitive question of controls on saltwater sportfishing.

In 1978, government figures show, about 4 million tons of striped bass were landed by commercial fishermen along the Atlantic coast. But figures for the large numbers of bass taken by sport-fishermen are almost non-existent, Mr. Allen said.

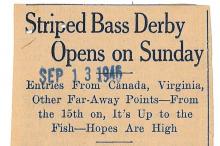

On the Vineyard, the chamber of commerce has records from its annual Bass and Bluefish Derby that indicate what one month of fishing in the fall by about 1,000 anglers can do.

In 1974, when fishermen entered in the derby brought in every fish they caught during the derby to get a certificate, 1,032 bass were recorded. In 1969, 1,236 bass were landed during derby time.

After 1975, Laura Weigle, the chamber’s acting director, said fishermen stopped bringing in every bass, and instead entered only their largest catches. In 1977, under that system, 535 bass were entered in the derby; 508 were entered in 1978. Miss Weigle said it is fair to assume that many more bass were caught and simply taken off to fish markets or freezers rather than derby scales.

The mitigating circumstances of the derby catch records serve to further illustrate the great impact of sport-fishing. Most bass fishermen on the Island feel more fish are caught after the derby ends around October 15 each year. Bass fishing, from boat and shore, is a popular recreational activity up and down the East Coast from spring to fall. The Vineyard derby catch would thus represent only a small portion of the total sport catch each season.

Sportfishing might also be contributing to the bass population decline because the largest bass are also the reproductively active adults, Mr. Allen of the Fish and Wildlife Service said.

“In Maryland and Virginia they actually prohibit the taking of fish over 30 inches in length because they are the reproducing fish,” he said.

To fishermen on the Vineyard, a bass of 30 inches is considered small, and derby competitors aim deliberately to land the largest bass they can.

“A salt water license and size regulations are being looked at,” Mr. Allen said. “But you get into a concern with another license fee, particularly when people feel it is their God-given right to fish from the shore.”

Licensing would be a way to get control of the numbers of saltwater fishermen, and possibly the amount of fish they catch. License fees could also go to fund now poverty stricken saltwater fish management programs, Mr. Allen said.

“Still, it’s going to be pretty hard to swallow, paying to go fish in the surf.”

The completed striped bass study will serve as a guide in the creation of a government response to striped bass management, a response that could have broader reaching effects than just the preservation of the bass themselves.

If chemical pollution in the spawning rivers and bays is the culprit, the federal Environmental Protection Agency may be asked to stanch the flow if chemical pollutants into the rivers. If the study report recommends saltwater sportfishing licenses, the whole character of saltwater fishing, and the presently low level of government interest in either regulating or promoting saltwater game fishing may change.

“No one seems to agree on what ought to be done,” Mr. Allen said. “If you got 50 experts in the room, you’d get 50 different answers.”

Comments