It’s a little after noon on a wintry Wednesday, and Alex’s Place is hopping. Normally the 5,000-square-foot space, spread out over two floors in a wing of the YMCA, across the street from the Martha’s Vineyard Regional High School, is quiet until school lets out at two.

But this is the week of midterms and after being released each day from prolonged blocks of rigorous morning testing, a sizable group of teenagers has shown up to decompress.

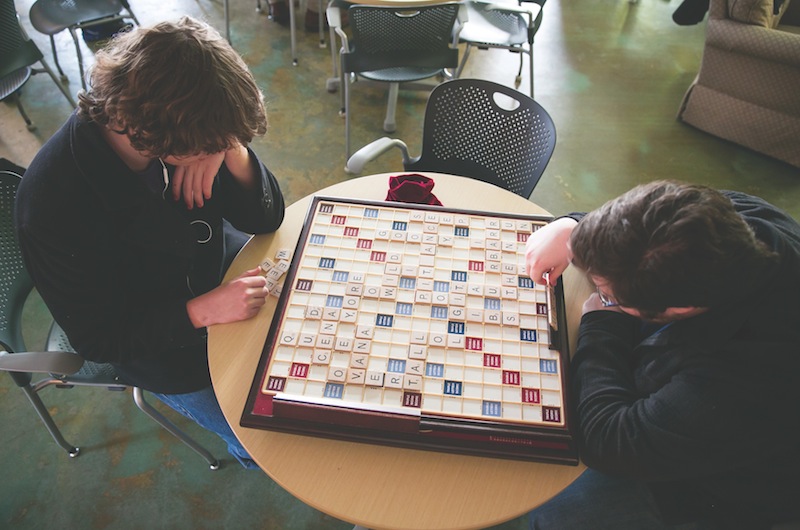

Near the full kitchen, a small crowd gathers around a television for a video game showdown. At the counter behind them, one girl stands over another, braiding her hair. A few kids in warm-up pants and MVRHS jackets pass through on their way to working out in the gym. In the center of the room, a group of students is quickly drawn to a mismatched collection of comfortable chairs, where they flop. If there was a sign here, it might read, Caution: Normal Teenagers at Work.

“Kids can come through this door and do absolutely nothing,” Tony Lombardi, director of Alex’s Place, said moments before the horde descended. “There are all of these different opportunities available, but they can come here and sit down and just chat.”

After being housed in temporary spaces for a few years, Alex’s Place found a permanent home at the YMCA in 2011. The $1.2 million facility was made possible thanks to a foundation gift from Jacques and Marfi Gagnon, a couple with Vineyard ties whose daughter Alexandra died of a heroin overdose in 1998 at age 23. The Gagnon family vision that led to the creation of Alex’s Place was ahead of the curve, coming many years before the opiate crisis and epidemic that now is gripping the country, including on the Cape and Islands.

“What was unusual about Alex was that she did not have any of the stereotypical signposts that you would anticipate from somebody struggling with any drug problem,” Lombardi said. “She was at the top of her class, she was an avid athlete, she came from an extremely reputable family. Her drug use flew under the radar and then they lost her.”

Approaching 60, Lombardi is bald, expansive and gregarious. A self-described open book, he’s gay, a recovering heroin addict (he’s been clean since 1984) and the product of a difficult family upbringing. For a time, he was homeless. “My personal experience lends itself to being sensitive to struggles that young people go through on a lot of different levels,” he said. “I was in the punk rock scene. I’ve heard it all. There’s not much that you could say to me that would really freak me out. Like, even remotely.”

As a former educator — he spent 29 years as a sign language interpreter and special education teacher at the high school — Lombardi has been around adolescents long enough to know what they want in an after school space. “Kids clique together,” he explained. “So in order to get them all in the same room there have to be different areas.”

In addition to the kitchen, lounge areas and computer lab upstairs, there is a lower level at Alex’s Place boasting a full recording studio and cabaret theatre where community events are held year-round.

With a mission to “teach without getting caught teaching,” he and assistant director Laurel Redington see themselves as mentors to the nearly 500 teenagers they serve each year. Last year, Alex’s Place saw 480 unique visits and 2,300 repeat visits by adolescents aged 13 to 18. The high school student body hovers just below 700.

“We integrate ourselves into the population and have been very much accepted by these kids,” Lombardi. “Our job is to participate. Not to be their friend, but to be their mentors, and to listen for cues and signposts of hidden struggles.”

The hidden struggles change from year to year but the major players stay the same: academic pressures, social anxiety, family troubles, substance abuse, and what Lombardi terms this year’s buzzwords: anxiety and stress.

“There are programs popping up everywhere to address stress and anxiety in young people,” he said. “Kids are self-medicating, which is why there’s such a dramatic increase in marijuana use — even though on Martha’s Vineyard there’s always been a lot of marijuana use — and I think that’s why pill use has become so popular.”

And while Lombardi doesn’t see much, if any, first-hand evidence of drug use inside the walls of Alex’s Place, he hears things. He knows what’s happening, and in many cases he knows where it’s happening. At the center of a burgeoning “campus of positivity,” the YMCA aims to be a safe alternative for adolescents looking for ways to stay engaged. But outside his doors, there isn’t much Lombardi can do.

“My jurisdiction is this building,” he said. “There are things out there that need to be fixed. Things in our neighborhood.” He shook his head in the direction of the parking lot behind the ice rink next door, where a fleet of sightseeing buses is parked off-season. “Kids are getting high [on marijuana] out there quite frequently,” he said “They go out in the woods. Whoever owns that property needs to know that.”

He continued: “I think that somewhere along the line we, as a society, jumped track and said, if you’re feeling these feelings — if you’re unable to focus, if you’re having a hard time sitting through class, you’re fidgety, you’re hyper — just take this pill and it will fix you. We’ve instilled in these kids the idea that the fix is something that they seek outside themselves. Something that isn’t therapy or communication.”

On the Island these days, where there is renewed emphasis on creating a better early intervention network for teens, that view is changing. The Island Wide Youth Collaborative, a new nonprofit organization developed by Martha’s Vineyard Community Services with support from the YMCA, the high school and other local agencies, aims to encourage communication by providing more support for families in crisis.

With a sparkling new facility adjacent to Community Services, IWYC plans to introduce a variety of family-focused initiatives. Programs include substance abuse support groups, practitioner trainings and nutrition workshops.

“In the few short months that we’ve been working with families we’ve made a tremendous impact,” said director Susan Mercier. “Just to be able to say to families, ‘We’ll make these three calls for you.’ . . . . You can just see the relief in their body language.”

Now at Alex’s Place, if Lombardi suspects that one of his kids is in trouble, he is able to make connections via the Island Wide Youth Collaborative.

“I think the blessing is that we have a safe place for kids to land at Alex’s Place, and the IWYC is a safe place for them to be able to seek help,” he said.

On the whole, Lombardi sees progress and hope. He says teens are more open minded and accepting than ever before. Alex’s Place is the only facility on the Island with gender non-specific bathrooms, for example.

He turns philosophical. “Children are born perfect. They are born flawless,” he said. “They are born without anxiety and without stress. So what is the message that’s being given by the family and the schools? Kids are coming up to us and saying: ‘I have to figure out what I’m going to do with my life!’ ”

At Alex’s Place, teens are encouraged that while it’s important to dream, it’s not essential to have a plan, particularly if having a plan leads to anxiety and stress.

It’s a lesson Lombardi took from the decidedly unanticipated trajectory his own life has taken.

“I didn’t see any of this coming in my younger days,” he said, surveying his domain, the empty chairs and tables that would soon be thronged by teens. “I never imagined anyone would give a gay heroin addict the keys to a building full of children. Who could possibly imagine that?”

This story appears in print in The Vine, a Vineyard Gazette publication in mailboxes and on newstands this week.

7 comments

7 comments

Comments (7)

Comments