She was christened by the eight-year-old daughter of Jimmy Cagney. A truckload of 200 live quail once opened up her freight deck (“They were pulling them out of the rafters,” Donna Honig of Edgartown said of the crewmen that trip in 1991. “They were diving after them”). And once on a night back in the fall of 1972, an assassination nearly took place on her darkened hurricane deck when a man, angered by Robert S. McNamara’s role in the Viet Nam war, tried to throw the former Secretary of Defense over the side.

To these events, add one more that will happen at the end of this month:

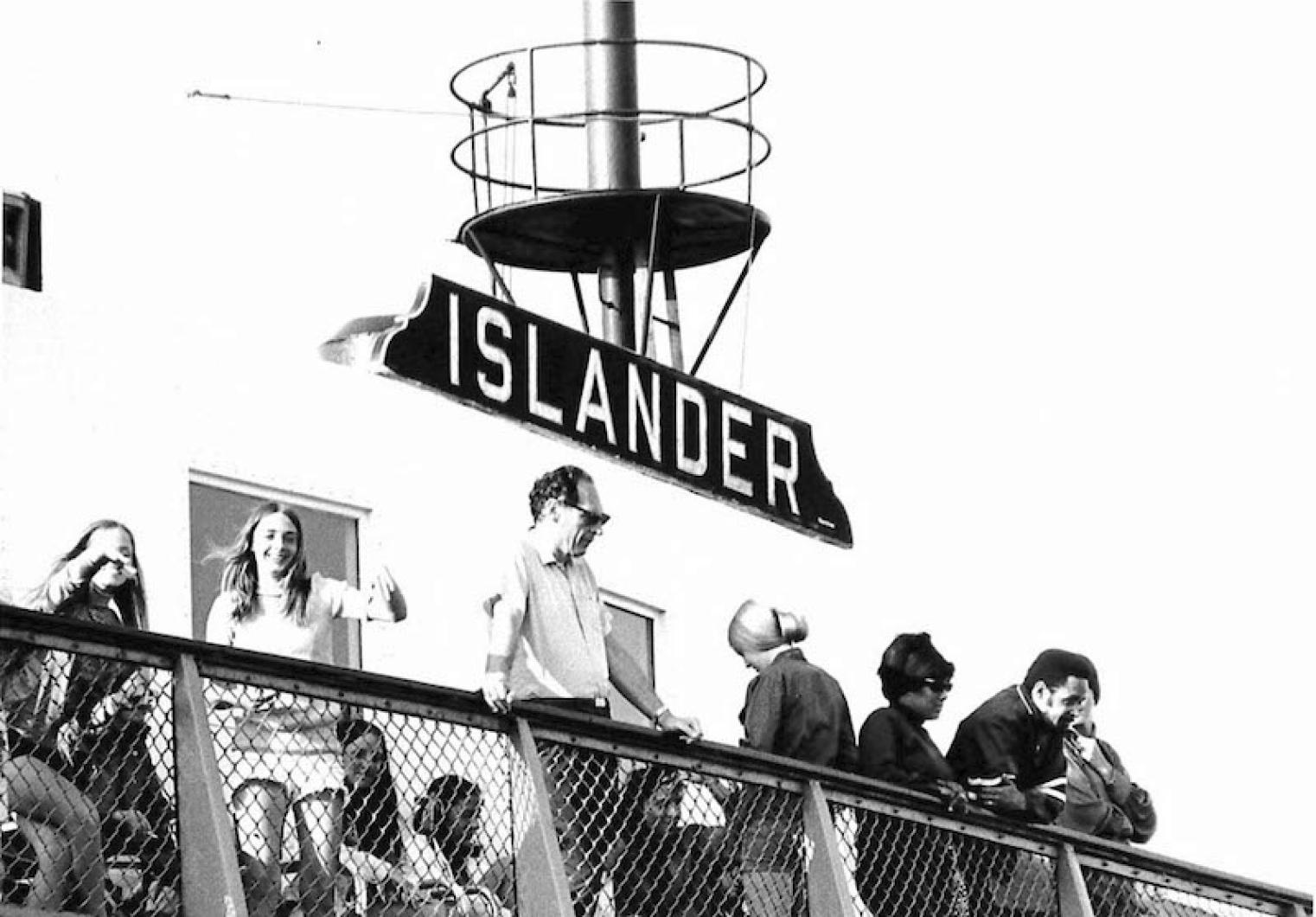

With her first trip from Vineyard Haven on the morning of Oct. 28, the Islander breaks the record for length of service by any Island steamer or ferry. No ship of iron or steel - and almost certainly no vessel of wood or sail - has ever carried freight, human or otherwise, to and from the Islands for as many days as will have the Islander with her departure from the Vineyard at sunrise on that Wednesday morning.

That day the Islander will start her 17,696th day of service, beating the record of the retired steamship Nobska by one day. Since the Steamship Authority does not contemplate replacing the Islander before 2005, it is almost certain that she will cross the threshold of her 50th year in the spring of 2000, and by the end of her life add tens of thousands of miles to the more than one million she has sailed already, almost every one of them on the short course of a left turn, a straightaway and a right turn between Vineyard Haven and Woods Hole.

In that lifetime, the Islander has endured groundings, collisions and crashes into her slip that would have disabled and - on one occasion - perhaps even wrecked any of her more lightly built sisters of the present day. In 1980 she ran over an uncharted rock during an unusual springtime assignment to Oak Bluffs and came within a few minutes of foundering before her captain and crew wrestled her back into her dock, with her rudder and prop lifting out of the water and her forward two compartments (out of eight) filling with 15 feet of water.

But the real story of the Islander and the people who have sailed her, as she shoulders up to the record for length of service this month, is one of awesome reliability and what looks like routine. For every year made noteworthy by an accident, a decade has passed without one. Assuming an average of just a quarter-load per trip over the length of her life, she has carried more than 33 million people without serious injury and more than four million cars without damage from her maiden voyage on May 18, 1950, to the trip she’s making as you read this.

Which brings us to the math and how the Gazette did the counting:

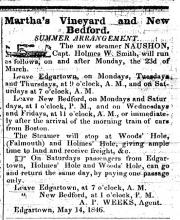

We started with the maiden voyages of both the Nobska (April 9, 1925) and Islander (May 18, 1950) and ended with the last day of service of the old steamer (Sept. 18, 1973). We counted days in layup or rebuilding as days of service for both vessels - and yes, we counted leap years. The Nobska, a steamboat whose line swept downward from a upright stem to a fantail that barely scudded over the surface, and whose wailing whistle cried out from a single tall stack amidships, sailed between the mainland and the Islands for 48 years, five months and a little more than a week, or 17,695 days. Add one day to that stretch, and the Islander claims the record on the 28th.

(A small asterisk here: The Nobska, hurriedly replacing a steamer that had burned the year before, arrived that spring and after final fitting out in New Bedford went into service without fanfare on April 9, 1925. The Islander made her maiden voyage to Vineyard Haven for a dedication ceremony - which more than 3,400 Islanders attended - on May 18, 1950, and actually went to work on Saturday, May 20.)

From that first voyage, in which she was feted by the Vineyard Haven Band and a service at the Seaman’s Bethel (and during which she carried her first car across the Vineyard Sound, a sedan of unknown make belonging to Albert Haas, a Steamship Authority consultant), to those she is making today, the Islander has become more than just a symbol of the Vineyard; she is now an extension of it.

For generations, Vineyarders and visitors driving down the Woods Hole Road have looked ahead over the crest of the parking lot to see the rounded bow and black spear painted along the side of the Islander and considered themselves already home; at this end, Vineyard Haven harbor without the Islander in her slip looks somehow incomplete. With the end of her service not far ahead, it is worth noting that she has carried Island passengers who were born in 1870, and those who will be alive in 2070.

The story of the Islander stretches back over five decades, four wars, three generations, two steamship companies and an epoch in the life of Martha’s Vineyard. It is fair to say that her arrival that spring morning in 1950 finished up the long, slow introduction of this Island to the 20th century.

It was an introduction that began with the arrival of her ancestors, the first really large and muscular propeller-driven steamers, in the 1920s. It deepened with the Depression, when the Vineyard found itself increasingly bound to federal assistance and federal ways of doing things. And it was nearly sealed by the arrival of thousands of servicemen from all over the country who discovered the Island while training at the new naval air station - now the county airport - and who would soon return for holidays with their families after the war on this brand new, double-ended superferry, then the largest in New England.

Before her, not a single tractor-trailer truck had ever been carried to the Island of Martha’s Vineyard by anything other than a specially consigned barge. No ship had ever ferried more than 35 cars a trip. None had reliably made seven round trips a day. For good and for ill, the Islander was part ferry and part seagoing bridge. She has won the love of the Vineyard not for beauty or comfort, as her predecessors did, but for a devotion to duty that none of them have ever matched.

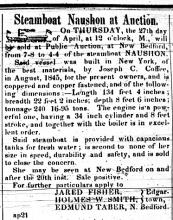

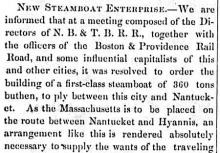

She was the first undertaking of what was then the New Bedford, Woods Hole, Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket Steamship Authority. The new state agency, trying to organize itself after the failure of a private company that had briefly run the Island boats after World War II, began to talk about a new ferry for the Vineyard route in May 1949, when the Authority was just one month old and carrying a terrible leftover debt.

That the Vineyard embraced the idea of the Islander underscored just how much things had changed on the Island in the three years of prosperity following the war.

Early in 1946, the Massachusetts Steamship Lines had tried to sell the Vineyard on the concept of real ferry service, but the Island recoiled before the gothic image of the former Hudson River ferry Hackensack that appeared in the paper that winter. Slung low to the water, with a yawning, ungated maw at either end, it looked as if the seas of Vineyard Sound would roll down her deck, sweeping cars three or five at a time off the stern and into her wash.

The tides played with her some, and the chip did wet her down plenty, but like the recently adopted Coast Guard ferry Governor - another open-decked vessel and veteran of service in New York harbor - the replanked and renamed Islander did all right during her brief term of service, well enough to convince the Vineyard that ferries saved time and got to the point, which was getting people here with as many cars as they wanted.

But the hull, the propulsion, the breadth and the purpose of this new ferry were entirely new concepts to an entirely new boat line. Nothing remotely like her had ever sailed here before. “There are some difficulties that will always haunt the Authority. Nantucket Sound is not an ideal place to run a steamship line,” said the annual report for the Steamship Authority in 1960, and it went on to describe those challenges neatly:

“There are many shoals, the Sound is open to stiff gales of wind, and it is subject to fog because it is only some 50 miles west of the Gulf Stream....The entrance to Nantucket harbor is supposed to be dredged out to a depth of 15 feet; it is constantly filling up, and in places it is probably about 13 feet. The design of the vessels we use is largely determined by this shallow estuary.”

Eads Johnson, a prominent New York naval architect, was chose to design the ferry, with the assistance of Capt. Winthrop D. Hodges, port captain and general manager for the new boat line. The idea would be to build a wide hull that drew little water, stow the passengers in spartan alleyways down the sides, give her as much power as possible and have faith that she could bust her way through almost anything the North Atlantic might throw at her.

The contract for the new ferry was awarded in October 1949 to the Maryland Drydock Company in Baltimore, which had bid $687,510 - equivalent to about $4,675,000 today, and almost exactly half what the straitened Authority had budgeted. Thus the boat line might have ordered two Islanders that fall, but it decided to save the cash. The keel was laid a month later, and with the hull lying upside down, construction began.

At 200 feet, 6 inches, she would be nowhere near the longest vessel to serve the Islands (indeed, the Nobska and her three sisters of 25 years before were all longer), now with so much volume devoted to cars and trucks would she carry a great load of passengers (just 682 in summer, when most of them could survive awhile in the water if they wound up there, and 142 in winter, when her four lifeboats would have to carry everyone in an emergency). Her beam was 60 feet, her draft when fully loaded just 10 feet, 6 inches, allowing her to cross that shallow bar at the entrance to Nantucket harbor - which the Islander did for a few winters in the 1970s. Her tonnage was rated at 2,060.

The ferry was to be driven by a Fairbanks Morse eight-cylinder, slow-speed, 1,600 horse-power direct reversible diesel engine, the first diesel plant specifically built for the Island line. “It’s simplicity we’re after,” said Steven Carey Luce, the most prominent businessman on the Island and secretary to the new Steamship Authority. One propeller of four blades and measuring seven feet, four inches was mounted at either end. Fully loaded, she was designed to sail at 11 miles an hour.

The new vessel as yet had no name, so the Gazette asked readers to come up with one. The list ranged from the tenable (Islander, Governor Mayhew, Island Queen) to the untenable (Katharine Cornell, Enterprise, Heavenly Isle) to the unimaginable (My Dream, Our Wish, Pride of the Sea, Lady from Falmouth, Duchess of Tisbury, Bermuda of the North, Queen Martha, Lady Martha, Martha’s Islander, Merrylander, plus a bunch of pastiche neologisms such as New-Mar-Nan and Ma-Wo-Na-Va).

The Steamship Authority went with Islander.

It also made the astonishing decision to christen her with a champagne bottle from a shipwreck - and not just any shipwreck, but the worst in the history of southern New England, a grounding that resulted in 103 deaths almost beneath the Gay Head Cliffs. On a night of shrieking winds on Jan. 17, 1884, the coastal steamer City of Columbus, sailing from Boston down to Savannah, ran up on the rocks of Devil’s Bridge and sank while most of her passengers and crew slept in their beds. Only 28 survived the disaster; not one was a woman or child.

The bottle was part of a case salvaged by an Island shipmaster and donated to the event by Henry Cronig of Vineyard Haven. The job was given to Cathleen Cagney, the eight-year-old daughter of actor and summer resident James Cagney, and on the morning of Feb. 21, 1950, she smashed the old bottle against the Islander’s bow, which still had no superstructure. Some hours later she would thrust her hands into the face of a Gazette reporter and, noting the residue of alcohol still upon them, command, “Here, smell!”

The Steamship Authority, as well as Gazette librarian Eulalie Regan and Michael J. Slater, a Vineyard visitor from Cranborne, England, and Calgary, Alberta, helped with the research of this story. Part Two will appear next Friday.

1 comment

1 comment

Comments (1)

Comments