She was, quite simply, enormous.

On those mornings or afternoons when she sailed past her older sister ship, it was possible to stand on the uppermost deck of the new steamship Islander and look down on the roof of the pilothouse of the sidewheeler Uncatena.

Though only 21 years separated the launching of this last sidewheeler from this newest propeller ship, the Uncatena belonged technologically to the middle of the 19th century, the Islander to the latest advances of the 20th. The engine of the Islander, driven by four cylinders, delivered twice as much horsepower to a single propeller as the walking beam plant delivered to the two sidewheels of the Uncatena. Even though she carried far more freight, the Islander drove through the water just as fast as the Uncatena - and on days of heavy weather, much faster.

What was so impressive about all this power and grace was that the Islander, just 25 feet longer than her older sister, could carry at least twice the number of passengers and four times the number of cars. There has never been, before or since, such an instantaneous leap upward in passenger and freight capacity on any Island line. Imagine a new ferry rounding West Chop on her maiden voyage today with the ability to carry 240 cars and nearly 3,000 passengers. That’s the scale of what happened when the Islander began service in 1923.

When the Islander sailed to Martha’s Vineyard from New Bedford for the first time on August 9 of that year - without ceremony, her ensign at half-mast to honor the death of President Warren G. Harding seven days before - her size, strength and speed did nothing less than usher the Vineyard into the 20th century.

Before her, sidewheelers built for Island service had been designed by homegrown companies with passengers in mind, first and last. The Gay Head of 1891 had a 50-foot social hall “laid out with black walnut and maple,” a Neapolitan interior “finished ornately in gold trim” and cherry wood seats “covered with maroon plush velvet upholstering,” according to The Island Steamers, a definitive history by Paul C. Morris and Joseph F. Morin.

To be sure, the Islander had long, clean, handsome lines and was, by the standards of an epoch yet to come, more than merely accommodating. Her interior spaces were airy, her slatted wooden benches comfortable, her day cabins serviceably furnished with couch, folding card table, two chairs and a sink. But what the Islander was really built to carry was the car. The sidewheelers, never anticipating the automobile, managed after the turn of the century to stow six or seven at a time in an unsheltered wedge at the bow. The covered freight deck of the Islander ran two-thirds the length of the 210-foot ship.

The Islander could carry 30 cars per trip. She made four round-trips a day in season. She was the first of four vessels built in less than seven years - this was another record, the most ambitious shipbuilding program of any boat line in Island history - and although all four boats were built along the same general lines, each was able to carry a few more cars and passengers than the one before. The last of the four sisters in what came to be known as the great white fleet was the Naushon, at 250 feet the largest ship ever to sail regularly to the Vineyard and Nantucket.

Little wonder that the 1920s was also the most ambitious road building and paving decade in Island history.

Little wonder, too, that these four ships changed the lives of Islanders, and the ways of Martha’s Vineyard, forever. Not only could these vessels move a tremendous number of cars and people back and forth across Nantucket Sound - at the peak of each season, bringing mainlanders to the Island and Islanders to the mainland by the hundreds and thousands every trip - they could make the voyage almost any day, wind, sea and tide notwithstanding. With hulls of steel and the propulsion system sheltered at the stern rather than exposed along the sides, they could cut through ice and manage all but the most mountainous seas. Before the Islander, the people of Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket expected the possibility - perhaps even the probability in nasty weather - that they might not be able to make a trip across the Sound on any given day. After the Islander, they expected to be able to make the trip at will.

Designing a ship such as the Islander looks like a fairly simple matter. By 1923, steamboat companies were building and running vessels like her up and down both coasts. But the two New Englanders who worked out the design - Albert F. Haas and William T. Berry, men who knew the nature of these waters and worked for the New England Steamship Co., the firm that ran the ships Ñ faced a peculiar and daunting challenge: the shoals at the entrance to Nantucket harbor.

The bar, as it was known, had doomed the growth and finally the existence of Nantucket’s whaling fleet a century before, because ships returning home heavily freighted with oil and bone could not clear the shoals at the entrance to the harbor. Now the bar limited modern steamers to a draft of 10 feet - which also, due to shipbuilding formulas, affected length and beam. The designers gave the hulls as much breadth as they could, making all four ships, best known by the names they carried most of their lives (Martha’s Vineyard, Nobska, New Bedford and Naushon), phenomenally good sea boats in just about any weather.

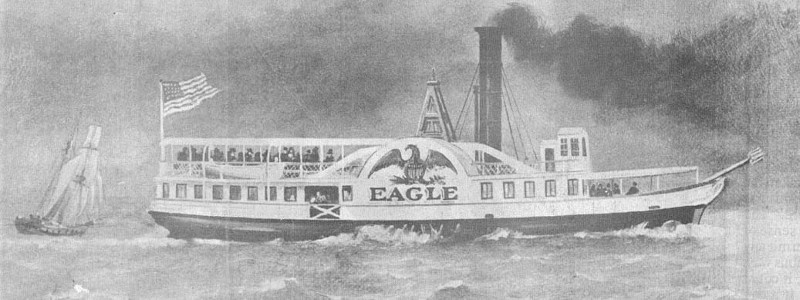

The subject of safety on the Island line is easily overlooked because the record is so extraordinary. It is estimated that one-quarter of all the ships lost along the Atlantic coast after the arrival of the English were wrecked between Gay Head and the tip of Cape Cod. But although there have been a few fatalities as a result of isolated accidents aboard Island boats going back to the first steamer ever to make the trip from New Bedford Ñ the tiny 80-ton sidewheeler Eagle of 1818 Ñ no one has ever died as a result of a collision, fire, grounding or other disaster. This is remarkable, given the shallow water around the Islands, the often perilous and unforgiving weather and the fact that no boat had a radio before 1933 or radar before the end of World War II.

The New England Steamship Co. operated these revolutionary vessels, but it was the New Haven Railroad that had made them possible.

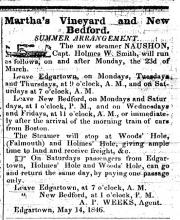

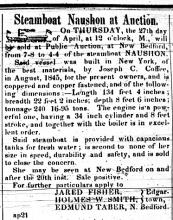

Trains began to run down to Woods Hole from Boston in 1872, managed by the Old Colony Line. This branch and its best known train, the Flying Dude, would quickly become known as the most famous resort line in all of New England. The New Haven Railroad took over the Old Colony in 1893 and, concerned about rivalry from steamboats along the coast, began quietly acquiring shares in the newly consolidated New Bedford, Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket Steamboat Co. In 1911 the railroad assumed total control of the Island line. With railroad management came the capital to design and build the great white fleet, and with ships of such size, beauty and power, it looked as though the Islands might not want for anything more in the way of transportation across the water for as far into the future as anyone could see.

Then came World War II.

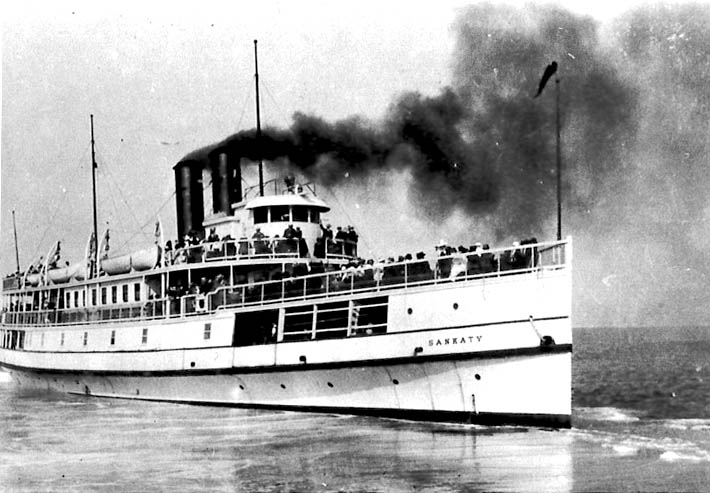

If the Islands had never before seen such an ambitious scheme of ship construction as they did in the 1920s, neither had they ever experienced such losses as they did in 1942. Once before, in 1924, an Island steamer had burned overnight in New Bedford. The destruction of the Sankaty had caused the New England Steamship Co. to see what it lacked in terms of the size and design of its Island ships, and inspired it to embark on the building of the white fleet. Now, in the summer of 1942, the Islands would lose their two largest boats in the space of just a few weeks. The government requisitioned them for service in Europe as hospital ships.

“Where she goes, something of the Vineyard must go too,” said the Vineyard Gazette when the first and largest of the two vessels, the Naushon, was taken early in July. “Between the Islands and their boats there is a tie like that which binds families and lifelong friends. It is never broken. Wherever the Naushon may steam on her new business of war, she is still our boat.”

The trip across the Atlantic was a harrowing one, particularly for the New Bedford. When the steamers Boston and New York were torpedoed and sunk roughly halfway across the ocean, the New Bedford Ñ the smallest ship in the fleet Ñ was ordered to stay behind to pick up survivors. A submarine launched a torpedo at the New Bedford herself, but the sub captain apparently misjudged her shallow draft and set the depth too low, for the New Bedford was able to rescue as many men as she could find, scatter with the rest of the convoy and make England safely.

Both ships would serve the Allies along the shores of France on D-Day; one Vineyarder, Everett S. Allen, later wrote of seeing the Naushon from the beach, “a bright bone in her teeth, threading her way through the fleet and bound inshore. She had come to Omaha Beach in Normandy to take back the first wounded to England. Her lines were unmistakable as she stood in, and it just happened that she was starboard side to [the beach] and turning, exactly as I used to see her day after day as she rounded the breakwater at Vineyard Haven with a long and two shorts of the whoomping whistle to let everybody know she was coming.”

Vineyarders hoped that after the war these two faithful sister ships would return to the Islands for which they were built, but most knew better. They sensed a new kind of boat would be needed. They didn’t know they would need a new kind of boat line to go with it.

In 1930 the New Haven Railroad owned 129 vessels, including the breathtakingly beautiful steamers running day and night between New York and Fall River. The Fall River Line collapsed during a strike in 1937, and with the loss of this flagship company, the New Haven Railroad, itself in financial trouble, began to turn away from steamboating. At the end of the war, the only two ships the company still owned were the Martha’s Vineyard and Nobska, then known as the Nantucket. On Dec. 31, 1945, the railroad sold the New England Steamship Co. to a makeshift and undercapitalized firm called the Massachusetts Steamship Lines.

In its brief life, the new company did one significant thing: It introduced modern double-ended ferry service to Martha’s Vineyard. Lying cold and gloomy on the Hudson River was the Hackensack, a low-slung, gothic-looking craft, built in 1901. The Massachusetts Steamship Lines bought this boat, hurriedly sheathed her in new wood, painted her aluminum, left the bow and stern wide open to sea and sky, renamed her Islander and sent the old river girl out into the breaking seas between West Chop and Nobska Point. That she endured this torture for three years without spearing her way into a wave and never emerging again on the other side is one of the minor miracles of Vineyard Sound.

On the Fourth of July weekend of 1946, reported the Gazette, after the Hack blew something vital deep within her innards, there developed in Woods Hole “the greatest jam of Island-bound automobiles in history” - meaning as many as 80 cars, one of the first standby lines ever, with drivers paying crewmen bribes of up to $25 to get their cars across with the owner behind the wheel.

When the Hack was condemned in 1948, so was the rickety boat line that owned her. But it was clear from this awkward little experiment that ferries were now the only way to go.

The economic boom, the coming of the interstate highway system - these postwar facts of life did indeed demand new boats, and a new boat line that would guarantee year-round service to Islanders regardless of profitability. In 1949, out of the fragments of the failed Massachusetts Steamship Lines, the state created the New Bedford, Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket Steamship Authority. Each Island or mainland town served by the new boat line appointed one person to the governing board (in those days the governor made an appointment too), and any deficit was paid by yearly and proportional assessments to the places it served.

If the steamer Islander introduced the Vineyard to the first half of the 20th century, then the third and newest ferry Islander, built specifically for Vineyard service, introduced it to the second half. The Islander - still at work today, now the longest-serving boat in the history of Island commerce - made her maiden voyage on May 18, 1950. The Islander was the first capital endeavor of the new Authority, and it is hard to underestimate what the new ferry did for, and to, the Islands of Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket beginning with her very first trip.

For the first time, trailer trucks could be carried to the Vineyard, each one packed with food enough to stock a supermarket, not just a country store. In the first 10 or 15 years of her life, so large was her automobile deck that a Vineyarder or vacationer could book just about any trip he chose, in season or out, no matter how close to sailing time. She opened a gate to the day-tripper, making so many trips each day that it was now possible for the visitor living almost anywhere in southeastern New England to travel to and from the Island between sunrise and sundown.

With the Islander, the pace of everything quickened, the size of everything grew, the binding together of Island and mainland tightened as it had not tightened since the first steamer, the Marco Bozzaris, began sailing regularly into Edgartown in 1830. The Islander did not create these latest, greatest changes. But she made them possible. In every way, she met the demand.

She also made plain the fact that steamer service from faraway ports was over and done with.

New Bedford was three times farther away from Martha’s Vineyard than Woods Hole, and travelers could tell the difference. In the first 20 days of October 1953, for example, the Authority carried just 13 cars and 237 people from New Bedford to the Vineyard and Nantucket. To remain competitive with Woods Hole, the city insisted on year-round service and that the price of a ticket from either port be the same. The governor, hungry for votes, agreed. The cost to run an aging, overstaffed and undersized fleet of steamboats the additional 16 miles to New Bedford caused the annual deficit to soar monstrously, reaching $614,000 in in 1957 and $620,000 in 1958. That amounted to the cost of building a new ferry Islander each year. It equaled the annual combined budgets of the police and health departments of the town of Tisbury, plus more than half the budget of its highway department. And the Islands were obligated to pay 70 per cent of those deficits.

It took a strike of 77 days in the spring and summer of 1960 to destroy the featherbedding of the Authority steamers and to unshackle the Islands from the burdens of New Bedford service. But with the abandonment of New Bedford went something else, too - the old idea that a trip to Martha’s Vineyard was a real voyage, that this was an Island in spirit and destination as well as in fact.

“There is a special circumstance about going to an Island which cannot fail to have its effect upon a person who inhabits a continent,” wrote Henry Beetle Hough, late editor of the Vineyard Gazette, in his masterpiece Martha’s Vineyard Summer Resort. “As the steamboat crosses Vineyard Sound, and the dark green woods, the white lighthouse, the gleaming beach sands and the buff cliffs at West Chop Ñ as these things seem to rise above the water and grow nearer, there is an inner disturbance in the beholder. His heart is leaping up.”

This sort of thing can happen aboard the crowded uppermost deck of the motor vessel Martha’s Vineyard in the summer of 1999, but it is harder. And ironically enough, the easier our ferries have made travel to and from the Island in this century, the more difficult it has become to book a reservation.

Comments