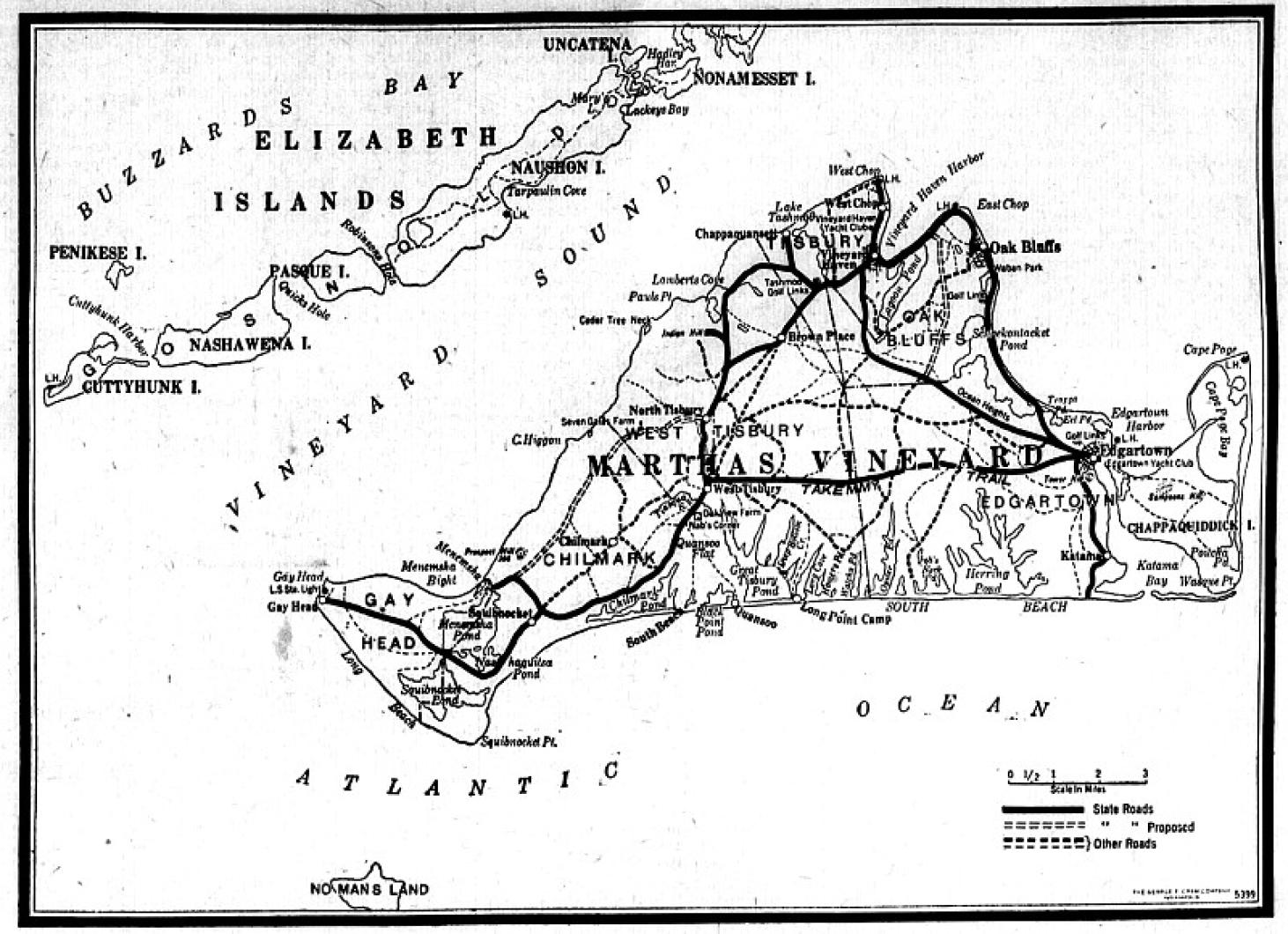

South Road, the main artery of travel between eastern and western extremities of the Vineyard is at once outstanding in its natural scenery and its historical associations. Beginning, properly, opposite Parsonage Pond in West Tisbury village, it extends through Chilmark and Gay Head to the lighthouse and the country park on the headland in that town, where thousands go each year to view the famous Gay Head cliffs. South Road is as ancient a way as any on the Island, if its Wampanoag history be considered, for its original layout constituted the commonly used path between the Gay Head village and Edgartown. Originally it followed the pond and ocean shores for a great distance, but use by white settlers and their wheeled vehicles has brought about the change in its course.

Records show that the beginning of South Road occurred in 1699, when the Mill Path, now known as the West Tisbury-Edgartown Road, was continued to the Chilmark Line, and called the School-house Path. West Tisbury was at that time a growing settlement, and, in that period, was laying out paths in various directions to facilitate travel to various parts of the Island. Aside from the convenience of providing a way to the schoolhouse, the settlers also had their eyes on the brook that crosses the road near the town line, and it was at about this time that the first grist mill was built there by Capt. Benjamin Church, hero of King Philip’s War. The original dam still stands and the pond has supplied water to a grist mill for centuries.

By the roadside near this brook is a stately white house of colonial design, where, according to tradition, stores of gunpowder were concealed at the time of Grey’s Raid in the Revolution. A short distance back, in the village, may be seen Agricultural Hall, a plain structure, but a monument to the memory of Prof. Henry L. Whiting, whose interest in the promotion of Vineyard agriculture inspired him to organize the Dukes County Agricultural Society nearly a century ago. Still flourishing despite failing interest in farms and stock-raising, an annual fair is held there each year and a flourishing grange, named for the town, occupies it regularly in winter.

The heavy pine floor of the upper hall trembled beneath the feet of drilling soldiers during the Civil War, and, until a few years ago, the racks of their guns were still to be seen in a small room equipped for the storage of accoutrements.

Across the grounds, surrounded by one of the first concrete walks ever laid on the Island, stands the school, a three storied structure with mansard roof. Used now as the town school, it was once Mitchell Academy, a private school for boys, a successful enterprise which brought to the Vineyard many families who became permanent or summer residents in later years.

Leaving West Tisbury, and progressing across the line into Chilmark, Oakview Dairy Farm attracts the eye. Reclaimed, for the most part, from wild pasture lands, this farm has won the approval of the state agricultural authorities for many years, and presents an example of what can be done with Vineyard soil and climate.

But a short distance west stand two fine old colonial mansions, one on either side of the highway. Two stories in height, with attics above, they stand foursquare with the compass and gaze out of their tiny windowpanes upon the changes that two centuries have brought since their erection. These are the Adams and Mayhew homesteads, both homes of early religious leaders of the Island. Huge fireplaces, hand-hewn beams and hand made panels and trimmings give the interiors that ancient atmosphere that generations of owners have carefully preserved as family relics, for the properties have never passed out of the original families.

Stone walls, as old as, or possibly even older than the houses, surround the lawns and outlying fields, still standing ruggedly against the onslaught of the elements and the passage of time. Moss-covered and old, the stones lie wedged exactly as the farmers of the hamlet laid them two centuries ago.

Another old house, on the north side of the road, invites attention, also the vacant lot adjoining, where a huge lilac tree and split stone gate-post reveal the former site of a dwelling. The old house is not particularly remarkable save for the fact that it belongs to that period when men built according to means or material, starting pretentiously and ending at times with an abruptness that leaves a half-completed appearance. In this case, the lofty front, with many windows, would indicate the regular, “high, double house” of two centuries ago. But the length of the main portion is but about one half that of the ordinary type and is not revealed until a broadside view is obtained.

A word about the owner and occupant of this house is not out of order, for he is the only chantey-man of the clipper ship era left to the Island, and perhaps to the whole of New England. One of the sea-faring Tiltons, a brother of the well known Capt. George Fred Tilton. William S. Tilton has sung his way over all the oceans of the globe and in and out of all principal sea-ports as well as along barren and savage coasts.

The vacant lot with its forlorn gate posts standing guard over the memories of the past, is the site of an Indian trading post which existed when the frontier of the Island extended across those hills. A crumbling foundation and a brush-grown cellar indicate the spot where the house stood, a house that was at once a store and an inn, for the travellers of 1720 stopped here on their journeys up and down the Island. Over the high hills, not far away, lie scores of the Indians who used to bring their pelts and fish to trade for goods at this post, their graves marked by rough field stones set on end, while the public library of West Tisbury, may be seen the ledger in which is set down entries of lumber for coffins and sheets for burial, indicating the Christian practices of these men of the time.

The entrance of the Methodist Cross Road is next encoutered, a narrow, winding road of dirt, that crosses one of the high ranges of Island hills, connecting with Middle Road. It is passable and pleasant for cars, but there is little to be seen save a fine view of Vineyard Sound from the most loft y point, and a portion of Old King’s Highway where it crosses, on the southern slope of the ridge. There are but few worshippers to travel this road today, and the church no longer stands at its end, as formerly.

The principal landmark of South Road now rears its head, Abel’s Hill, the lofty eminence overlooking miles of land and sea. Named for the Wampanoag who once owned the land, this hill has been used as a bearing and landmark ever since the Island was occupied by the whites, and, without doubt, long before.

Across the crest passed the ancient Indian trail which developed eventually into South Road. At the southern foot, lies Chilmark Pond, blue and rippling, while across the narrow stretch of yellow dunes lies the broad Atlantic Ocean, with the nearest land in a easterly direction, the coast of Spain.

Here the Wampanoags came to fish and gather shellfish. Quansoo is revealed, and portions of West Tisbury Pond to the east, concealed before by woods, but now showing clearly. Another historic spot, the home of the early Hancocks, ancestors of the famous signer and still held by descendants of the family. This place, too, is reached only from South Road, the drive leaving the highway near the Adams’ Homestead. Its Indian name endures, “Quansoo,” meaning eel, or “long fish,” indicative of the principal product of the pond.

From Abel’s Hill, Noman’s Land, shows clearly across from the sand cliffs of Squibnocket, Noman’s Land, the mysteriously abandoned island found by the first explorers, visited perhaps by early Norsemen and certainly by Wanpanoags who left many relics behind.

From this hill, the lookouts of Colonial days watched for whales, reporting to the “shore-whalemen” who were farmers and fishermen in ordinary times. Many of these men sleep in the cemetery on the opposite side of the road from the sea, a short distance nearer the water than the Wampanoags who taught them to fish and catch whales.

The old road swung nearer to the water than the present one, so close that a part of it crossed marshy ground. A mail-carrier of several generations ago, riding his horse along this trail, was thrown when the animal plunged into the mud. In assisting the horse to extricate itself, the rider saw the glint of gold coins, and, investigating, discovered a pot or chest of money. There is nothing mythical about this story, although the exact spot where the money was found may not be known to anyone today.

More old houses, very old indeed, then a tiny trickle of water that still bears the name of Fulling-mill Brook, though one wonders how a sufficient flow of water was ever obtained to operate even the lightest of machinery.

Chilmark village, with its store, post office and town hall. The town hall, besides serving its civic purpose, is also the headquarters of Chilmark Grange. Here is a tiny civic center as in West Tisbury, but with a high rolling country beckoning. Up on this slope stands the old Great House, famed for its age and the tale of more powder concealed there during the Revolutionary raids. A young woman rolled a keg of the precious ammunition into a corner of the huge fireplace and sat there upon it, knitting, though the fire crackled at her feet, and all the while, British marines ransacked the place.

Harry’s Creek Bridge forms a link that makes Gay Head a peninsula instead of an island. It is a picturesque spot, with Menemsha Pond on the north, and Quitsa Pond on the south. Shelldrakes, loons and other wild fowl are often seen there during the nesting season.

The estate of Alice Stone Blackwell, internationally known supporter of woman suffrage. A lovely grave in a meadow, with old stones of English slate marking it. The grave of a young seaman, stricken with small-pox as he neared his home, dying before he could be carried from boat to the house. Fearful of the disease, residents buried him where he died and a century and more has passed since then, but the legend, in part, may be easily read upon the stone.

A wonderful hilltop view of Menemsha Pond and the fishing village of Menemsha Creek in the distance. Prospect Hill, far to the east, Peaked Hill, slightly nearer, Powwow Hill on the left and Vineyard Sound in the distance.

Only a short distance from this hill stands the cromlech of Quitsa, for Quitsa is the name of this location. The cromlech undoubtedly marks the burial place of a Norse explorer. Scientific men have viewed the monument, at various times, and none has yet been found who disputes this theory. It is believed to be the only relic of its kind in America and is generally accepted as positive proof of Norse occupancy of the Vineyard at some long-forgotten time. Standing on private property, it is not accessible to the public, but various students and interested persons have been granted permission to view the monument and take photographs.

The town herring creek passes under the highway, with a noble colonial-built house falling to decay beside it. A story book place, if there ever was one, and popularly believed to be haunted by the shade of a piratical gentleman of olden times who lived there and who was poisoned by maiden who sought his love in vain.

A short distance from this place, the highway departs from the old, original track, but the ancient road may still be seen and followed, on foot.

On the main road, lies the scattered village of Gay Head. Small but tidy houses, owned and occupied by men and women of Wampanoag descent. Nearly all of the original male residents of middle age, have been coastguardsmen or volunteer life savers, and in these families, there are many treasured medals awarded for bravery and fortitude.

By the side of this road stands the grave of Silas Paul, Indian preacher, marked with a field stone bearing an inscription of the Indian language, the only such stone on the Island. Past it roll the ox-carts, still employed by the little farms. There are other cattle in the fields, which are principally owned in common, like the wild, natural cranberry bogs which yield a harvest each year with no attention or care. And it is a singular fact that there is scarcely any hay harvested on Gay Head, the wild hay supplying the cattle with adequate grazing throughout the year. Even the winter snows fail to hinder the grazing, for the salty air quickly melts what little remains on this high promontory.

Gay Head lighthouse and Coast Guard station, immaculate, efficient and kept by men who welcome the sight-seer. The cliffs, 200 feet in height, mottled with brightly-colored clays that present a bewildering riot of tints to the onlooker. Noman’s Land, looming nearer, the sand dunes of Squibnocket, and Southwest Head, Menemsha Bight, with fishing boats sailing past. The Elizabeth Islands, showing so clearly that the houses can be distinguished across five miles of sea. And everywhere, old landmarks, Indian cemeteries, the sites of wigwams, cairns and tribal gathering places which can be visited if the seeker is willing to secure the services of a guide.

The road loops around the park, and turns back upon itself, for there is only one road to Gay Head. But one trip over it is seldom sufficient to satisfy the interest of the visitor. It must be travelled many times.

Comments