There’s little to record in the history of the printer’s art between the invention of movable type in the early 1400s by Johannes Gutenberg and the first publication of the Vineyard Gazette some four hundred years later. In fact, if Joe Gutenberg could have been brought back to stand in front of the old Adams press still on display in the Gazette’s downstairs museum area, he certainly could have printed the first papers himself.

Gutenberg’s great invention was actually the precision molds from which bits of metal type could be mass-produced. These bits of type were arranged in lines, then in columns, and locked together under the pressure of wedges called quoins. Whole forms of type assembled in this piecemeal fashion were placed on simple presses for printing; after their use, the bits of type were washed clean and used again.

The museum that replicates Gutenberg’s original workshop in Mainz, Germany, contains a wooden model of his simple, sheet-fed printing press. The Adams No. 248 press that printed the Gazette in its first decades is made of iron, bronze and steel, but otherwise resembles the historic original in almost every respect.

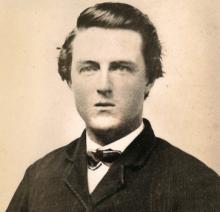

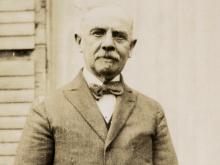

But if time stood still for the printer’s art between the eras of Gutenberg and Edgar Marchant, the Gazette’s first editor and publisher, the same cannot be said for the last century and a half. Printing has seen the coming of first the industrial revolution, then the electronic age and finally the information revolution in which virtually every element of human communication, including these very characters on the page, has been translated into bits of computer data.

Each major change in the printing industry has trickled down from the biggest publishing houses and daily newspapers, eventually reaching smaller papers such as the Gazette. Computing power that was once available only at major corporations and universities now fits on any desktop and can be purchased at your local office supply store. For the past two years, for the first time in its history, the Vineyard Gazette has been produced largely not with the use of specialized equipment built specifically for the newspaper trade, but with consumer electronics and simple, universally available software.

The Early Days

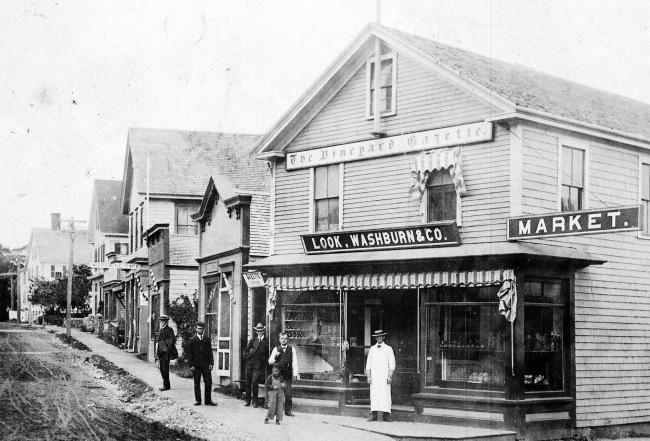

Volume 1, No. 1 of the Vineyard Gazette, published on May 14, 1846, was entirely a work of hand-set type. That is, every character of every word had to be picked by hand from cases filled with metal type. The edition was of four pages, five columns wide and 18 inches deep. “The dimensions are good and it looks all right,” declared an admiring William Roberts, the Gazette’s pressman, reviewing that first edition in a centennial story published in 1946.

Noting that the century-old Seth Adams machine was then still in use at the Gazette as a proofing press, Mr. Roberts wrote: “It has been said that a crew of three could work up a fair rate of speed on these ancient machines, and their work-and-turn labor paid off in excellent reproduction to which the long years have added nothing whatever in quality.”

From today’s perspective, Mr. Roberts’ “fair rate of speed” seems an extremely generous assessment of the capacity of that first press. Before a single copy of the Gazette could be printed, the page forms first had to be inked with large pads called ink balls. Then a sheet was laid on the forms and they were rolled under the press itself, which was actuated by pulling a heavy lever. The result, when the sheet was pulled away from the form, was a single copy of the Gazette - but only half-printed! Every sheet had to be turned over and printed again to make the other two pages. If a crew of three men produced 500 copies of the Gazette in a day’s work on the old Adams, that was work well done.

The editorial text of the Vineyard Gazette in those first years was set almost entirely in seven-point type. That’s about 25 per cent smaller than the type size you’re reading in this story, the Gazette’s now-standard 9 1/2 points. The Gazette’s first “line cut” illustration, appearing in November of 1849, depicted the Boston warehouse of Whiting & Kehoe, a clothing wholesaler. Notes Mr. Roberts in his centennial history: “The illustration for Oxygenated Bitters, for dyspepsia, asthma and general debility, appears, in April 1852, upside down, and it was probably a mistake, since it resumed its normal appearance in successive issues.”

Age of Boilerplate

In the early years of the Vineyard Gazette - indeed, for almost the whole first half of the newspaper’s 150-year history - there was time in the working week to write the community’s news, or time to print the weekly paper, but there was never enough time to do both. The savior of the weekly newspaper publisher in those years was something called boilerplate. This word is not used in the marine sense, as in the rolled steel used in ships’ hulls, but in the journalistic sense, referring to copy provided ready-made for use by newspaper publishers. Sometimes this copy was in paper form and needed to be set in type; sometimes it came ready-to-use in actual plates of type for placement in the printing forms.

Publishers everywhere resorted to boilerplate copy to fill at least some of their editorial space, because it simply wasn’t possible to spend the whole week reporting the news and then slap it into shape for publication on deadline day as it is now. Printer Bill Roberts wrote of this 50 years ago, in his centennial essay:

“‘How long does it take to make the Gazette?’ is a question fairly often asked. The answer is that it takes all week, and for some reason unknown to the staff it’s usually greeted by a look of mild disbelief. Why this is the reaction is hard to understand, unless it’s that people consider weekly newspaper production by the yardstick of daily newspaper issuance - instead of in terms of different problems and smaller staffs.

“The notion, never really downed, is abroad that we dawdle along most of the week, and then, after a few muttered incantations on Thursday, we prepare to print on Friday morning. This is correct as far as the muttering goes, but there isn’t any magic short-cut, and if Thursday is a big day, it’s so because of urgency and tenseness built up by a rapidly approaching deadline.”

Henry Beetle Hough, editor of the Gazette for more than half of this century, had this to say about boilerplate copy in his book, Country Editor, in a passage describing one morning during his early days at the paper:

“I looked over the boilerplate material and found that in the course of two or three weeks we covered such various topics as the following: the world’s most illustrious corpse, Admiral Pillsbury and his study of currents, the age of the moon, trees in the Sahara, Highland Mary’s grave, Luigi Illica, Baffin Land, wolf hunters, intoxicated cows, the ancient port of Ancona, Peter Lightfoot, the South African ovenbird, the monastery of Kogasan, reading aloud at home, and so on and so on.”

In those days - the early 1920s - the weekly Gazette ran to a standard eight broadsheet pages. In defense of boilerplate copy, Mr. Hough wrote: “I do not believe there was type enough in the office to fill all eight pages, and it is certain that the two girls, with all possible speed and skill, could not have set enough for four pages on Wednesday and four more on Thursday. In those days the Gazette came out on Thursday, but later we changed to Friday to permit more time for the processes of publication.”

Change Comes Slowly

The printing machinery Henry and Betty Hough found when they became publishers of the Gazette in 1920 had changed very little from that which produced the inaugural edition in 1846. The changes of the industrial revolution had indeed begun to make themselves felt in the printing industry during the latter half of the nineteenth century - but those changes took a long time trickling down to the smaller, community newspapers.

The cylinder press was an invention first used by The Times of London in 1814 - it could produce newspapers at the then-incredible speed of 1,100 sheets per hour. More than a century would pass before the Vineyard Gazette had equipment to match that printing power and speed.

In 1872, the Gazette acquired a hand-cranked, two-revolution Fairhaven press, so named because it was built in Fairhaven. Henry Beetle Hough wrote in 1975 of the advance the machine represented:

“The type forms were placed upon a flat bed, but now there was room for four pages. Inking was no longer by hand but by means of rollers which moved with the operation of the press and transferred ink from a trough or fountain which occupied its full width.

“Sheets of paper were fed from above, to pass around a cylinder of such a diameter that in two revolutions the whole sheet of paper would have been brought in contact with the type pages. Some earlier presses had an enormous cylinder - a drum cylinder it was called - so that a single revolution would suffice. But the two-revolution press was an advance. After the sheet of paper had been printed through the action of the cylinder against the inked type, the sheet of paper was seized by grippers and carried to a delivery pile at the rear. This method of transferring sheets was known as a butterfly delivery, and unless the grippers were timed with complete accuracy they would drop a sheet upon the forms where it would be ground to tatters before the press could be stopped.”

By the time the Houghs acquired the Gazette, the Fairhaven press was already old and obsolete. Mr. Hough wrote of its eccentricities in his book, Country Editor:

“In its day the Fairhaven had been a remarkable machine, but now it did its best work only with a sympathetic crew of four persons. That press was sensitive and would stand for a great deal of flattery but for no criticism whatever.

“Of the crew of four, one was required to turn the crank. Slow and easy did it. Somebody too strong and ambitious could jump the mechanism out of gear. I turned the press myself at times, and was surprised to discover that what I had taken to be an unskilled job really had its points. Another person was needed to feed the press, and this was Olivia, who had a delicacy of motion, a sort of swift competence, combined with an exceeding wisdom in the ways of the machine. She could even tell when something was about to happen. The trouble was that, by the time she had cried out, whatever was about to happen had happened. Still, it was helpful to have that admonitory yell.

“The third member of the press crew was less important. He was a boy, if one could be found, to sit in the rear of the old Fairhaven and straighten out the sheets as they were delivered by the fly. The press would deliver all right by itself, but the pile would be so drunkenly eccentric that someone would have to run all through it to straighten the sheets so that they could be fed into the press to print the other side on the final run of the week.

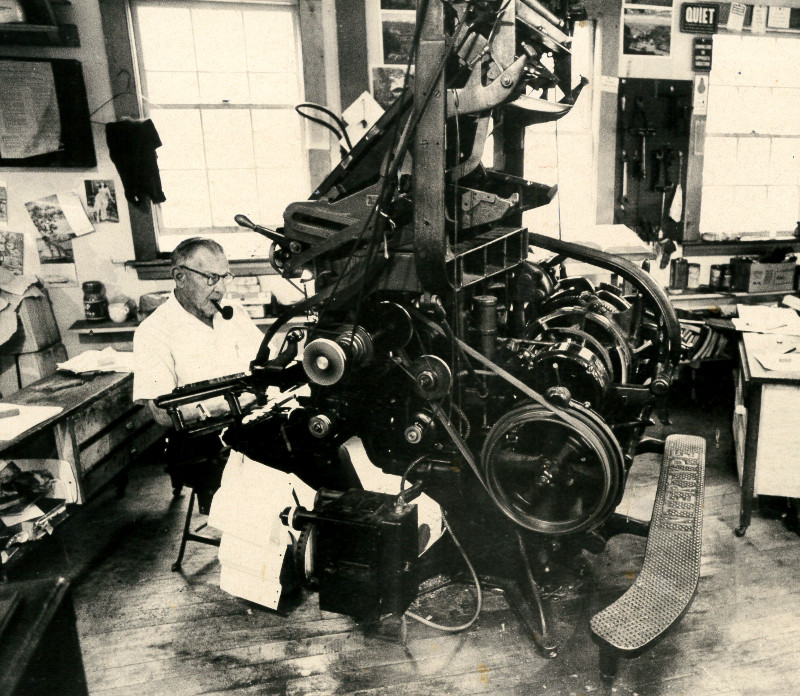

“The fourth member was, of course, [editor Charles H. Marchant] himself. It was he who mothered the press, watching it judicially with his cigar in the corner of his mouth, adjusting the ink, recommending just a little less haste or a little more smoothness of motion, moving here and there with an oil can. It was he who smiled on the press and said honeyed words to it, without which it would have stopped.

“All presses should be provided with a means by which the cylinder may be tripped, to skip an impression when a sheet goes in wrong, or all is not well. The Fairhaven had a pedal for this purpose, but sometime in the far past it had got out of order. Some printer of the period had discovered that the press would operate all right if a heavy weight were suspended from the pedal and allowed to rise and fall with the revolutions of the machine. This permanently negated the purpose for which the pedal had been provided, and it also introduced a new hazard. The weight was exceedingly heavy, and at least once during every run it broke loose and crashed to the floor. That crash was hard enough for the taut nerves of the Gazette staff, but what it must have been for customers in the grocery store downstairs I have never been able to imagine. Mr. [Marchant] was philosophic about the weight, more so than anyone else because of his general attitude of indulgence toward the press, and he was always trying new kinds of cord or wire. He never found one which could stand the strain. The weight always crashed, and we felt that our lives had been shortened.”

Whitlock Years

The Houghs began shopping for a press to replace the old Fairhaven early in their tenure at the Vineyard Gazette. It had already served the newspaper for more than twice the span of years served by the first Adams hand-press.

The Houghs, through a friendly foreman at the New Bedford paper, learned of a second-hand Whitlock machine which promised to carry the Gazette’s printing operation, for the first time, into the machine age. The Whitlock machine operated on essentially the same principle as the Fairhaven, but was driven by an electric motor and capable of producing 1,000 copies per hour - this speed was easily twice that of the Fairhaven, but still, the new press could print only on one side of the sheet.

Getting the old Whitlock machine to the Island proved to be the first of many challenges and setbacks for what turned out to be the shortest-lived of all the Gazette presses. Recalled Mr. Hough in Country Editor:

“We had a concrete foundation prepared in the new building, and began to get ready to transplant the Gazette. Things were going along well when, one afternoon, the telephone rang and somebody said, “You expecting a printing press? Well, it’s gone through the wharf up here at Vineyard Haven.” Betty and I got in the car and drove up. I was expecting to see the Whitlock languishing in the harbor, but fortunately it had not gone all the way through the dock.”

Neither Mr. Hough, nor Mr. Roberts in his centennial essay, were kind in their recollection of the mechanics who installed the Whitlock press at the Gazette. “I had never seen the Marx brothers at that time,” wrote Mr. Hough, “but if I had, the mechanics would have reminded me strongly of them. Their lighthearted assurance did more to undermine confidence than anything I have ever known. It turned out that they were competent enough, except for a tendency to leave out parts that would not be missed right away. For instance, they did not bother to include the brake, and the omission was to cause us distress for years.”

Of the Whitlock press, Mr. Roberts wrote: “The vibrator gears had been stripped somewhere along its wild past, and the roller sockets were in a condition which allowed use of but two, instead of four, form rollers. Ink distribution had therefore a handicap to hurdle which it couldn’t quite jump at times. In addition, it was a type of press unfamiliar to anyone present, and more than kind words and a friendly pat were needed.”

Age of Linotype

The 1920s were a time of transformation for the Vineyard Gazette, not because of the Whitlock press but because of another technological advance brought here by the Houghs - the Island’s first Linotype machine.

The Linotype was the invention of a German-American, Ottmar Mergenthaler, in 1884. This machine had the ability to do something truly revolutionary: It could cast an entire line of type (hence the name) in one piece of metal.

To appreciate the advance represented by the Linotype, you need to understand a bit of the work involved in the old process of hand-set typography. The process went like this, according to a story in the 1975 Gazette by Henry Beetle Hough:

“Compositors or typesetters stood or sat on tall stools in front of compartmented cases in which type characters representing different letters were conveniently kept. The small ‘e’ was the most frequently used type, and therefore it had the largest and most accessible compartment. ‘Lower case’ came to be the phrase describing small letters, for they were nearer to the typesetter. ‘Upper case’ or capital letters were above.

“Swiftly moving fingers picked out the letters - in the form of individual types which had come originally from a type foundry - and composed them to follow in order, word by word, space by space, and sentence by sentence, the ‘copy’ which was to appear in the newspaper.

“The type set by individual compositors was assembled into complete stories on long trays or galleys. A sponge was kept handy with which to wet the type so that the individual letters would stick together and the risk of spilling or dropping out - a great risk where so many small bits of metal were involved - was minimized.

“Each galley of type was inked with a hand roller and a strip of paper taken on a proof press operated by a hand lever. These were corrected by hand, and type was then transferred into column lengths, defined and held by brass column rules, until whole pages were ready for printing.”

This is the process which the Linotype revolutionized, beginning in 1920. The new machine cost the Houghs the then-lofty price of $3,500, even though it was a rebuilt machine. “The serial number was 1689,” wrote Mr. Hough, “which indicated that the soul of the machine dated well back into the early days of the company. But as a matter of fact, most of it was assembled of new parts, and they were all fresh and shiny, and of course there was nothing better anywhere around with which to compare it.”

The genius of the Linotype was that it used tiny circulating molds, called matrices, which could be fitted together to make, from molten metal, a whole line of type in a single piece called a slug. As Mr. Hough recalled it in Country Editor, the word “circulating” was a truer description of the matrices than anyone had expected:

“We found matrices on the end of the steamboat wharf, under the bed at home, in the middle of Main street, out in the woods, and in the laundry. Miles away from the Gazette office we would see a familiar glitter in some improbable place, and we would know that we had found another matrix.”

For all its ways of sending matrices skittering, the Linotype transformed not only the printing operation but the whole business of country journalism at the Vineyard Gazette. By taking hours away from the labors of hand typesetting, the Linotype freed time for the gathering and writing of news, and enabled the Gazette to lighten its reliance on boilerplate copy and deepen its coverage of community life.

The Gazette, newly equipped and with the fresh energy of the Houghs, began for the first time in its history to issue 10-page and 12-page editions. They were not always elegant creations during this time of transition, Mr. Hough recalled, but somehow the papers always appeared on time:

“By some marvel the larger issues came out, but they were a hodgepodge. Mr. [Marchant] picked up whatever type was ready and put it into the first hole, so the local news of one town would be trailing all through the paper. If you were looking for something you could not expect to look in just one place. You had to look everywhere.

“One reader wrote in to discontinue his subscription, remarking that the paper was the poorest he had ever had the pleasure of reading. We printed his letter, and Betty put on the caption: ‘Still He Calls It a Pleasure.’”

Island Shrinks

The Linotype is only one of many examples of the way changing technologies have affected the way the Gazette has served its Island community over these 150 years. Other vivid examples are the telephone and the automobile, which together conspired to make the Vineyard a much smaller and better-connected place.

From its beginnings, the Vineyard Gazette has been published in Edgartown, the shire town of Dukes County. This happenstance of location has little influence anymore on the newspaper’s work, but in the early days a trip up-Island was a major outing, and reporting on events only a few miles from Edgartown was difficult.

A six-line heading of “Fire! Fire!! Fire!!!” topped a detailed story in the March 8, 1867, edition of the Gazette about a conflagration in Edgartown which now is largely forgotten to history. The subhead declared: “The Whole Town Endangered But Miraculously Saved.” By contrast, most of Tisbury was destroyed in a great fire on August 11, 1883; the Gazette of the next week had only a follow-up story on the disaster, placed on Page Two and running under a simple, one-line head: “Vineyard Haven.”

It wasn’t until years after the great fire that the first network of telephone lines began making rapid communication possible on the Vineyard. When Bell Telephone first came to the Island, the three down-Island towns were connected with only a single pair of wires. “That,” wrote the late Joseph Chase Allen in a Gazette story, “constituted the entire Island system in November of 1898 when the Portland gale wrecked the pole line over East Chop and Frank Golart of Vineyard Haven, the only outside man employed, picked up the wires, spliced them where necessary and reopened the line by stapling the wires to fenceposts wherever they were convenient.”

The expansion of the Vineyard telephone system came quickly in the early years of this century, first connecting such important town centers as post offices, then connecting the homes which lay along the wire routes. Those early telephones were run by switchboard operators who would signal individual receivers by particular patterns of rings. “The operator was an accommodating person in every respect,” wrote Mr. Allen. “She would call George Smith, as requested, and when Mr. Smith appeared at his telephone, he might well be asked to summon a neighbor, who had no phone, and this also was done again and again.”

Dr. Charles F. Lane, a Vineyard Haven doctor who attended to many families up-Island, lobbied vigorously with the Bell company on the need for lines running up the Middle Road. When the utility declined, the good doctor went into the telephone business himself, and for years was a familiar figure up-Island in his top-hat, climbing poles to maintain his private telephone system. The Bell company finally established its own Chilmark exchange in 1926.

Duplex Press

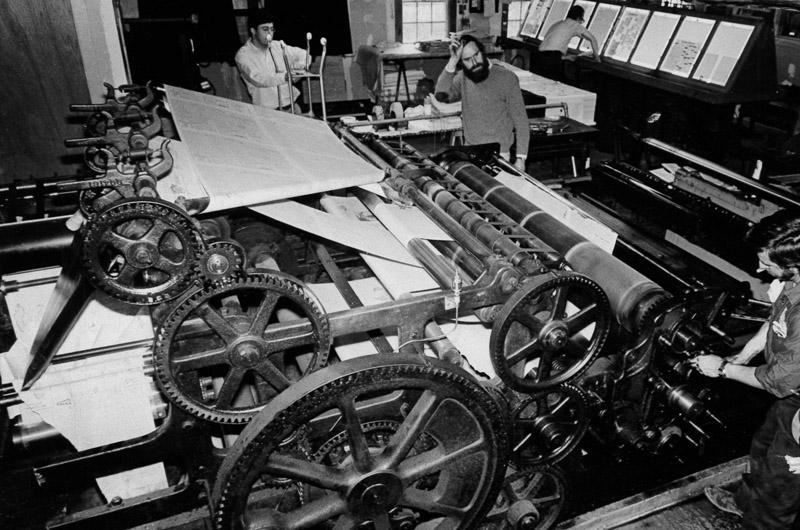

The first decade of the Gazette under the leadership of the Houghs was a time of constant change. The second-hand Whitlock press lasted only until 1929, when the Houghs broke the piggy-bank and purchased a brand new Duplex flat-bed perfecting press, an 18,000-pound marvel built in Battle Creek, Mich., which included many then-wondrous advances.

The Duplex printed not from individual sheets, but was a web press using continuous rolls of newsprint and producing 3,000 finished papers per hour. Not only could the Duplex print on both sides of the sheet simultaneously for the first time in Gazette history, but it also included for the first time a folding unit so that each copy of the paper no longer had to be folded by hand. An image of the new Duplex proudly filled five columns at the center of the Gazette's front page on the week of its introduction.

Meanwhile, in 1927, the Gazette had purchased its second Linotype machine, this one a far more advanced Model 14, which could produce not only newspaper text but much larger headlines as well. Enthused the Houghs in their announcement of this new arrival: “Most advertising matter is within the range of this machine, with the result that more attractive display and much greater capacity is made possible. The improvement in the appearance of the paper and in service to advertisers brings the Gazette in line with the best equipped and most modern newspapers.

“With two Linotype machines it will be possible to handle seasonal increases in news and advertising volume with greater ease and speed. Mechanical limitations will, to a large extent, be removed.”

Reflecting on the departure of the old Whitlock in an anniversary editorial in 1929, Mr. Hough wrote: “The old press did no folding whatever. We wonder if subscribers have ever realized how personal a product the Vineyard Gazette has actually been; not a copy of the paper has gone from the office but that every fold was put in it personally by an editor, publisher, business manager or member of the staff. No matter what opinion may be outside, the Vineyard Gazette staff, engaged in folding, cutting the pages, and inserting some 2,200 or more copies of the paper on a moist and slow-moving Friday, has often concluded that $2.50 a year was a very moderate charge indeed for a subscription.”

News Twice Weekly

The two Linotypes and the new Duplex press changed everything. The first and most dramatic steps by the Houghs to take advantage of their new technology was the introduction, in 1929, of the summer Tuesday edition of the Vineyard Gazette.

The first of the Gazette’s Invitation Editions, at an ambitious 16 pages, appeared in April of 1933. The first Directory Edition followed that same June. Both special editions have been fixtures in the Gazette’s publishing calendar ever since. All of these new initiatives were, in the words of William Roberts, “made possible mechanically only by the new press.”

During the 1930s, the Gazette suffered lean years along with many other businesses. Advertising lineage was low, but circulation of the paper held up well. In July of 1932 the Houghs noted with pride in a front-page bulletin that the trusty Duplex had printed a run of 2,350 copies. By the centennial year, that figure had grown to as much as 4,500 in the summer season.

The Gazette purchased a Ludlow Typograph machine for its back shop in 1938, which enabled the newspaper to add a number of new and bolder advertising typefaces to its mix.

Problems of Illustration

With its new press and typesetting equipment, the Gazette of the 1930s had the problems of printing the written word pretty well licked, at least by the technological standards of the day. But letterpress printing, which works on essentially the same principle as the familiar rubber stamp, has its greatest limitations when it comes to introducing graphics to the newspaper page.

For many years, photo engravings were beyond the reach of the Gazette back shop, having to be shipped off-Island for production. This meant that photos taken on deadline were impossible to include in the newspaper.

It wasn’t until 1966, in the last years of letterpress printing at the Gazette, that the newspaper acquired its own Fairchild Cadet Scan-A-Graver. “Since previously the Gazette had had to send all engraving work off-Island,” a notice in the paper proudly announced, “the new machine will reduce considerably the time between the reception of a photograph and its reproduction in the newspaper.”

Meanwhile, the Gazette took advantage of local talent to use an artistic medium which lent itself perfectly to the technology of direct impact printing - the linoleum block print.

Wrote Mr. Roberts in his centennial history:

“‘Sidney Riggs’ justly famed linoleum block prints started to illustrate the pages of the summer of 1934, art work of high quality which received a great deal of attention and praise. We still prize a ‘gallery’ of the proofs.”

And in 1939, the Gazette began illustrating its pages with the linoleum cuts of Bill Abbe, whose work was also appearing in The New Yorker.

Age of Offset Printing

But even as they were enjoying their new letterpress equipment, the Houghs knew that change of a revolutionary sort was inevitable for the Gazette. The world of printing was moving away from hot type to a form of printing called offset lithography - a form based almost entirely on photographic images.

Lithography, a form of printing based on the fact that oil and water don’t mix, was actually invented in the late 1700s - again by a German, Alois Senefelder. He drew a design with a grease pencil on smooth stone, wetted the stone and then rolled it with ink. The oil-based ink adhered only to the greasy image area. Finally he pressed a sheet of paper to the stone, taking away the image. This was an excellent method of printing, but it took the breakthrough of offset lithography to make it viable as a mass communication tool.

Today, thin plates of aluminum have replaced Senefelder’s stone, and the image is first picked up by a rubber roller - the offset roller that gives this printing technology its name. The offset roller places the image on paper, usually fed by continuous rolls just like those that fed the Duplex press.

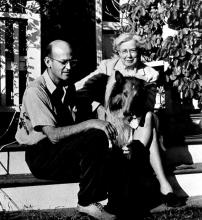

Henry and Betty Hough saw this change coming for many years, but they did not see how to manage it for a small community weekly paper. Even today, most weeklies do not own their own presses, instead taking their pages to the dailies in their area which job out their services when the presses have free time. But the Island was an isolated place, and cutting off the production process a day early to provide for the trip to a printer was unacceptable for the Gazette.

Mr. Hough wrote in an almost despairing tone of this problem in his 1973 introduction to a new edition of his book, Country Editor:

“My wife and I began our career on the Vineyard Gazette with hand-set type, a primitive press turned by a hand crank, and a press-run of about 600 copies. Gradually we acquired the new tools we needed: the simplest Linotype, $3,500; a more versatile Linotype, $4,000; a flat-bed perfecting press, $6,500 - in 20 years an investment, say, of some $15,000 and a paid circulation of about 3,000. We were doing well. Our years had seen struggle but also contentment.

“So far as the weekly paper in the small town is concerned, the terms have become harder. A press such as ours is no longer made. Linotypes are no longer manufactured in the United States. The invention of Mergenthaler which revolutionized the printing industry has been relegated to history along with the movable types of Gutenberg. Instead of a $15,000 investment gradually accumulated, the prospective owner-publisher must have, say, $75,000 and have it at once, because he needs cold-type composition and an offset press. The mass world has gathered up its technical resources and vast population and is moving on to wider complexities in the use of computers and laser beams for printing.”

The answer to the Houghs’ problem came in the new stewardship of the Gazette by James B. (Scotty) and Sally Reston, who became the newspaper's owners and publishers in 1968 and who, in 1975, purchased a new, three-unit Goss Community press and ushered in the era of modern offset printing.

The Goss Community represented the most remarkable single printing advance in the history of the Gazette. It was capable of printing 12-page sections at the blinding speed of 14,000 copies an hour – easily five times the speed of the Duplex which had served the paper so faithfully for almost half a century. And with the addition of a fourth unit in the spring of 1977, the Goss press was able to print full 16-page sections in a single run.

Announcing the shift to offset printing in January of 1975, the Vineyard Gazette reported:

“Change will be greatest in the matter of production. Speed and flexibility are the hallmarks of phototypesetting and offset printing equipment. The Gazette’s Linotype machines, operated by highly skilled men, can produce six or eight lines a minute. The new machines set type from coded paper tape at the rate of 60 lines per minute. The typewriter-like keyboards used to perforate the paper tape are quick enough to accommodate the speediest typists.

“When a complete story’s been reduced to holes on the tape, a computer-driven typesetter reads the code very quickly, justifies each line to the required column width, and using very high speed photography prints the finished product on long narrow strips of photographic paper. This is developed with chemicals, and the latent image of the column of type becomes visible.

“When the computer-typesetter is busy there is a red light which tells you so. Most of us at the Gazette believe the new equipment is smarter than the old, and some are afraid it’s smarter than we are.”

Seven Tons of Lead

By the time of the Gazette’s transition to cold type, the paper’s Linotype and Duplex equipment was thoroughly obsolete. Neither the press nor the typecasting equipment were being manufactured any longer, and skilled operators were almost impossible to find.

In the course of the changeover, the Gazette found itself with between six and seven tons of typesetting lead which was no longer needed. What to do? Much of the lead found an appropriate new home in the keel of a double-ended Maine pink sloop built for George M. Moffett Jr. of Edgartown by David Dana of Dana Boats in Vineyard Haven. Announced the Gazette on Jan. 31, 1975:

“Lest the unique source of the sloop’s ballast be forgotten in times to come, Mr. Moffett will install a fitting tablet on the surface of the lead; the front page of this, the last letterpress edition of the Vineyard Gazette, preserved in clear plastic for the ages, will greet the unsuspecting bilge inspector’s flashlight beam.”

Computers in the Office

The first phototypesetting machines at the Gazette were a pair of refrigerator-sized Compugraphic tape-reader units named Harold and Maude by the back shop staff. They could be called computers only by a generous stretching of the term. Basically they read the tapes perforated by a typist working from copy written by reporters at their manual typewriters; inside the machines, a strobe lamp sent pictures of letters flashing in neat rows onto photographic film which, when developed, became long columns or galleys of type for the newspaper.

Harold and Maude lasted until 1982, when the Gazette installed a system built by the Harris Corp. which for the first time could actually be called a computer network. Perforated paper tapes and readers were gone. For the first time, typists sat at video terminals on which news stories glowed in eerie green and were stored on eight-inch floppy disks in a pair of CPUs called MicroStors, which the Harris Corp. technicians described as “the traffic cops of the whole system.” Total memory capacity of the system was the then-phenomenal figure of two megabytes.

Because of its space constraints, the Gazette made its transition to the first Harris system on the fly - hauling out Harold and Maude one Friday morning in May of 1982 and wiring up the new equipment the same day. The Harris Corp. experts said they’d never seen a newspaper try to install a new system, program and debug it, learn to use it and produce a newspaper on it all in the same week. Wrote the Gazette in a story on the change: “They left the Island, no doubt, with a better understanding of why newspapers avoid this strategy.” The production staff spent a solid 30 hours on its feet Thursday and into Friday, but the April 16 edition came out on time.

Wrote the Gazette: “It’s a powerful system, in some ways a system only as good as its operators, and we still have a lot to learn. The office echoes with new words which grate against the soft contours of the circa 1760 walls - words like downloading, default files, format control codes, floppy disks and even a new and horrifying verb - keyboarding.”

The electronic revolution was confined entirely to the back shop until the spring of 1984, when the Gazette moved its newsroom into expanded quarters built above the press room and production area. This expansion made room, for the first time, for a network of Harris Model 1420 terminals at which reporters could actually enter their stories directly into the computers. (“Just like on Lou Grant,” enthused one visitor to the office that spring.) These first reporting terminals were notable for their susceptibility to static electricity Ñ a writer crossing the newsroom carpet and sitting down at the keyboard could transmit a shock that would magically erase a whole story. They will also be remembered for their habit of blowing up their power-supply circuit boards; when a 1420 unit’s transformer blew, the machine emitted a column of white smoke that looked positively Biblical.

The Gazette’s typesetting units during this period were Varitype machines that operated on essentially the same strobe-and-spinning-negative principle as the first Compugraphic tape readers. The Varitype units failed often, most regularly burning out the little motors that made their type font wheels spin. After the first year the Gazette did an end-run around the Varityper parts department, located the Pittman motor company and started buying the tiny motors direct from the factory in sets of 10.

The Gazette’s next major computer transition came in 1986, when it installed a second-generation Harris system built around a central computer called the 8300 unit. With this new system the paper’s storage capacity grew from two megabytes to 50, and its new Compugraphic printers (happily much more reliable) could produce 300 lines of photographic type per minute instead of 50.

All these systems from Compugraphic and Harris and Varityper were specialty items for the publishing trade, costly machines made exclusively for newspaper production work. The next change in computer systems - made in the spring of 1994 - brought the Gazette into the era of desktop publishing, with a network of Macintosh computers and a pair of large-format laser printers.

Announcing this latest change in April of 1994, the Gazette wrote: “The new Macintosh network has transformed the process itself, moving whole stages of newspaper work from the back-lit light banks of the production room and onto the glowing screens of computer workstations.

“Each page of this newspaper is stored in the Gazette computer network’s memory, not as letters of the alphabet, but as a grid of pixels, either black or white, packed almost 1.5 million to each square inch. To accomplish this, prodigious memory capacity and computing speed are required, but these are commodities available in abundance from the computer industry today. The new system’s memory has expanded by a factor of 30, to 1.5 gigabytes, and even the reporters’ writing terminals have more computing power than the mainframe at the center of the previous system.”

In the span of six years, the Gazette’s Harris 8300 system had gone from cutting-edge to Cro-Magnon - when the new Macintosh system was installed, the old 8300 machine went not to the second-hand market but straight to the dump.

The Gazette did manage to find a buyer for the huge, chemical-filled processing machine that had been used for developing the galleys of photographic type. Gone was the expensive film and chemistry, replaced by plain paper and the occasional toner cartridge in the new laser printers.

The new system, now familiar after slightly more than two years, is used not only in production of the Vineyard Gazette, but also for the newspaper’s sister publications, Martha’s Vineyard Magazine and the Best Read Guide.

Looking Ahead

In 1996, most of the advances made possible by the computer revolution are already in use at the Vineyard Gazette. Scanners enable us to bring photographs and drawings right onto the page as digital information, and the publishing software, Quark XPress, gives designers a godlike power over the printed page.

Computers continue to grow faster every year, but reporters still have to compose their stories and designers still have to decide how they want their pages to look. People are now the slowest links in the production chain, and this is as it ideally should be Ñ increasingly, the tools of newspaper publishing are becoming transparent to the user.

The Gazette’s Goss Community presses, lovingly maintained and operated by pressman Brian Mooney, are work-horses and promise to last indefinitely. One change that probably lies somewhere in the future has to do with the preparation of plates for those presses; machines already exist to make plates direct from computers, bypassing the stage of laser paper printing entirely, and someday those machines will be affordable enough for weekly publishers to buy.

This winter, jumping solidly into the information age, the Gazette launched its own site on the World Wide Web and began accepting e-mail at its new address: gazette@vineyard.net. No doubt with time these new addresses will begin to sound as familiar as the computer terminology that’s been around now for all of a decade or so.

In this era of rapid advance, perhaps it is better not even to try predicting the future. Henry Beetle Hough had the right idea in 1929, when he concluded his announcement of the new Duplex press with this thought:

“It is best, perhaps, to refrain from promising too much for the future; let us be content to say that the Island newspaper is better equipped for the duties it should perform and it is to be hoped that the future will speak for itself.”

1 comment

1 comment

Comments (1)

Comments