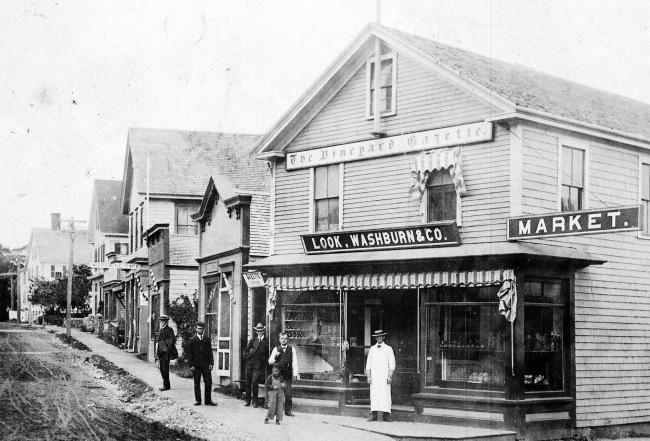

The great storm had wheeled off into the Canadian Maritimes about 45 hours before, leaving a jungle of limbs and power lines almost two stories high on the corner of South Summer street and Davis Lane, just outside the Vineyard Gazette office in Edgartown. The publishers and a clutch of writers and editors had flown to Nantucket to compose and print the storm edition in two slim sections, much of it devoted to how the first hurricane in 37 years had looked and sounded and even smelled, and to an early town-by-town accounting of the damage done. The staff returned to the Vineyard with a paper bearing an unprecedented Wednesday dateline.

By Thursday morning every single copy had been sold, including those meant for subscribers, and the edition had to be reprinted - 16,000 copies gone in one afternoon, one evening and the morning of the next day.

Some of this may be put down to souvenir hunting. The paper carried an unusual banner headline, Hurricane Bob Bashes the Island, and the large gray photograph of the fishing boats straining at their lines in Menemsha was particularly dramatic - but looking back on it now it is also plain to see that Vineyarders and visitors alike actually needed a newspaper by Wednesday afternoon, needed to read about the thing they themselves had just lived through.

By midweek they could have toured most of the Island without much difficulty and seen it all for themselves; radio was giving the Vineyard late information about cancellations, power restoration and relief. But what Islanders wanted was a physical record of what had happened to them on August 19, 1991. Something that explained, for all time, what had befallen their harbors and their homes. Something that might be held in the hands, taken home and shown to friends and family, or opened one day for grandchildren to trace with fingers and be read to.

The Vineyard needed to experience the storm again, this time chapter and verse. It was part of the recovery, part of what made the gauzy dream of Monday afternoon real once more in the sweet-smelling week of heat and chainsaws that followed.

This is a story about how the Vineyard Gazette came to occupy that central place in the life of Martha’s Vineyard, how it came to be the contemporary and essential record of that storm, and of more ordinary aspects of life on the Island. It cannot be the definitive story, because a close reading of hundreds of Gazettes reaching back 150 years to the first issue of May 14, 1846, shows that each publisher, each story, each debate, each editorial view and even each paper has its strength and its measurable weaknesses.

But what’s remarkably consistent through the ages is the clarity of the mission of the Vineyard Gazette - to record in detail all manner of life on this small Island in the North Atlantic. Anyone awed by how the sea has set everything here apart from everywhere else will call that mission self-evident. But an Island newspaper can record the differences of Island life brilliantly and it can fail to do so dismally.

That is what this history of the newspaper seeks to examine - and in part to judge - epoch by epoch, editor by editor: How did it come to be that vital record of Island life? Why did people rush out to buy this newspaper after everything had come clattering down? What was so important about a Gazette that arrived one day late?

Vineyard in 1846 Prospered at Height of Whaling Era

The Vineyard Gazette was born the year a steamboat, the Naushon, first began sailing regularly between the Vineyard and the mainland; the year the Methodists returned to the forests and pastures of outermost Edgartown, where Oak Bluffs would rise up 20 years later, after taking their annual summer retreat of prayer and song to the mainland for one season. It was the year the Mexican-American War began.

It was also the greatest single year the whaling industry of New England ever knew, and more whaling ships were registered in Edgartown and Holmes Hole (Vineyard Haven) than anywhere else. Islanders would never again make as much money over a longer period of time in one business than the men who owned or captained whaling ships.

In the two decades following the creation of the Gazette, 111 whaling voyages would commence from Martha's Vineyard (13 were at sea that very year, 1846, carrying with them $500,000 in Vineyard capital, a tremendous investment for three small coastal villages). Edgartown, where clapboard mansions were rising up on the dirt roads running along the waterfront, also served as a port for Nantucket whaling ships returning home too burdened with oil to cross the sandbar at the entrance to their own harbor. And Vineyard men - especially Chilmarkers and Chappaquiddickers - were in demand as masters of ships not only at Nantucket, but also at the cities of New Bedford and Newport.

The area we know as Oak Bluffs was called Farm Neck; there were perhaps 30 people living in a few scattered farmhouses on hard ground that rolled gently until it ended sharply at a scarp or bluff overlooking Nantucket Sound. There were no cottages yet, no steamboat wharf, no road along the beach, nothing more than pathways in or out, no hint of the village that would rise up almost in an instant after the Civil War.

The main settlement in that area was Eastville, on the shore just across from the growing hamlet of Holmes Hole. Eastville had a tavern, two rudely built churches and a school. It might have become the center of the future Oak Bluffs: The first Methodists from Edgartown had sailed around East Chop and landed there in 1835, but they wanted wilderness in which to stage their rapturous revival meetings and drove inland. Those who came later from the mainland to witness the fervid whooping in the woods would help make what the Methodists called their Wesleyan Grove the center of this newest, nascent town Ñ and the birthplace of Island resorthood.

The roads in Holmes Hole were little better than walks, the village divided into three enclaves: the heart of the town, a “down-neck” section and the forest of West Chop. There were 1,074 inhabitants, mostly fishermen and farmers. There was a new Methodist church at Lambert's Cove, and a saltworks. The trip overland from Edgartown took an hour and a half, the road wandering through a vast, pan-Island, waist-high prairie of scrub oak and grassland - “the sandiest, the most inconvenient, the most crooked, in fact the worst road of the same length on the Island,” wrote Edgar Marchant, the founding editor of the Gazette.

Tisbury encompassed North Tisbury and West Tisbury, villages of farms and mills and craftsmen. Dr. Daniel Fisher, the Island candleworks magnate, kept a grist mill on the banks of Fisher's pond and the trail he rode between this outpost and his main holdings at Edgartown became Dr. Fisher's Road, now an ancient way. A few Indian wigwams still stood at Christiantown.

Chilmark included Gay Head, Noman's Land and the Elizabeth Islands. North Road was not yet built. Menemsha lay on a shallow creek whose mouth shifted with the sand at the entrance to Vineyard Sound. Nothing larger than the smallest dory could manage it. Fishermen lived further to the west, at Lobsterville, which sat smack on the face of the Sound without harbor or shelter of any sort. Each evening these fishermen put the bows of their big-boned, open, double-ended NomanÕs Land boats on wooden rails and hauled them up onto the beach with oxen. Menemsha would not establish itself as a seaport until after the creek was dredged and straightened in 1903.

Already three of the four tribes on the Vineyard were gone - the Chappaquiddicks, the Nunnepogs of Edgartown and the Takemmys of the central section, all lost long before to disease. Only the Aquinnahs survived on a reservation at Gay Head, 200 of them clinging to the common lands, cobbling together old customs and the new religion, running their own affairs though still wards of the state. So shunned by whites were they that although blacks had long been counted in the federal census, Indians were not through the 1850 census. A “frugal, industrious, temperate and normal people,” said the state inspectors in one of their infrequent reports to Boston.

Selectmen in Edgartown were paid $20 per year. Men’s pants were selling at $1 to $2, a fine custom overcoat from $10 to $12. For 10 years prior to 1847, the average yearly yield of the Mattakesett herring creek was 1,270 barrels, or some 700,000 herring, the revenue roughly $5,000 in an era when school teachers were paid $12 a month and a house could be rented for $100 a year. In 1852 the annual expenditures for the County of Dukes County were $3,016.

Resorthood - even the concept of vacationing - was simply undreamed of.

But on Oct. 7, 1847, under a surprisingly black headline, and in his first editorial campaign in behalf of a strictly Island cause - besides temperance - Edgar Marchant proposed in his newspaper of 17 months the idea of The Vineyard as a Watering-Place in the Summer Season.

On the way to South Beach, he wrote, “you pass over a beautiful prairie, if I may be allowed the expression, interspersed with pleasant cottages and large droves of sheep basking in the sunshine, lining the roads for miles.” Fishermen would find “something besides black-fish or tautog; from the blue-fish, perch and striped bass, to the bonito and sword-fish, with numerous other kinds, sufficient to give the most athletic, or dyspeptic personage an appetite for breakfast, should he start at the proper time, prepared for the business.” And “to those invalids fond of easy riding, with pleasant scenery, our Island offers particular inducements; the many farm houses situated in the country, and small towns on the Island, with roads leading thence, through a pleasant forest and rural groves, are seldom to be found at the usual watering places.”

The founding publisher was a visionary.

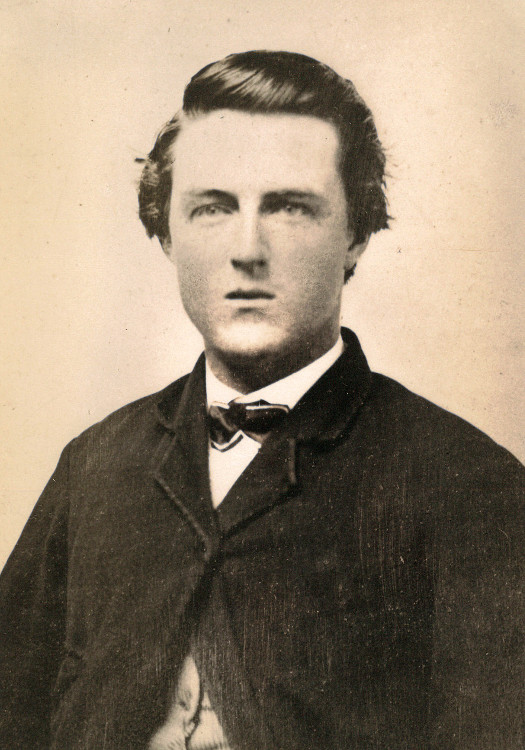

Edgar Marchant

May 14, 1846 - April 17, 1863

He was also strung tighter than piano wire, nervous, outrageous, forever trying to force together into common cause men born with an almost medieval sense of individuality. “A man of positive convictions, he waited not first to learn what others thought, before uttering his own opinions,” wrote Richard L. Pease in a carefully worded resolution for the Edgartown Lyceum at his death, “but with his characteristic zeal and indomitable energy, he addressed himself to the task of impressing his own ideas upon the minds of the community. We shall miss his presence, his earnest, zealous utterances; but his influence will long remain, and his name will not soon be forgotten.”

We may imagine him hurrying down Main street, Edgartown, a small man with thick, trailing whiskers, the folds of his cape snapping in the breeze, always on a mission of municipal or moral improvement. Listening impatiently to adversaries at town meeting, pushing his beaver hat in and out, stifling the urge to erupt, usually failing. Willfulness ran in the family:

He and his son George Duncan - a printer in the Gazette office, born the day it was founded - quarreled constantly. The boy grew up to be a rather wayward young man and one afternoon, inebriated, he accidentally drove Gen. Ambrose Everett Burnside - commander of the brigade that had opened the first battle of Bull Run and the general who lost Fredericksburg in 1862 - into a muddy creek on a trip from Edgartown to Oak Bluffs. George Duncan returned late and unapologetic to the stable. There the father, first worried, then humiliated and raging, dove at the son and the two wrestled to the ground. “Surrender, George Duncan, surrender!” cried Mr. Marchant. “Never, father,” shouted the young man, “as long as I’m on top!”

We know only a little more about the founding editor. Born on the Vineyard, the ninth of 12 children, he learned the printing trade under a brother, Gamaliel. His first foray into newspapering was probably at the Gloucester Telegraph, and he became an editor of the Boston Traveler. He founded the Vineyard Gazette just after his 32nd birthday. In nine frenetic years after his first term as publisher ended in 1863 he would go on to edit the Woburn Journal, Essex Statesman, Abington Standard, Randolph Register and Woburn Advertiser before returning to the Gazette for a second term as editor and publisher in 1872.

Mr. Marchant knew that the Gazette would be the only newspaper most Vineyarders ever saw.

His trick at first was to concentrate on news of the nation and the world, about which his readers would know little, and steer clear of Island news beyond Edgartown, about which his readers would probably know much more than he. His first editions carry stories he picked up from mainland papers of the conquest of Vera Cruz and the Castle of San Juan de Ulloa, of the latest tariff bill to pass both houses of Congress, of a sharp increase in the number of people dying in Boston of cholera, probably due to the warmth of the weather and “the large quantity of unripe and stale fruit which is daily consumed. There were six deaths in Cross street on Thursday night, of cholera morbus, three of which were in one house, a mother and her two children.”

On the subject of the Vineyard, he campaigned more than he chronicled, calling for a Dukes County Agricultural Society, bigger steamboats, better mail service, authentic hotels, more and better roads, a railway and the vanquishing of “King Cider.” It was the only forum by which Vineyarders could debate matters of increasing economic importance to the whole population, and one man, this editor, set the agenda and defined the terms. Even those who suffered his idea that businesses should work together to promote the Island, and even worse, that town government ought to help, had to answer his calls in his newspaper. The Gazette forced a conversation among a people who weren’t much for talking. It began to unify a place that deeply mistrusted the word.

“We shall furnish the latest news, both foreign and domestic, and in our selections we shall endeavor to unite the agreeable with the useful,” he wrote in his introductory message. It would have been both agreeable and useful if Mr. Marchant had furnished posterity with the latest news of the laying of the first telegraph cable to the mainland in 1855, perhaps, or the installation of the glittering Fresnel lens at the Gay Head Light in 1856. But as editor of a distinctly Edgartown paper, forward-looking, liberal, easily distracted, seeking to prove to the town the relevance and leadership of his journal every week, he was more booster than annalist. Besides, it was hard to get out to Gay Head. The roads were too bad.

For all his imperiousness, better steamboats, better roads and eventually even a railroad did come to the Vineyard. So too came a gradual rise in prosperity even as whaling began to shoal. In the fall of 1861 Mr. Marchant the Democrat was sent to the state House of Representatives by a sea of Republicans. The Vineyard had grown to admire, if not love, this excitable man and to respect what he had created from nothing. He served two years without breaking his association with the paper, but on April 24, 1863, he sold it to James M. Cooms Jr., whom he knew to be a man of “good education, an excellent printer, and an energetic, discreet and honorable citizen, one to whom I commit the future of the Gazette with a full assurance that its fair name and fame will never be tarnished nor its usefulness abridged.”

James M. Cooms Jr.

April 24, 1863 - July 19, 1867

He was both nephew and apprentice to Edgar Marchant, only 23 - we believe - when he took command as editor and publisher. It was a slim sheet of four pages the founding editor either sold or gave to Mr. Cooms, a papyrus of oatmeal gray - no headlines, no lithographs to accompany the news, nothing to break up the fuzzy racks of type. The front page carried essays and random notes, preset boilerplate sold to the paper by mainland compositors. Advertisements and a few marine notes appeared on Page Three, with more ads and poetry on Page Four. News of town - meaning almost always Edgartown and Edgartown alone - county, state, nation and world was published on Page Two. Mr. Cooms changed none of this very much.

His was a capable editorship marked by instances of splendid achievement. The paper of April 21, 1865, carrying the latest news of the murder of Abraham Lincoln and the flight of the assassin is the first truly urgent and enthralling edition of the Gazette ever published. He printed war news faithfully and must have run every letter handed to him by the parents of Island boys in the field. We yet find no regular reporting from any village but Edgartown, but there is a slight pulling in of focus, fewer prefabricated stories about French and Russian emperors, more about the doings of New Bedford. The type begins to vary here and there; it is larger and substantially cleaner. He really was “an excellent printer.”

His legacy to historians is the attention he paid to the Camp Ground as the tents gave way to cottages, the religious meetings to resorthood. “The moon pours her light upon the forest and upon the sea,” he wrote after a midnight stroll around the tented field in 1864, the last of the pastoral days. “We go to rest, but as we turn towards our own tent, we look on the many around ours. Far from the city, out of the workshops, the warerooms, away from domestic cares, have come these sojourners in the wilderness to rest awhile; to renew old friendships, to form new ones; to speak to one another on high themes.”

Two years later he wrote:

“The prospect is great of an unusual gathering at Wesleyan Grove this year; such an assembling as has never crowded these extensive grounds. The character of this immense body of sojourners cannot be expected to be distinctly religious, for the religious element is becoming subsidiary to the gratification of the desire for pleasure and comfort.

“The purpose that led those pioneers of Methodism to seek this exclusive spot was truly commendable, but the accomplishment of their purpose opened to the knowledge of the world the advantages of comfort and pleasure to be obtained in a brief sojourn amid these ‘grand old oaks,’ and now so extensive has this knowledge become, and so general the appreciation of the grounds and its surroundings, that from a brief sojourn it is found to be worthy to rival either of the fashionable summer resorts along our coast; and from ‘a canvas city of the woods’ it is fast growing up as a substantial town, closely populated, and within whose regular and well-populated precincts may be found a truly social people enjoying the healthful influences of cool breezes amid a quietude and retirement that is refreshing to tired nature.”

But just as the wave was about to break, this young editor gave up his pen to another young editor, an exuberant and talented fellow who liked to call himself Charlie Mac.

Charles Macreading Vincent

July 26, 1867 - September 27, 1872

He was just the lad to lead a paper through the gaudy, gorgeous postwar boom.

Charles Macreading Vincent, another Edgartown boy once apprenticed to the founding editor, threw back his head and crowed over the lacy and ornamental developments hammering themselves together at Oak Bluffs, which would soon boast to the world that it had become the “Cottage City of America.” “Who comes next in the line of new enterprises?” he asked. “Welcome all! And may the tide continue to rise until the whole of Martha’s Vineyard shall be filled with life and activity.” Just 24 and a veteran when he took over the Gazette July 26, 1867, his letters home from the war - now on file at the Vineyard Museum in Edgartown - had hinted at a keen and playful mind. But it took the editorship of the Gazette in a time of thundering prosperity to root out his joy in journalism.

It was a rapturous hour. It thrilled and inspired him, sometimes to the point of cheekiness.

“It is useless to waste adjectives in vainly attempting to portray the enormity of the squashes, the stupendity of the pumpkins, and the giganticity and general outrageousness of the turnips and beets,” he wrote after covering the agricultural fair in West Tisbury for a slightly exasperating third year in a row. “Outside the hall the attractions are considerably less than in previous years. The vendors of gingerbread, gold watches, and whips muster as strong as usual; but where is the fattish woman and the attenuated man, the swallower of swords and the masticator of smallish stones? Gone are they one and all and their glory forever departed. At any rate they ain’t here.”

He was the first editor to range out across the landscape to look for news on a systematic basis. On May 27, 1870, he launched a column called Local Jottings, our first weekly record of the travels of individuals, trends in the weather, arrival of bluefish and meetings of the agricultural society - though he wrote nothing about the incorporation of the town of Gay Head that spring, a rare lapse. He offered new departments to display advertisers, including a Traveler’s Guide, Edgartown Business Cards, New Bedford Business Cards and New Advertisements. Two-column ads began to break the monotony of the old linear bills. Type size grew. The rigid gothic masthead busted open into an expansive banner of plain Roman type, upper and lower case. The value of the paper doubled.

Fifty new cottages were built at Oak Bluffs in 1869. Forty more in 1870. That year the last of the great oaks shading the preachers at Wesleyan Grove was cut down. “The ruthless hand of time,” wrote Mr. Vincent on June 17, “has rendered desolate the pride and joy of the Fathers who first worshipped in this beautiful grove of the thrifty and vigorous oaks. Alas! How are the mighty fallen! It is with a feeling of sadness we witness the departure of the venerable oaks within the circle by the preachers’ stand. . . . These old oaks have stood the storms of years, and their friendly shelter has often been sought, but now they are numbered with the things that were.”

He was the most devoted reporter the Gazette had yet had. The liveliest writer, too. He perceived that Edgartown - bereft of whaling by 1871, the money of the captains now flowing north to Oak Bluffs and south to the newest development at Katama - was in serious trouble. “The Camp Ground and Oak Bluffs appear to have sapped what little vitality it once had!” Mr. Vincent wrote. “And as she lies beside her beautiful, peaceful harbor, almost lifeless, we catch the reflection of her inscription from her mirrored waters, ‘Died For the Want of Nourishing Enterprise.’”

Charlie Mac did not stay long enough to understand that the satellite village of Oak Bluffs, whirling on a more rapid and exciting axis, was already acquiring its own sense of identity and style. He never heard the resentment over improvements he had endorsed such as the Beach Road, plainly intended — as everyone knew — to draw Cottage City visitors down to the groggy imperial seat of Edgartown, which was doing nothing for itself. Mr. Vincent would scamper off to Boston to edit an amusing column in the Globe called Table Gossip, and die too young of diphtheria in the spring of 1881, just 37 years old and married only two months to his second wife.

Edgar Marchant

October 4, 1872 - October 19, 1877

Charlie Mac didn’t stay long enough to deal with the crash, either.

That unhappy task fell to the founder, Edgar Marchant, who returned Oct. 4, 1872, to a second term at the Gazette. Peripatetic and irrefutable as ever, Mr. Marchant, nearing 60, must have come home with a sense of deep satisfaction, believing he would close out his days presiding editorially over the watering place that had exceeded even his vision of a quarter-century before. Instead he presided over the bust.

“The world is moving as it never has moved before,” he wrote in his new introductory message, “and our own country is manifesting great activity and enterprise in developing her resources and making improvements. The Vineyard has felt the electrical touch of the times, and now steps forth in right royal earnest to win wealth and fame.

“Already the attention of thousands in other parts of the land has been drawn to her as a place of summer resort. The marvelous bounty of our location, the cooling and beautiful breezes of the sea, allure the stranger in the summer months to our seaside home, and new and tasteful buildings erected by them adorn our shores and sea borders. In short, we are rising like a city of the sea to the view of beholders. All we have to do is to continue united, work solidly together, and secure the harvest.”

In the fall of 1873 Jay Cooke, former financial agent for the United States during the Civil War, declared bankruptcy, taking with him $15 million of the paper of the Northern Pacific Railroad and $4 million in government deposits. The great postwar boom shuddered to a halt, depression settled over the land and the long bull market for Cottage City lots simply died away.

Down at Katama the old whaling masters had just finished building a grim-looking Victorian hotel on the barren grasslands. Nobody had money to stay in a hotel or buy lots in the prairie around it. Mr. Marchant decided the remedy was to get people moving around, to shuttle them by shoreline railroad from the successful resort at Oak Bluffs, through the village center of Edgartown and beyond to the lonely Katama outpost of clambakes and surf and blustery winds. All through the winter of 1874 he clanged for the railroad in the pages of the Gazette, finally standing up at town meeting — so much for the disinterested journalistic observer — to insist that the village subscribe $15,000 to the almost unmarketable railroad stock. An unprecedented and egregious wedding of private and municipal interests, his opponents bellowed.

His answer, quintessentially and delightfully Marchant, is famous:

“We want a railroad and we are going to have it,” he quoted himself saying in the Gazette. “Refuse to encourage and lend our aid to this enterprise, and this town will disappear into the darkness of oblivion. All spirit of improvement will depart from our borders, men of brains will go where they can use them, and for aught I can see to the contrary, the town will become a waste, a howling wilderness; rats and mud turtles will crawl over our streets, and owls and bats sit in our high places.” Mr. Marchant won by the awesome majority of one vote.

The Gazette carried the day, but it had lost a town. To Oak Bluffs the railroad was the delirious and unconscionable final effort by Edgartown to siphon away its lifeblood during a time of desperate economic illness. Oak Bluffs began to think about secession, about separating from Edgartown and incorporating itself as the town of Cottage City.

In the first skirmishes over division from the parent town Mr. Marchant - a one-worlder from the first - acted neither the conciliator nor the diplomat. He reprinted a piece in the Boston Herald favoring division, writing after each argument: “This is a lie, pure and simple,” and “Another lie, a supreme, defiant, splendid lie,” and “A lie like the above would reach the dignity of a crime did it emanate from the source of truth.” The anger of Oak Bluffs toward Edgartown and particularly the Gazette would linger into the next century.

The whole Island declined. Prof. Nathaniel S. Shaler, touring the western reaches in 1874, wrote: “One never sees a field newly won from the forest, while on every side are signs of the gain of the woods on the fields.” Many of the farmhouses were deserted. He saw few children. Most of the men were past the prime of life.

“The youth born on this Island have enough of the old Viking blood in them to make them natural wanderers. While they went out for fortune on the sea, they came here to rear their children and leave their bones in their native soil. But the paths of the land do not all lead home again, so the old people are left to live and die alone. The old, old houses, once strong, now worn thin by the beat of the weather, the crazy out-buildings and fences, with two old, weather-worn people, form the sad homes on many of the little farms.”

Mr. Marchant had inherited a modern, lively, essential paper from Charlie Mac Vincent. In the face of financial adversity, he tried to keep it that way. He expanded the social news on the back page, covered ritual events - a thing he almost never did during his first editorship - such as the village obsequies on Memorial Day and meetings of the Dukes County Academy. He regularly reported blurbs about both Vineyard Haven and Oak Bluffs, and gave us our first glimpses of ordinary Vineyarders passing through extraordinary moments of their lives (“The presents were both numerous and tasteful,” wrote an anonymous reporter after the 20th anniversary celebration of Mr. and Mrs. Mayhew Look of West Tisbury, “but I have not time to describe them.”)

His valedictory on Oct. 19, 1877, said that “in looking back over his long career as the editor of this paper, a period covering 22 years, he does not feel that if he could he would erase one line which he has written for its columns.” But near the end of his editorship and his life, he gave a better picture of himself - perhaps the best we have - answering yet another critic on the floor of town meeting:

“Mr. Marchant said that their malice-tipped arrows rebounded from him as from the hide of a rhinoceros, and left him unscathed. Once persuaded of the justice of his position, he should stand by it, and the envenomed shafts of the Devil himself could not drive him therefrom. . . . But I cherish no hard feelings toward any gentleman in this house. Everybody is my fellow citizen, and I love ye all.”

Edgar W. Marchant

October 26, 1877 - June 28, 1878

It is sad to think that Edgar Marchant lived only long enough to fear that all his work might be undone.

He had sold the Gazette to another nephew, Edgar W. Marchant, who ran the paper for just eight months, from October 26, 1877, to June 28, 1878. Almost instantly the Gazette went as gray and stolid as it ever was in the 1840s. Town columns, Island news and even the new florid headlines faded away, replaced by boilerplate from Washington and New York, where Edgar W. had worked the previous 15 years.

We cannot be sure what the problem was. The paper looked crisp, if flat. It was filled with news, if the wrong kind. He never missed an issue, if anyone cared. Country editorship was not for him.

His finest moment was the black-bordered edition commemorating the death of his uncle, the founding editor, on Jan. 13, 1878. The next finest was his last, in which he fled the office with something close to an apology:

“Taking into consideration the benefit that would thereby be conferred upon the patrons of the Vineyard Gazette, we have disposed of the paper to Messrs. Keniston & Jernegan,” he wrote. Will Jernegan soon dropped out, leaving Samuel Keniston to rebuild the Gazette alone. And the successors of the editorship of Edgar W. would have to cope with the emergence of a rival, the Martha’s Vineyard Herald, established in the final weeks of his tenure. Today the Herald is generally considered the better paper through the end of the 19th century. The Gazette would not finish it off until the Houghs purchased the Herald in 1922.

Samuel Keniston

June 28, 1878 - March 16, 1888

“It will be our endeavor to make the Gazette a live paper,” Mr. Keniston promised a demoralized readership, “one that shall be welcome in every home, and wherein everyone shall find something to entertain.” He was the most gifted and amusing writer yet. Reporting August 12, 1881, on an attempt to stage a fox hunt on the waste of Katama, he wrote:

“Meantime it began to be noised about among the people that owing to the intervention of the society with the long name, or from some other cause, the fox had been excused from running, and instead thereof had been decently killed and dragged around the course at the tail of a cart, thus affording the desired ‘scent.’ This announcement cast a temporary gloom over the spirits of the crowd; for, although it might be the way the thing was conducted at Newport and other places, it seemed to the average man a good deal like the play of Hamlet with Hamlet left out.”

Mr. Keniston faced three challenges - restoring balance and civility to the coverage of rebellious Oak Bluffs, at which he sometimes succeeded despite his merry and sardonic style; reintegrating the Gazette into the life of the Vineyard, at which he worked wonders as both the Island and the paper recovered from implosion, and recording a dead march of disasters on both sea and land, which he did both brilliantly and terribly.

It was clear by the time he took his seat that Oak Bluffs was lost. Mr. Keniston would separate what he saw and heard at the secessionist meetings from what he felt about them. He would not write journalistically, as the founder had, that the secretary of one of those meetings had “raved like one fully mad.”

The reason was economic. Furious businessmen in Oak Bluffs in the spring of 1879 had set up a new paper, the Cottage City Star, which looked fine and was doing a handsome business. Reporting that an Oak Bluffs resident loyal to Edgartown “sank into utter insignificance and cowered like a frightened cur” before a multitude of hooting rebels - as Marchant once did - was no way to win back that resident, or the multitude, to Gazette subscription lists.

When Oak Bluffs finally won independence as the town of Cottage City in February 1880 the Star yodeled, and the Gazette sighed and shook its head. For the next 15 years it fired darts whenever the newest town puzzled over the expense of paying for schools and fire departments and, given the old battles between the two villages, especially when it tried to figure out how to build better roads.

On Jan. 25, 1884, Mr. Keniston swept away all his regular news to devote the entire second page to the loss of the passenger steamer City of Columbus, which had run onto the rocks off Gay Head and sunk, killing 103 passengers and crew, the worst disaster in Island history. It was a heroic piece of work by the editor, 100 inches of copy culled from the far end of the Island and set by hand one letter at a time. There is original reporting of the bravery of the Gay Head Indians who were capsized and nearly killed in two rescue boats trying to reach the ship in yowling winter winds, and a series of horrifying vignettes: “[O]ne of the most pathetic incidents of the wreck was the discovery of the dead body of a woman with a pair of baby shoes frozen to her dress just below her belt, within which the little one’s feet had doubtless been confined to be the more securely held within the motherÕs embrace.

It was the Gazette’s finest hour of the 19th century, following by five months one of its worst - the failure to report the fire that destroyed Vineyard Haven. The catastrophe occurred on a summer weekend and Mr. Keniston stuffed all the news into a Monday edition of the Cottage City Chronicle, a seasonal paper he published to compete with the Star in Oak Bluffs. Into the Gazette — the newspaper of record — at the end of that week he reprinted nothing and added only a ledger of who was rebuilding and who was selling. The Chronicle and whatever he wrote about the Vineyard Haven calamity is lost.

Mr. Keniston had set out to make the Gazette a true Island newspaper for the first time, reestablishing columns from Edgartown, Oak Bluffs and Vineyard Haven, soon adding Chilmark and West Tisbury. Even Gay Head and Gosnold cropped up occasionally. He chose swanky type to head the columns, which looked clean, broad and sharp. By the summer of 1883, rows and rows of social items made up most of Page Two. The letters, the advertising and the ease with which he filled his pages with Island news proved that Mr. Keniston had once again made the Gazette an integral part of Vineyard life.

Charles H. Marchant

March 23, 1888 - May 27, 1920

Mr. Keniston served 10 years. The next editor would devote his life to the paper, serving as a printer and foreman before his own editorship began in 1888 and staying on to assist a pair of youthful new publishers for 10 years after his term ended in 1920.

Charles H. Marchant was a grandnephew of the founder and the son of a whaling master, the demands of whose profession meant that the future editor did not meet his father until he was three. His successors, the Houghs, adored him. After the Old Editor, as Henry Beetle Hough called Mr. Marchant, had been gone from the Gazette a dozen years, “his legacy to us was still bright. Sometimes we could almost accept the illusion that we ourselves remembered the old days of which he had told us, and of which he had written. Croquet, clambakes, and bicycling triumphs; Matty Williams reciting ‘Lasca’ and Marie Burroughs doing the poison scene from Romeo and Juliet in the town hall.”

It is hard, then, to look back on so much of his editorship with disappointment.

The great problem, after a bright start, was one of stagnation. He briefly expanded the Gazette to eight pages, an amazing feat in a barebones shop. He bestowed its modern masthead, introduced the first photography and wrote with grace. But he let the editorial column disappear for a vast stretch of time. Almost to the end of his editorship he stuck to the archaic tradition of running essays and boilerplate on the front page (Ferocious Whales, Torture Machines, The Discovery of Florida) and consigned to Page Two the arson of two grand hotels in Oak Bluffs and even the monstrous Portland Gale of 1898, which drove 21 schooners ashore and killed 10 men in Vineyard Haven harbor alone. He missed stories he himself had thumped for, such as the grand opening of a first class hotel in Edgartown, the Harbor View, and he devoted only a few paragraphs to stories that deserved much more, such as the incorporation of West Tisbury in 1892. He remained depressingly Edgar-centric through most of his 32 years at the desk.

Another paper was doing better.

The Martha’s Vineyard Herald had swallowed up the Cottage City Star in September 1885 and under the leadership of a Baltimore native and former Confederate officer, Charles Strahan - who had championed the separation of Oak Bluffs in the Star and thereby won a rebellion at last - was teaching the Gazette a weekly lesson in community journalism.

Through the mid-1890s - one of the few periods from which enough Heralds still exist to make a direct comparison - the rival paper covered scores of stories, great and small, that the Gazette never mentioned: the first run of the electric railroad to Vineyard Haven; the arrival of a fireman’s band in Oak Bluffs; lawn fetes in Vineyard Haven; a bicycle race of three miles from “the stone crusher on the state highway to Waban Park and return”; the arrest by the Vineyard Grove Company of two photographers who bought tickets to the bathing beach and began to take pictures of the bathers; the retirement and towing away of the old steamer Island Home, veteran of 40 years’ service to the Vineyard and fated to become a coal barge in Boston; whist parties and shellfish suppers.

In short, a journal of Island life, and while the Herald was as much an Oak Bluffs paper as the Gazette was an Edgartown one, through these years it chronicled in depth a much wider array of subjects, both on the Island and on the mainland. Mr. Strahan devoted so much space to the debate over gold versus silver in the election of 1896 that Mr. Marchant suggested he be nominated Secretary of the Treasury if William Jennings (Cross of Gold) Bryan won.

By 1903 Mr. Marchant had improved, forced into it by the competition.

He came to see, as Mr. Hough later explained, that the best stuff in a country newspaper was often the commonplace, the typical, the event that recurred month after month or year after year. What he did not see, or at least record, even toward the end of his editorship in 1920, was that the world he had known — a world, as the Gazette later said, of “hard-fisted and determined men who saw hardships, battled adversity and winning or losing put up a fight which compels admiration” — was beginning to slip away. There were still clear memories of things the paper had never set down — what it was like to swordfish by catboat, or circle the planet in a whaling ship. How the women of Vineyard Haven did so much to fight the fire in 1883. Why so many hundreds of Island men had risked everything to travel to California to dig gold in 1849.

Mr. Marchant, who had spent almost his whole life on one Island, and virtually all of it in one office, could not see that it was all coming to an end. He did not think to get their stories before it was too late.

“We could see long ago that from one point of view we were participating in the final scene of the drama of a New England community, a community of a New England that had to die under the flood of the modern world,” wrote Mr. Hough in Once More the Thunderer, his second book about the Gazette. The Houghs began their esteemed joint editorship determined to put that final scene down on paper before it was lost.

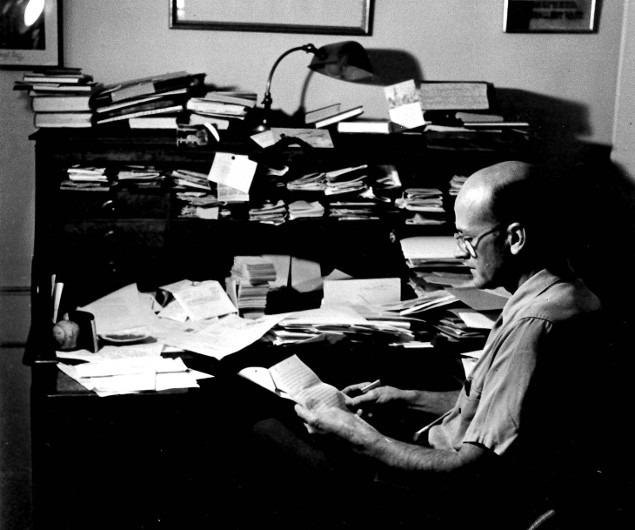

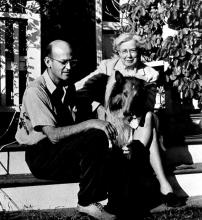

Henry Beetle Hough and

Elizabeth Bowie Hough

June 3, 1920 - April 12, 1968

His first editorial, the week of August 5, 1920, advised sheep farmers to hold on to their wool until prices rose. Among his last were encyclicals on time sharing, McDonald’s and the land bank. When the Houghs took over the paper it had no linotype machine; when his editorship ended it had just installed its third generation of computers. The week they first published the Gazette — June 3, 1920 — four people were needed all morning to manufacture 600 copies on a hand-cranked press. The week he died, in June 1985, one man watched a bank of four offset presses crank out 16,000 Gazettes in little more than one hour.

He was a slender man, stooped in his old age but still clear-eyed and wry, with an encyclopedic knowledge of Island genealogy, history, nature and the old place names where the new houses were going up. The man who wrote editorials about the archaic idioms and pronunciations he was still hearing on the streets of Edgartown when he was 25 dazzled people well into his 80s with his command of a new language forced upon him by the modern era — a language of developers, of planners, of economists and politicians.

She was a white-haired woman who wore rimless spectacles, serving as editor in chief in all but name for almost 25 years after 1940, when he began to write books regularly and concentrate on editorials. “First or last,” he wrote on her death in June 1965, “she did about everything there was to be done on a weekly newspaper, running the linotype, selling ads, writing and editing, scolding and inspiring, driving young reporters to write with taste and clarity, expecting them not to do everything but to do well whatever they had instinct or talent to undertake.”

It would require a full section of this anniversary issue to spell out the significance of the 45-year editorship of Elizabeth Bowie Hough and the 65 years of Henry Beetle Hough. It began with an explosive and celebratory reinvention of the Vineyard Gazette all in the first week, a sweeping away of the crowded old boilerplate and the creation of an airy front page filled with Island news: the five remaining veterans of the Grand Army of the Republic attending the ceremonies of Memorial Day; the saving of Mrs. Ralph Emerson’s cottage from fire at West Chop; the death of Joseph T. Pine, six years old, who collapsed from heart disease when called in from play by his mother. They took a 19th-century paper and in seven days remade it entirely. That June 3, 1920, edition still looks modern today. Henry Hough was 24 years old.

They were the first editors from the mainland, and never lost the mainlander’s sense of wonder at Martha’s Vineyard. Three principles drove them throughout their stewardship: to record history before it was lost and show how tradition played an essential role in contemporary Vineyard life; to define what was extraordinary about a society and a wilderness out in the sea; and to campaign for the preservation of this apartness in all its forms - customs, commerce, wildlife.

Henry Hough was a boyhood summer resident of Indian Hill, born in New Bedford on Nov. 8, 1896, and a graduate of the Columbia School of Journalism where at the age of 22 he was awarded a Pulitzer Prize for an essay on the history of the American press. Betty Hough was raised in Pennsylvania and met her future husband at Columbia. They received the Gazette as a wedding present from his father, George A. Hough, the executive editor of the New Bedford Standard. A brother, George Jr., ran the Falmouth Enterprise.

The revolution begun that first week of June in 1920 lasted 12 years, until the Depression damped down the first wave of freshness and inspiration.

On May 8, 1925, they printed the Gazette’s first known profile of a living Islander - Capt. Isaac Norton, a coaster, fisherman and member of the former United States Life Saving Service, who dwelt happily on his memories of whaleboat racing on a two-mile course off Oak Bluffs 50 years before. They hired Joseph Chase Allen, the Gazette’s first full-time reporter, who sometimes wrote the news in rhyme and for more than 50 years quoted prices and told yarns about Island seafarers on a page called With the Fishermen. They evoked Island life with the smallest brushstrokes, creating a column of incidental quotes and overheard storefront conversation called Cutting Crosslots, another of offhand, ironic events and commentary first called Vineyardana and later Things Insular.

They created the Tuesday paper in 1929, the Invitation and Directory editions during the depths of the Depression to help inaugurate a string of precarious summer seasons and a birder’s column in December 1953 to chart the astonishing migrations that swept over the Island each spring and fall. They introduced columnists Dorothy West and Louise Aldrich Bugbee of Oak Bluffs. The Houghs opened the pages of the Gazette to the beautifully stark lithographs of Sidney N. Riggs and the more expressive cuts of Bill Abbe, and to the first in a parade of photographers — Clara F. Dinsmore and Edith Blake.

They were deeply aware of a growing summer audience.

Four huge steamers, licensed to carry 2,000 passengers each, were built between 1923 and 1929. New houses were going up all across the Vineyard. “One Moment Please!” said an advertisement at the end of the season in 1927. “Before you go, don’t fail to enter a subscription to the Vineyard Gazette. It will follow you and come as a weekly visitor to your winter home with all the news of Martha’s Vineyard. Week in and week out, the newspaper prints column after column of comment and occurrences. Here is Vineyard history in the making, and if you are interested in the Island you cannot afford to be without it.”

They would soar whenever history demanded it, producing grandiose front pages and reams of news that would have challenged the city room of a mainland daily: Joe Allen writing in a garage by the headlight of a car after a hurricane carried away Menemsha; the editors improvising the first banner headline ever for an election extra, inventing lines that wouldn’t use more vowels than the few they owned; and at least one edition, in 1933, that no mainland paper ever would have dreamed of, a paper of bold upper case headlines, a photograph of a grouselike bird bordered in black and four pages devoted to its extinction. The heath hen was a cousin of the greater western prairie chicken. Its last home in the East was the vanishing Vineyard prairie.

Mr. Hough had chronicled the decline of the heath hen closely through the second half of the 1920s, seeing before most men that it was possible for living things to run out of room. Among the first and best examples of his transcendental prose on nature appeared in the paper about the extinction, April 21, 1933. The editorial was called A Bird That Man Could Kill:

“The most prosaic scientist . . . has lain among the black scrub oak in the white mists of a chill April morning and has returned to write poetry. The meticulous observations and Latin terms appear modestly, softened by a cloak of mystery. We read of the birds appearing ‘as if by magic.’ We are told that the call of the heath hen did not rise or fall, but ‘ended in the air like a Scotch ballad.

“. . . And so it is that the extinction of the heath hen has taken away part of the magic of the Vineyard. This is the added loss of the Island. There is a void in the April dawn, there is an expectancy unanswered, there is a tryst not kept. Not until the great plain has grown again a forest of tall pines and cedars, such as that which wooded the level acres a few centuries ago, will the loss of the heath hen be forgotten.”

It was the event that turned the Gazette conservationist. Henry Hough inspired the creation of Sheriff’s Meadow Foundation, the Vineyard Conservation Society and in the spring of 1970 he led the paper with a proposal by Edward Logue of West Tisbury that would take root as the Vineyard Open Land Foundation.

The regulatory hand of government clasped the Vineyard during the New Deal and tightened its grip during the war. The Arcadian world was giving way to a more complicated, political one. “A good many people, especially those at some distance from the Vineyard, may feel puzzled by the rapid sequence of events in the transportation picture,” Mr. Hough wrote of the creation of the Steamship Authority in April 1949. “[L]et no one think that what happened at the State House last week was of minor importance. It was a turning point vital to the future of the Vineyard.” Thus did the Gazette begin to play the role of interpreter and crusader, especially for its mainland audience.

Mr. Hough told his readers what they ought to watch for, what to resist, whom to write. He counted on the summer residents to insist on the preservation of what they had fallen in love with and invested in. He told them that the taxes they paid gave them an important, if indirect, say in town government, that only concerted efforts could forestall the forces that were making the Island too much like the places they had come from. Unity was the important thing. Speaking loudly and unceasingly, with one voice.

He was like the founder in this way.

Increasingly through the 1950s and 1960s the admonitory tone crept into coverage of the news itself. Television Tower Threat Looming Again on Island read a headline Jan. 22, 1960. Arguments for zoning, for planning and for the Islands Trust bill, which in the 1970s would have made the federal government a partner in the defense against rapid and thoughtless change, were read by some as attacks on Island business and progress of any sort. Critics said that the paper was written mostly for summer people, that it failed to report the views of those it disagreed with, that its editorial voice was growing nostalgic and even petulant.

Betty Hough died June 21, 1965. Henry Hough, nearing 70, was now regarded across the country as one of the preeminent American journalists of the century, certainly the most famous country editor. In his lifetime his name became synonymous with Island history, with the natural world, and with the unending campaign to save its character - by which he did not mean appearance, but way of life.

“What has preserved the Island in its natural attractiveness until recently has been the fact that for 300 years it lived in an economy of production,” he wrote near the end of his career. “A service economy, as it is called, has set in like an irresistible tide in the past few decades, culminating in the intensive enterprise of tourism which by its nature exploits rather than preserves, promotes congestion, depends more on turnover than long term advantage, grows through appeals of mass advertising, and in its worst form establishes crudely formed ‘developments’ from which the old rurality of the Island is excluded. Sophistication and conformity set the standard of new times.”

He had long contemplated retirement.

“Apparently there is no way to taper off as there is in some worldly occupations,” he wrote as far back as 1950. Country editorship, he had discovered, “is all or nothing until the end.” He would keep writing editorials for another 20 years, almost to his death on June 6, 1985, but in 1968 he found a new family to run the Vineyard Gazette. Except for the tenures of Charles Macreading Vincent and Samuel Keniston, it would be only the third family to publish the paper.

James Reston and Sally Fulton Reston

April 19, 1968 - July 5, 1988

The relevance and even the survival of the Vineyard Gazette was at stake.

The machinery by which the paper was composed and printed was 40 years old and older. The pace of change had quickened but the Gazette lacked the staff to report how all six towns were meeting the challenges of the day. The paper struggled to define itself in the new era. What sort of country journal could it be when the headlines were about Chappaquiddick and Jaws, when crises flared at the hospital and the ferries groaned with traffic, when the wells threatened to go dry and the dumps to fill? How to preserve its own character as a reflective old Island paper and yet deal deftly, thoughtfully and comprehensively with news that was beginning to sound very much like news from everywhere else?

James Reston, twice the winner of the Pulitzer Prize, had traveled the world as a correspondent, bureau chief, columnist and executive editor for The New York Times. With his wife, Sally, he was a frequent summer visitor to the Island. “In the days of my youth,” he wrote in his memoir, Deadline, “some restless reporters, usually when they were tipsy or sore at some editor for mangling their copy, would damn the big city dailies and babble about retiring to edit or even own a little country paper.” Mr. Hough proposed the sale to the Restons because, he said, “I want it to go into a newspaper family and you have writing sons.”

From Washington Mr. and Mrs. Reston introduced the new technology of cold type, careful to replicate as closely as possible the old fonts of the letterpress days. They invested in computers, lifted the roof of the old office — once a poorhouse — and expanded the plant on the corner of South Summer street and Davis Lane, just across the lawn of their summer home. Later, under the Restons, would come the Pulitzer Prize winning sage who had retired to Katama from New Jersey, William A. Caldwell. They hired editors Phyllis Meras and Douglas A. Cabral, who began to wrangle with the problems of the modern world, and to explore the interests of the newest generation of Vineyarders and visitors, all the while holding fast to a fixed mission of the Vineyard Gazette — "to know what went before," as Mr. Hough once explained.

In the fall of 1975, the executive editorship of the paper was transferred to their oldest son, Richard Reston, formerly a correspondent with the San Francisco Chronicle and a reporter and bureau chief in London and Moscow for the Los Angeles Times, and his wife, Mary Jo (Jody) Reston, who served as business manager. Richard and Jody Reston became publishers of the Gazette on July 8, 1988.

Island Life

We come now to our own time, to the weekly judgment of the contemporary reader, and to the question asked at the beginning of this history: Why was it so important to have a copy of the Vineyard Gazette with the storm long gone and the rebuilding so plainly evident to all?

It’s worth remembering that the founding editor may have been the first man on Martha’s Vineyard to describe publicly and quite precisely what was so appealing about this place where he and his audience lived. He told his readers what was different about it. He said that the beaches were longer than Rhode Island’s, that the fishing was better than any other place along the coast, that the riding would suit any horseman.

The differences of Vineyard life captivated the Gazette forever after. Mr. Cooms wrote about them in his midnight stroll around the tented Camp Ground, Charlie Mac in his third visit to the agricultural fair, Mr. Keniston after witnessing the Katama fox hunt. Today every story begins with the implication that nothing quite like this has ever happened anywhere else in the world.

It is true that other villages stage farmers’ markets and hold county fairs. Other towns have carousels and brass bands. Other headlands have cliffs, other harbors have ferries and schooners, and other farms have draft horses and organic crops blowing in the summer breeze. You may find boards of selectmen all across New England, barn raisings, tribal pageants and historical groups storing the logs of whaling masters or saving grand old churches and country stores. On the mainland frogs sing in the springtime, drifts of snow seal the front door and leave bare patches behind a leeward corner. The wildest storms come from nowhere to send sheets of salt water racing over the rooftops, flexing the seaward faces of the oldest houses and leaving a jungle of wood and green leaves and wire on the street corner in the sickly sweet-smelling hours of calm that follow.

The hurricane of August 19, 1991, raked the coastline from the middle of Long Island out to Chatham and Provincetown. But people hurried to buy the Gazette because they wanted a record of one important thing, the thing the paper could be counted on to ponder first and last — why it was different here.

1 comment

1 comment

Comments (1)

Comments