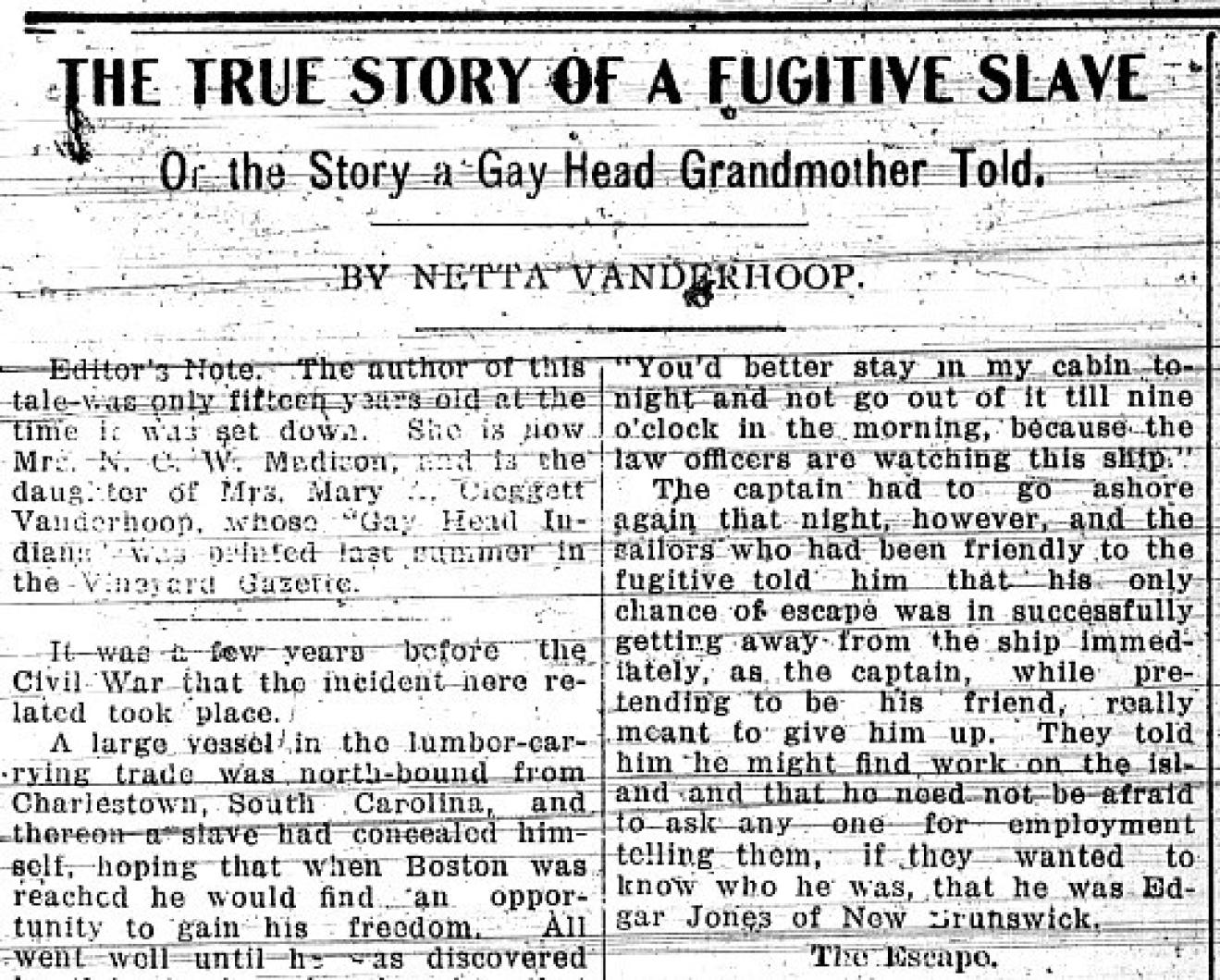

Editor's note: The author of this tale was only fifteen years old at the time it was set down. She is now Mrs. N. C. W. Madison, and is the daughter of Mrs. Mary Vanderhoop.

It was a few years before the Civil War that the incident here related took place.

A large vessel in the lumbor-carrying trade was north-bound from Charlestown, South Carolina, and thereon a slave had concealed himself, hoping that when Boston was reached he would find an opportunity to gain his freedom. All went well until he was discovered by the captain, who thought that perhaps some of the ship's crew had guilty knowledge of his concealment or had even gone so far as to assist him in making his escape from a land of ceaseless toil, where there was naught for him but the lash, the slave-pen and the bloodhound.

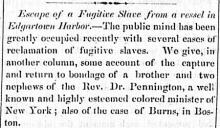

The laws of those days were so rigid that men generally neither dared nor cared to assist escaping slaves, and the captain reluctantly decided that the best thing he could do was to go into the first port, tell his story and give up the slave. Accordingly he anchored at Vineyard Haven and immediately sought the custom house officers and the sheriff. The latter said he would come after the runaway at nine o'clock the next morning. When the captain went aboard the ship that night he said to the slave, whose name was Edgar Jones, “You'd better stay in my cabin tonight and not go out of it till nine o'clock in the morning, because the law officers are watching this ship.”

The captain had to go ashore again that night, however, and the sailors who had been friendly to the fugitive told him that his only chance of escape was in successfully getting away from the ship immediately, as the captain, while pretending to be his friend, really meant to give him up. They told him he might find work on the island and that he need not be afraid to ask any one for employment telling them, if they wanted to know who he was, that he was Edgar Jones of New Brunswick.

The Escape

At eleven o'clock that night slave stole quietly out of the cabin, softly and quickly, lowered a boat and silently rowed away. He landed at East Chop, near Vineyard Haven harbor, and drew the boat high on the beach. For three days he hid in the woods and cornfields, living on raw corn. At the end of the second day he went to see if the boat was still safe, because he did not want the captain to lose it. He asked three men for work, but they all said they had help enough, and in reply to his further queries concerning employment one of the men told him to go to Gay Head and the people there might give him work. So he came up the Island and stayed for nearly a week at Mr. Moses Bassett's, working for his food and lodging. No one knew he was a slave, for the poor fellow, not knowing he was among friends, kept his secret to himself as the sailors had told him to do so.

Early one morning, just as the postmaster of Gay Head, Mr. William Vanderhoop, was finishing his breakfast, the sheriff rode up and asked him if he would help him catch a man who had run away from a ship, adding that he would pay him ten dollars for his trouble. Mr. Vanderhoop was preparing to go to Vineyard Haven with a load of cranberries for market, and did not propose to put off his trip for ten dollars. But Mrs. Vanderhoop had overheard the conversation. She suspected that something was wrong, for it did not seem quite probable that the sheriff was offering so much as that to catch a common sailor. Just as the sheriff was leaving she carelessly inquired where the vessel was from.

He evasively replied, "From the South," stating no particular place. Mrs. Vanderhoop's suspicions were increased rather than allayed, but she said nothing, and the sheriff and her husband departed, their destinations lying somewhat in the same direction.

In the meantime, in another part of Gay Head, Mr. Bassett, his brother and the stranger were just about to sit down to breakfast, when the latter, who was none other than the slave Edgar Jones, suddenly jumped as if shot and sprang out of the door opposite the window from which he had been looking, disappearing in the thick swamp back of the house. Mr. Bassett looked out to see what was the matter and was surprised to see the sheriff.

"A dollar for each of you if you will help me catch that man," cried the officer. They followed him, but they did not catch him.

Mrs. Vanderhoop had been thinking all the morning. "I wonder if that poor fellow the sheriff is after is a slave," she said to herself as she kept glancing out of the door.

Suddenly she heard shouts, and hurrying to the door she saw a man coming over the hill, running as fast as he could. He was desperately endeavoring to escape several pursuers. Snatching up a shawl she ran swiftly toward the place where she saw the men, for now she was sure that it was a slave they pursued.

Mrs. Vanderhoop to the Rescue

The men had outrun the sheriff, and when Mrs. Vanderhoop reached the spot where they were that official was nowhere in sight. She told the young men that the man they were chasing was probably the slave, and begged them not to help catch him. They gladly yielded to her wishes and were very indignant with the sheriff for using a pretext in his attempt to make them slave-catchers.

When he came up they at first said they did not know where the man was, but that he was last seen running over a near-by hill. They then told him that they knew, but were neither going to tell him or render any further assistance. The sheriff then asked a little boy who was standing near if he had seen a man run past there. The youngster, innocently enough, pointed to the place in the bushes where the slave lay hidden. The sheriff saw him but did not dare attack him alone, so a watch was stationed in the tower of the lighthouse while he went to get his sons to help him effect the capture.

After the sheriff had gone for help Mrs. Vanderhoop went back home to find a customer in the village store which her husband kept. To this lady she told the story and then asked: "Do you think that man would hurt me if I went there and tried to get him to come out and hide in my house?" The lady said she did not think he would. Mrs. Vanderhoop went up stairs and quickly secured an old dress and bonnet, and returned to the place, quietly calling:

"If you hear me, answer, but do not rise up. Answer, for we want to help you before the sheriff gets back with men enough to take you."

Suddenly she heard a rustling sound close to where she stood and it frightened her very much. Then the slave rose on his hands and knees right beside her and said, "Here me be."

She quickly recovered from her fright and said to him: "Put on these things at once and come with me. Walk on my right side with your head bent forward and do not turn in either way." The fugitive obeyed the kindest mistress he had ever had and step by step approached his freedom.

The Slave's Story

The men in the light-house saw what they thought to be two women going over the hill to the post-office. There was nothing strange in that. On reaching home Mrs. Vanderhoop hid the slave in the garret. There she fed him, and while he ate he told her his story. In brief it was this:

He had tried once before to run away but was captured and carried back to his master, who was very cruel. He was beaten until the blood ran and then dragged down three flights of stairs, his master threatening that his bloodhounds should feast upon him if he ever ran away again. He knew that his master would keep his word, but this did not daunt him and he ran away a second time with forty-one other slaves. All but two (Edgar and one other) were captured. Once when the men were searching the swamp where the two were hiding, the hounds came so close to him that he was compelled to run into an old lake full of dead leaves, mud and water. Here he lat down and pulled the dead leaves over his head to keep from being seen. In this way he succeeded in throwing the dogs off the scent.

After a few days the men gave up hunting in that swamp, and when he was sure they had gone he came out. He fed on berries and whatever else he could find in the woods that would stay his hunger. After that, day after day, he went out on the high hill back of Charleston, to see if he could see any ships coming into the harbor.

He had had a dream and something had told him that it would come true. He had dreamed of seeing a large ship come into the harbor for lumber and it had seemed to him that he was to go down there and the sailors would let him go with them to the North. One day as he was watching on the hill he saw a ship come in that looked exactly like the one he had seen in his dream, and as soon as she dropped anchor he went down to investigate. The sailors told him that the ship was northward bound and said that if he would come down that day they would hide him under the lumber in some way. He decided to try the plan, for he had resolved when he ran away the second time that he would never be taken back alive, but instead would die fighting for his freedom. Such was the story he told Mrs. Vanderhoop while hiding in her garret.

By the time the sheriff returned with his men the whole reservation (Gay Head was not a town then) was aroused by this man-hunt in the North. Ninety-nine per cent of the men were determined that the slave should not be taken. Just here another difficulty confronted the sheriff. He must have warrants before he could search houses, and it would take no less than six hours to get them.

Escape to New Bedford

Certain arrangements were hurriedly but effectually made. Midnight was set for the time when Mr. Samuel Peters should take his sailboat and carry the slave to New Bedford, for the people of Gay Head knew that if he once reached there he would be perfectly safe. On the shore there gathered a large number of men, armed with guns, pitchforks, clubs, and almost anything that would do to fight with. In case the sheriff came with armed men and demanded the slave's release these me had made up their minds to resist him to the end, even though they had to kill or be killed. In some way the sheriff got wind of the true state of affairs and failed to put in an appearance.

The boat got away safely and Mr. Peters and his charge reached New Bedford at seven o'clock the next morning. There Edgar Jones remained for some time, working about the wharves. Everybody liked him, and at times when some of the help was dismissed because business was dull, he was kept at work, for his employers highly valued his services.

Sometimes he came back to see Mrs. Vanderhoop. He called her Mother, brought her money, and said he loved her very much. Just before the war broke out he went to San Francisco and has never been heard from since, though many think he went to the war and was killed. Thus ends a true story of the ante-bellum days, and for years thereafter people used to come and shake the hand of brave Beulah Salisbury Vanderhoop and thank her for the womanly part she had played.

Comments