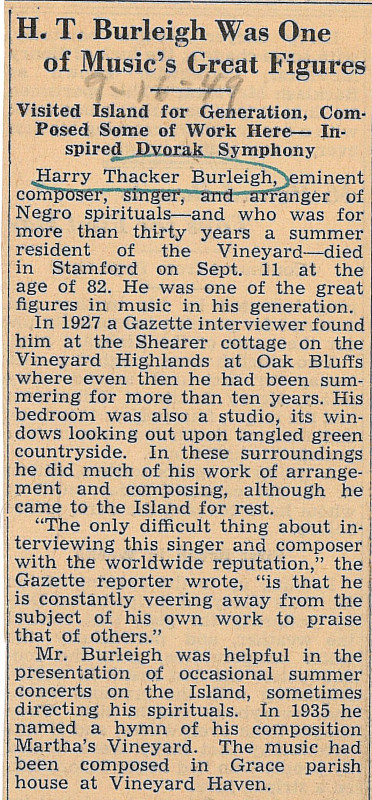

Visited Island for Generation, Composed Some of Work Here — Inspired Dvorak Symphony

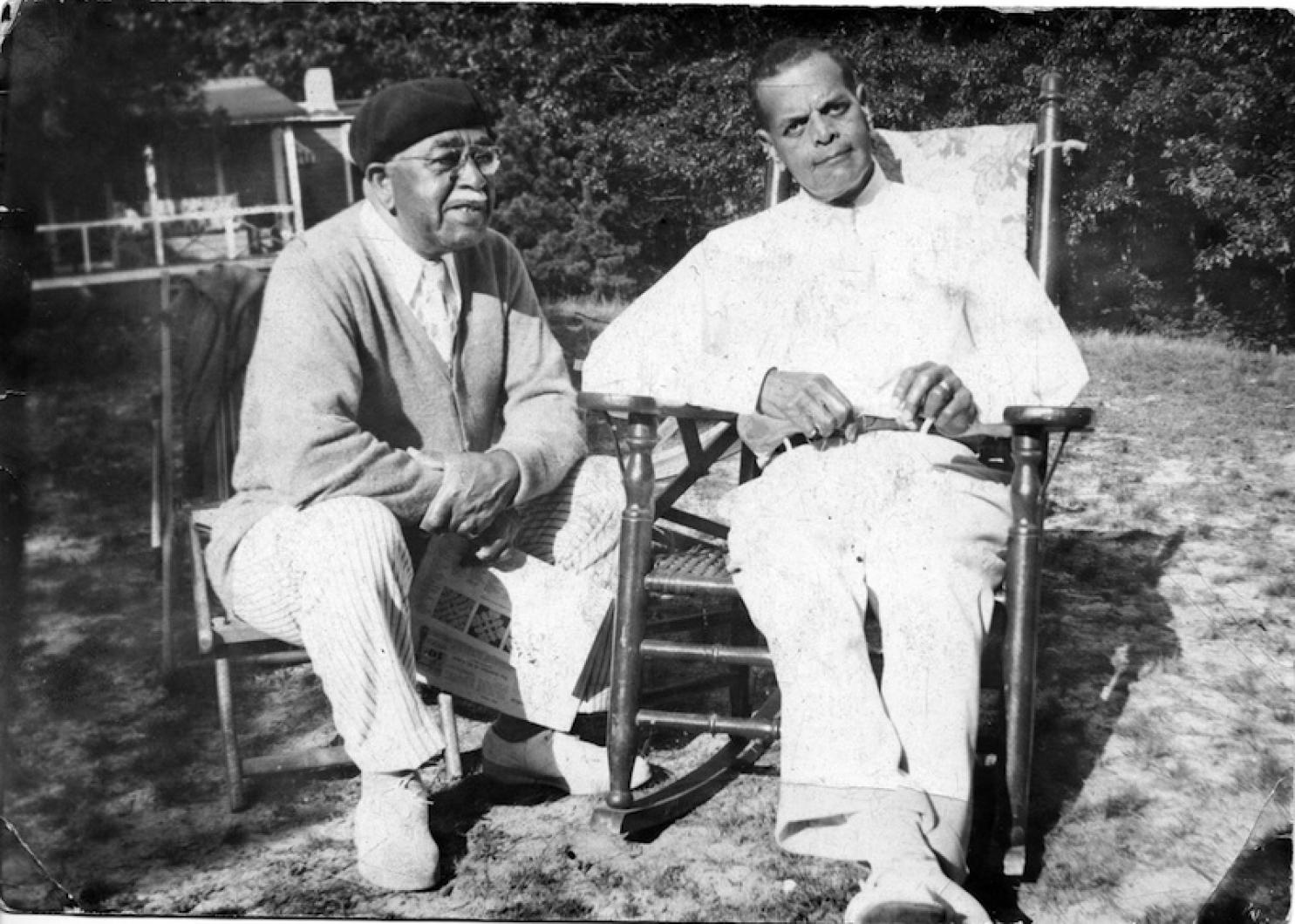

Harry Thacker Burleigh, eminent composer, singer, and arranger of Negro spirituals — and who was for more than thirty years a summer resident of the Vineyard — died in Stamford on Sept. 11 at the age of 82. He was one of the great figures in music in his generation.

In 1927 a Gazette interviewer found him at the Shearer cottage on the Vineyard Highlands at Oak Bluffs where even then he had been summering for more than ten years. His bedroom was also a studio, its windows looking out upon tangled green countryside. In these surroundings he did much of his work of arrangement and composing, although he came to the Island for rest.

“The only difficult thing about interviewing this singer and composer with the worldwide reputation,” the Gazette reporter wrote, “is that he is constantly veering away from the subject of his own work to praise that of others.”

Mr. Burleigh was helpful in the presentation of occasional summer concerts on the Island, sometimes directing his spirituals. In 1935 he named a hymn of his composition Martha’s Vineyard. The music had been composed in Grace parish house at Vineyard Haven.

After 52 Years

Mr. Burleigh retired from the choir of St. George’s Protestant Episcopal Church in New York in 1946 after fifty-two years as baritone soloist. His death occurred in a convalescent home where he had been cared for for the past two years.

Mr. Burleigh’s life was one continuing flow of music; creative, imaginative, and almost always touched with the beauty and emotional power of the Negro spirituals. Music helped to design for Mr. Burleigh personally an existence that knew a full share of fulfillment. But the music that he made as a composer and singer was even more important in what it did for others.

He was the arranger of at least fifty Negro spirituals. One of these was the popular Deep River. He wrote more than 100 songs, the most famous being Little Mother of Mine, which John McCormack sang in concerts throughout the world.

He was one of the most famous church singers in New York city. On each Palm Sunday for fifty-two, consecutive years, from 1894 until he retired in 1946, Mr. Burleigh sang The Palms by Faure at the morning and vesper services at St. George’s church. In later years the Palm Sunday solo at St. George’s became almost a city tradition and was frequently reported in the newspapers.

The stories always told of the tears that filled the eyes of many in the congregation when Mr. Burleigh, a distinguished-looking man with white hair and a dapper white mustache, stepped briskly down from his place in the rear of the scarlet-clad choir and sang the anthem.

Mr. Burleigh gave invaluable service in the work to preserve the Ngro spirituals. He not only was a pioneer in singing spirituals on the concert stage, but he was among the first to set down on paper the Negro folk songs, which, until that time, had been handed down orally. There was some opinion that without his work the spirituals might have been lost because many Negroes wanted to forget them and the conditions out of which they grew.

Sang at Home and School

Born of poor parents in Erie, Pa., he always sang; he sang while he helped his mother at home, or as he polished desks in a school where his mother was the janitor. He was a lamp lighter for a time, singing at his work, even at 4 a. m., when he moved from pole to pole snuffing out the lights. He sold newspapers, was an elevator operator, a pantryman on a lake steamer, and a wine boy at the Grand Union Hotel, Saratoga, N. Y., where he sang for the late Victor Herbert.

In 1892 Mr. Burleigh won a scholarship to the National Conservatory of Music in New York, where he was befriended by Mrs. Frances Knapp MacDowell, mother of the late Edward MacDowell, the composer, and where one of his teachers and friends was the late Antonin Dvorak, the composer of the New World Symphony.

Dvorak was fascinated by Negro spirituals, and had Mr. Burleigh sing them for him over and over again, particularly after supper when the Czech composer was tired. He used the Negro spiritual theme for the largo movement in his New World Symphony in 1893, and it was generally conceded that Mr. Burleigh inspired the work. This was believed to be the first time a Negro’s song had been a major theme in a great symphonic work.

In 1894 Mr. Burleigh was the only Negro among sixty men who applied for a vacancy for a baritone at St. George’s church. He won it. The elder J. P. Morgan, for many years senior warden of the parish, had Mr. Burleigh sing at his home every Christmas. From 1900 to 1925 he also sang in the choir of Temple Emanuel, the only Negro to have sung in the choir of the synagogue. He made concert tours here and abroad, singing for the late President Theodore Roosevelt, the Archbishop of Canterbury, the late Ignace Jan Paderewski, and in 1908 did two command performances for the late King Edward VII.

Beginning in 1923, an annual service of Negro spirituals was held at St. George’s, with arrangements and harmornzations by Mr. Burleigh, who could sing in English, Hebrew, Latin, French, German and Italian.

Among the spirituals Mr. Burleigh arranged were Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen, Couldn’t Hear Nobody Pray, Let Us Cheer the Weary Traveler, Were You There?, and Everytime I Feel de Spirit.

He composed the music for the late Rupert Brooke’s The Soldier, Walt Whitman’s Ethiopia Saluting the Colors, and The Young Warrior, by the late James Weldon Johnson. He did the settings for The Five Songs of Laurence Hope. He was a charter member of the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers.

Surviving is a son, Major Alston Burleigh, comporser and choral arranger, and a grandson, Harry T. Burleigh 2nd. He lay in state at St. George’s church until the funeral services were held there at 8:30 p. m. Thursday.

Comments