For the Vineyard Gazette, the change to a new production computer system this spring has been as profound as the transition, two decades ago, from hot metal type to offset printing.

This morning’s edition of the Gazette is just the fifth Friday paper to be created on an entirely new production system — a network of Macintosh computers running the latest generation of what is popularly known as desktop publishing software.

The change is generational, rather than merely evolutionary, in several senses. But to frame the transition, some history is in order.

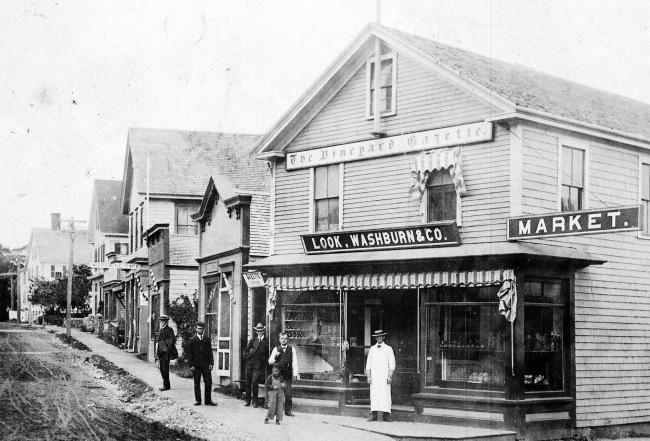

For its first century and more — that is, until the shift to offset printing in 1975 — the Vineyard Gazette was printed using actual type carved from wood and cast from metal, arranged in frames and then inked and pressed against sheets of newsprint. The shift to printing by offset presses meant the end of Linotype machines with their slugs of hot lead and the old wooden California type cases with their tiny compartments of letters.

Ever since its first offset edition ran on the Goss Community presses in May of 1975, type has been a photographic object at the Vineyard Gazette. But from 1975 to 1982 the reporters still wrote their news in the old-fashioned way, on the Gazette’s trusty fleet of Royal typewriters. Two typists copied every story onto paper punch-tape for reading by the machines that printed the stories on photographic paper. These strips of paper, called galleys, were then backed with wax and pasted together on large sheets to make each page of the Vineyard Gazette.

On the week after Easter in 1982, the Gazette made its first real transition into the computer age, installing an editorial, advertising and classified production system made by the Florida-based Harris Corporation. But still the typewriters remained at many desks, for there simply wasn’t room for as many writing stations as the Gazette had reporters. That situation improved in the spring of 1984, when the Gazette completed its second-floor newsroom, an addition built above the press and production areas along Davis Lane in Edgartown.

Of that first computer system, a network based around just two floppy disk drives with a total storage capacity of two megabytes, the Gazette wrote in 1982: “It’s a powerful system, in some ways a system only as good as its operators, and we still have a lot to learn. The office echoes with new words which grate against the soft contours of the circa 1760 walls — words like downloading, default files, format control codes, floppy disks and even a new and horrifying verb: keyboarding.”

The Gazette took less note of its next computer transition, in 1986: That spring the newspaper installed its second Harris system, with a dozen terminals scattered around the building, all talking to a central computer called an 8300 unit. With that transition, the paper’s data storage capacity grew from two megabytes to 50, and its new photographic printers could produce 300 lines of type a minute instead of 50.

But in terms of the weekly work of newspaper publishing, the 1986 Harris system changed the Gazette’s production speed more than its actual methods. The new Macintosh network installed this March has transformed the process itself, moving whole stages of newspaper work from the back-lit light banks of the production room and onto the glowing screens of computer workstations.

Each page of this newspaper is stored in the Gazette computer network’s memory, not as letters of the alphabet, but as a grid of pixels, either black or white, packed almost 1.5 million to each square inch. To accomplish this, prodigious memory capacity and computing speed are required, but these are commodities available in abundance from the computer industry today. The new system’s memory has expanded by a factor of 30, to 1.5 gigabytes, and even the reporters’ writing terminals have more computing power than the mainframe at the center of the previous system.

The Gazette’s news stories are written by the reporters and read by the editors in much the same way as they have been for the past dozen years, but from that point forward the production process has changed almost completely. Now instead of printing out each story as a galley of paper type, the news is edited and organized in computer files according to where it will be published in the paper — from the marine news page to the calendar, from the social news columns to the front page. Finally, using a powerful graphics program called QuarkXPress, pages are built entirely inside the computer and then are output in completed form on high-resolution laser printers built by the Laser‑Master Corporation of Eden Prairie, Minn.

The odor of chemistry is gone now from the Gazette backshop, because the pages of the newspaper are being produced on plain paper rather than on photographic film run through a wet processor. In addition to improving production speed, this new technology is far less noxious from an environmental standpoint.

The Gazette’s new printers, because they think entirely in terms of pages as graphic objects, make no distinction between words and illustrations. Now the advertising work of the Gazette is being handled almost entirely inside the computers for the first time; logos, drawings and photographs can be scanned into memory and handled in the computer, eliminating the need for much work previously done in the Gazette darkroom. One of the two light banks used for pasting up the newspaper has been removed from the Gazette back shop; in its place are tables with computer workstations, a digital scanner and a laser typesetting unit. The second light bank will remain, for use in opaquing the large negatives which in turn make printing plates for the Goss presses.

The Vineyard Gazette’s new production system was designed and installed by the Baseview Products Company, based in Ann Arbor, Mich. Base-view provided software systems for news writing, editing and file management, and for classified advertising production and billing. Baseview is also a Macintosh dealer, and the firm designed and installed the newspaper’s new Macintosh network.

The new systems installed this spring will be used not only in production of the Vineyard Gazette, but also for the newspaper’s sister publications, Martha’s Vineyard Magazine and the Best Read Guide.

The Gazette’s new system is hardly unique, but rather represents the direction taken in the past few years by the newspaper industry as a whole. And as things turned out, what looked at first like a departure from a happy 12- year relationship with the Harris Corporation wound up as nothing of the sort. Late in March, Harris announced that it was so impressed with Baseview Products, it purchased the company.

Comments