The town of Gay Head signed the deed conveying the ancestral Wampanoag Indian Common Lands to the federal government yesterday, ending a protracted legal struggle for the tribe with quiet agreement.

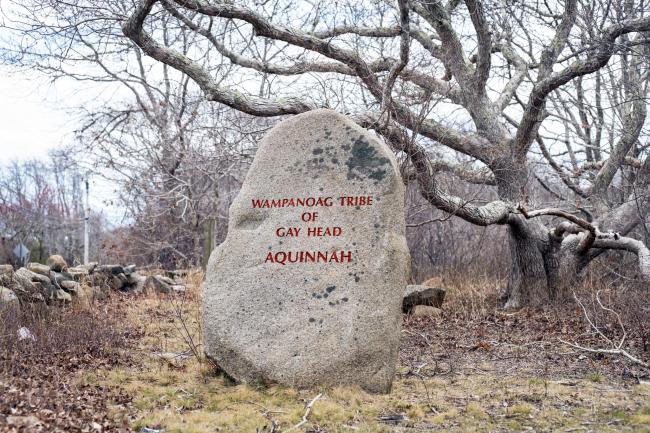

The face of the Gay Head Cliffs, the Herring Creek and the cranberry bogs will be under the control of the Wampanoag Tribal Council of Gay Head Inc. as the representative of the Gay Head Wampanoag Tribe.

The federal government will actually hold title to the property, but control of the land will pass to the tribal council in the form of declaration of trust.

Present at the signing in the offices of Reynolds, Rappaport and Kaplan were town counsel Ronald Rappaport, selectmen Jeffery L. Madison, David E. Vanderhoop, and Walter E. Delaney, and town clerk Evelyn C. Vanderhoop. Donald Widdiss, tribal council president, also attended.

Mr. Rappaport made adjustments to the language in the deed up to one hour before the signing ceremony on Thursday afternoon. He explained the minor adjustments in the deed language, and then asked the selectmen if they had any questions.

There was a moment of silence. Mr. Rappaport asked if the selectmen were prepared to sign.

“I’m ready,” said Mr. Madison.

The others added their acknowledgment. The signature page was passed to Mr. Vanderhoop, Mr. Delaney and then Mr. Madison.

Mrs. Vanderhoop added her signature and affixed the town seal. The document was notarized.

There were handshakes and there was laughter.

“Now about the rest of the Island,” Mr. Widdiss said to Mr. Rappaport with mock seriousness.

The deed will now be forwarded to Lewis M. Baylor, an attorney with the U.S. Department of Justice. He will act as legal agent for the federal government and prepare an acceptance document, which will be returned to Edgartown with the deed and filed in the Dukes County Registry of Deeds.

“The bureaucratic road had been long and trying,” said Mr. Vanderhoop.

“Like the road to Gay Head a hundred years ago,” added Mrs. Vanderhoop.

That road has taken many unexpected turns. The land suit began in 1974 when the Wampanoag Indians of Gay Head, at that time without tribal status from the U.S. government, sued to reclaim the Gay Head Common Lands.

These lands were held in common by all Wampanoag tribal members as part of their tradition and culture. In 1870 the General Court of Massachusetts enacted legislation changing the Gay Head Wampanoag lands into the town of Gay Head. Lots were surveyed and deeded to individual tribal members, and the so-called Common Lands - the face of the spectacular clay cliffs, the cranberry bogs, and the Herring Creek - passed on to the newly incorporated town of Gay Head. The Native American Rights Fund in Washington D.C. sued on behalf of the Wampanoag Tribe to reclaim those traditional holdings 104 years later.

The town of Gay Head voted to empower their selectmen to negotiate a settlement with the tribal council in 1976, and by the end of the year voters approved the transfer of the Common Lands to the tribal council. Within a week the Gay Head Taxpayers Association filed papers with a federal judge arguing that the Gay Head selectmen did not represent the interests of non-Indian voters of Gay Head. The taxpayers became a negotiating party for the next 13 years.

In 1977 the tribal council voted to add additional lands to the suit. Various land claims on Chappaquiddick, in Chilmark, Christiantown and Deep Bottom were discussed in the subsequent months. In the spring, direct negotiations with the taxpayers association appeared imminent, then rumors that the tribe was maneuvering to gain fishing rights to all of Menemsha Pond and other lands heightened the battles inside tribal membership, the tribal council, Chilmark residents and members of the taxpayers association. Harvard Law School Dean Albert M. Sachs was appointed mediator.

A similar land claim suit pursued by the Wampanoags in Mashpee on Cape Cod was defeated in federal court the following spring. The judge ruled that the Mashpee Wampanoags had not acted as a tribe when the town of Mashpee was incorporated. The decision, which drew on the 1790 Indian Non-Intercourse Act, set a precedent which affected criteria for all subsequent tribal recognition cases before the federal government.

By November of 1978 it was reported a settlement was near. The proposed settlement package named the 238 acres of Common Lands, three lots held by the bankrupt Strock Corporation, and the Cook property adjacent to the Herring Creek. But by April of the following year, the agreement fell apart, with charges of negotiating in bad faith from all sides.

In December 1980 the Gay Head selectmen petitioned the federal court to set a trial date for the land claim suit and one week later the tribal council released a new settlement proposal. The proposal included the 238 acres of Common Lands, 175 acres of the private Strock holdings, and a guarantee the tribal council would drop any other land claims. The taxpayers association reacted strongly against the Wampanoags’ bid to include the beach adjacent to the cranberry bogs in their land claim. For the next eight years beach access was a key point of debate between the taxpayers and the tribe.

In July 1981 the state attorney general entered the suit, just as the tribal council petitioned the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs for tribal recognition.

The following month a dissident group of 43 tribal members filed suit to increase land claims to include the whole town of Gay Head. Divisions within the tribe were widening, and by the end of 1981 a series of suits were filed for a diverse group of Wampanoags by the Massachusetts Indian Heritage Committee claiming land in Gay Head, West Tisbury, Edgartown, Plymouth, Borne, Fall River and Mashpee.

In July 1982 a federal judge in Boston dismissed an appeal to the earlier Mashpee land claim, effectively shutting down the heritage suit and making documentation of continuous tribal existence a criteria for Indian land claims.

By 1983 the BIA placed the Gay Head request under active consideration with a one-year deadline. Three months later that request was removed from active consideration as part of the settlement agreement with the taxpayers association, which was signed bu all partied in December of that year.

The settlement agreement was the first in a succession of important steps that ended in federal recognition, the acquisition of the Strock properties, and the transfer of the Common Lands. By the end of 1984 a superior court judge barred the dissident tribal faction from any further land claims.

The state legislation was passed by the following summer, but passage of the federal legislation became bogged down when the BIA questioned the Gay Head Wampanoags on their legal status as a tribe.

The petition for federal recognition was again placed under active consideration in June 1985 and was formally opposed by the taxpayers, who argued that the request for federal recognition was a breach of the settlement agreement.

The request for recognition was denied by the BIA in a preliminary hearing before a U.S. Congressional Committee in Washington, D.C. in June 1986, convincing many that the tribe’s prospects were bleak. The Gay Head Wampanoags met five of the seven criteria for tribal status. The government decision said the tribe could not prove that they have lived in a distinctly American Indian community in which a substantial number of Wampanoags maintain tribal ties. The government also argued that the Wampanoags failed to prove that they maintained some form of tribal government continuously. The tribal council appealed this decision.

The federal government recognized the tribal status of the Gay Head Wampanoag Indians in February 1987 in an unprecedented finding. Congress passed the land claims settlement legislation and President Reagan signed it into law that August.

The tribe purchased the Strock property to be used for affordable housing for tribal members in February 1988 and the final transfer of the Common Lands was expected to follow quickly, but problems with the settlement agreement stalled that transfer. The taxpayers association wanted a guarantee that access to Lobsterville Beach would be maintained.

A memorandum of clarification was drawn up in May 1989 to address problems associated with maintaining town control of Lobsterville Beach. The taxpayers pushed for beach parking, but negotiations stalled.

Then Henry Sockbeson, the Native American Rights Fund attorney representing the tribal council, began to investigate the possibility of going ahead with the land transfer without the taxpayers association, which is not considered a legal party in the deed transfer. The settlement agreement was signed and valid, and the town was able to transfer the deed to the federal government, he argued. Yesterday the town did just that.

Comments