“Cap’n” Seth Wakeman Jr. of Menemsha reports that representatives of the Oceanographic Institution at Woods Hole got “some of the best whale pictures ever taken,” during a recent visit to the Island. In addition to taking still and movie shots, the scientists also had excellent luck in recording the sounds of the whales which have been seen off Menemsha Bight and Gay Head in recent weeks.

The group of oceanographers came over in one of the institution boats, the Risk, and were piloted by Capt. Stanley E. Poole of Chilmark. They visited the Island for one day last week and were here for four days the previous week.

“Cap’n” Seth’s verdict is borne out of this release from Jan Hahn of the Oceanographic. As to the pictures - those reproduced here were taken by a Cape Cod cameraman.

A First for Right Whales

Last week oceanographers recorded for the first time underwater sounds made by baleen whales, when three right whales, ranging in length from thirty to fifty feet were so considerate as to spend about a week within ten miles of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution on Cape Cod. The right whales, one of the oddest looking whales in existence - hunted almost to extinction by the middle of the eighteenth century - stayed within a few hundred feet of the beach in Menemsha Bight.

Although it has been known for at least eight years that toothed whales frequently made a great variety of sounds, attempts to establish this for baleen whales had not resulted in clear and unequivocal evidence. Last week, in the presence of three right whales, sounds were heard and recorded which had never before been noticed in these waters. As far as was known, this is the first time that anyone had been near a right whale with underwater listening equipment. Other baleen whales, such as the Pacific grey whale, the humback, and finbacks of several kinds, had been listened to with negative results.

The whale’s appearance was first reported in the Vineyard Gazette, where it was noticed by Capt. Stanley E. Poole of Menemsha, who had been out whale “hunting” off Bermuda with Oceanographer William E. Schevill, to attempt sound recording of humpback whales. In the absence of Mr. Schevill, who was chasing grey whales on the Pacific coast, Captain Poole, assisted by Research Associates Karl E. Schleicher, John G. Bruce Jr., and Lincoln Baxter 2nd, and Photographer Robert Brigham, placed on the thirty-five foot launch Risk sensitive sound receiving tape, a tape recorder, and a portable generator.

Deep, Loud and Throaty

During the next four days, the Risk spent the daylight hours hove to in Menemsha Bight listening to underwater sounds and observing the whales’ behavior. Deep, loud, throaty sounds, noises reminiscent of cat fights and squeals, were recorded on two of the four days. Sometimes the blowing of the whales could also be heard on the sound equipment. Fortunately, boat traffic was light and propeller noises of passing fishing boats blocked the whale sounds only occasionally.

The whales were identified as Eubalaena glacialis, a right whale, by Dr. Richard Backus, biologist of the Oceanographic. This whale is also known as the Biscayan whale, being chased by the Basques from the fourteenth through the sixteenth centuries, and later by the Dutch, who called the whale Nordkaper. A similar whale is found near Australia and off Japan.

The right whale, named for being just “right” for whaling in the old days - it has considerable blubber and long baleen and floats after death - could not stand several hundred years of whaling by Basques, Dutch, English, and the New England whalers. It was almost extinct by 1750. Now protected by international law, it appears to be coming back, and generally ranges from Iceland to Nova Scotia in the summertime. During the winter months it has been reported off Bermuda and off Daytona and St. Augustine, Fla., in March, 1950, while last winter one or two were sighted off Barnstable in Cape Cod Bay.

On several occasions oceanographers on the launch Risk took up their sound gear to approach the three whales for photographic purposes. They could be approached to within a few feet and would swim right alongside the boat at a speed of about 2 to 4 knots.

Friendly Fellow Travelers

Of a non-aggressive type, they could easily have given the Risk a good shove with their enormous blunt head or the 10 to 12 foot wide tail, but seemed to evade our launch and any chance of collision, narrow as that was on several occasions. Their evasive movements were quite agile, and the frequently came to the surface to blow, providing a wonderful opportunity for close observations.

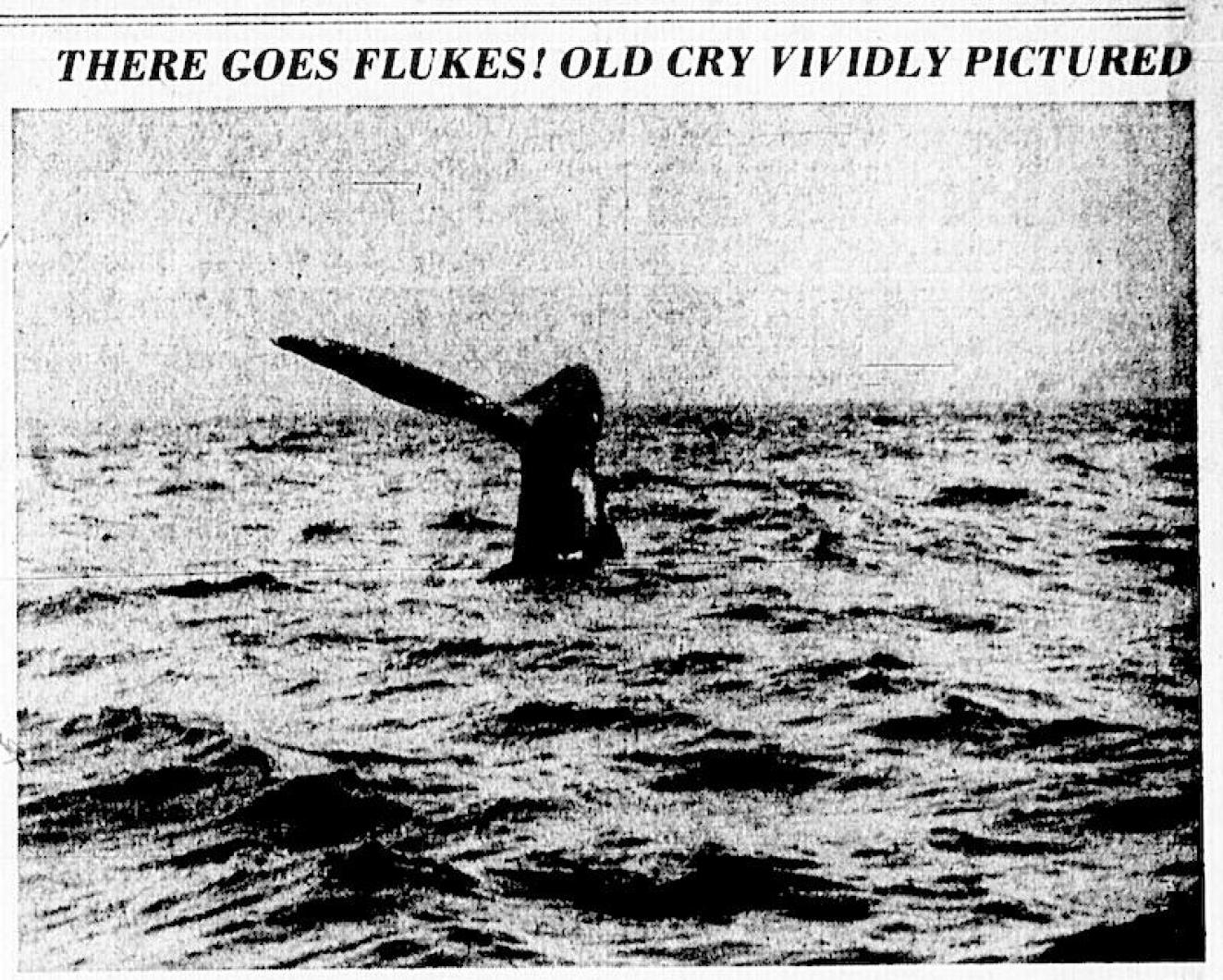

Their two blowholes (toothed whales have only one blowhole) would spout about 5 to a good 10 feet high and on occasion the spray would cover the camera lenses. It was noticed that the right whales’ spout did not have “B.O”, which can be most obnoxious in other whales. When not pursued, the whales would “sound” from 3 to 6 minutes and frequently swim right alongside one another tail to tail. Occasionally the enormous head, which forms about one-quarter of the body, was pushed vertically out of the water to a height of about 8 to 10 feet. At other times a whale would “bask” motionless at the surface in the manner of swordfish.

To come within a few feet of a whale does not happen to many people nowadays, if one disregards the visitors to aquaria where porpoises are kept. Even the barnacles and parasites on the heads of the right whales could clearly be seen. The opportunity of a lifetime, and William E. Schevill, the man in charge of whale sound recording, was 3,000 miles away. However, he is satisfied that the sounds were recorded - thanks to Captain Poole’s initiative - and now form a part of the ever growing collection of sounds made by whales, fishes, and other marine animals kept on file at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Comments